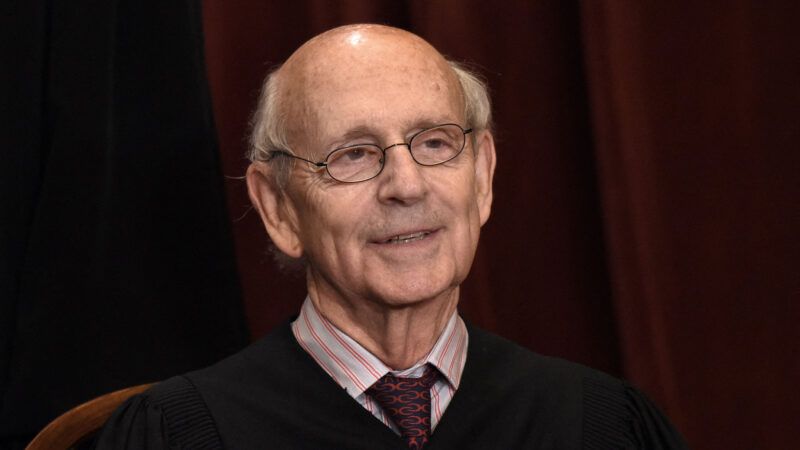

Stephen Breyer's Retirement Is Good News for the Fourth Amendment

Breyer’s deference to law enforcement often led him to sell the Fourth Amendment short.

When President Bill Clinton tapped Stephen Breyer to fill a vacancy on the U.S. Supreme Court in 1994, he told the country that Breyer would be a justice who would "strike the right balance between the need for discipline and order, being firm on law enforcement issues but really sticking in there for the Bill of Rights."

The news of Breyer's impending retirement at the close of the Supreme Court's current term gives us an opportunity to weigh Clinton's words against Breyer's record. Alas, the former president proved to be only half right. Breyer was certainly "firm" in his deference toward law enforcement. But that same judicial deference often led Breyer to do the opposite of "sticking in there for the Bill of Rights" when major Fourth Amendment cases arrived at SCOTUS.

Take Navarette v. California (2014). At issue was an anonymous and uncorroborated 911 phone call about an allegedly dangerous driver which led the police to make a traffic stop that led to a drug bust. According to the 5–4 majority opinion of Justice Clarence Thomas, "the stop complied with the Fourth Amendment because, under the totality of the circumstances, the officer had reasonable suspicion that the driver was intoxicated." Law enforcement won big and Breyer signed on.

The deficiencies of that judgment were spelled out in a forceful dissent by Justice Antonin Scalia. "The Court's opinion serves up a freedom-destroying cocktail," wrote Scalia, who was joined in dissent by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan. "All the malevolent 911 caller need do is assert a traffic violation, and the targeted car will be stopped, forcibly if necessary, by the police." That disturbing scenario, Scalia wrote, "is not my concept, and I am sure it would not be the Framers', of a people secure from unreasonable searches and seizures." Breyer was apparently untroubled by that Fourth Amendment–shredding scenario.

Notably, this was not the first time that Scalia was more "liberal" than Breyer in a 5–4 Fourth Amendment case. One year earlier, in Maryland v. King (2013), Breyer joined Justice Anthony Kennedy's controversial majority opinion allowing police to conduct warrantless DNA swab tests incident to arrest.

"Make no mistake about it," Scalia protested in dissent, joined (again) by Ginsburg, Sotomayor, and Kagan. "As an entirely predictable consequence of today's decision, your DNA can be taken and entered into a national DNA database if you are ever arrested, rightly or wrongly, and for whatever reason." Breyer was apparently untroubled by that disturbing scenario too.

Breyer's retirement will be good news for the Fourth Amendment as long as President Joe Biden picks a replacement who resembles Scalia more than Breyer in these sorts of cases.

Show Comments (148)