40 Years of Trillion-Dollar Debt

Forty years from now, it'll be much, much, much higher.

On October 22, 1981—exactly 40 years ago today—America's national debt hit $1 trillion for the first time.

"If we, as a nation, need a warning," President Ronald Reagan said in a televised address a few weeks before the country surpassed the 13-figure debt threshold, "let that be it."

Today, the national debt exceeds $28 trillion. In the fiscal year that concluded at the end of last month, the country added another $2.77 trillion to the pile, the Treasury Department announced just this morning. The Congressional Budget Office anticipates that the country will add at least another $1 trillion to the deficit for just about every year in the foreseeable future—and that's even without any new spending.

If a trillion-dollar debt was a warning sign, it was ignored.

The Washington Post's contemporaneous coverage of the symbolic 1981 milestone is now a quaint window into a strange world. The paper reported that the country surpassed $1 billion in debt during the Civil War and then $500 billion in the mid-1970s. "In other words, half of the current trillion-dollar debt was incurred in the last seven years," the Post noted.

Shocking, right? Now, we run up half-trillion-dollar debts every few months.

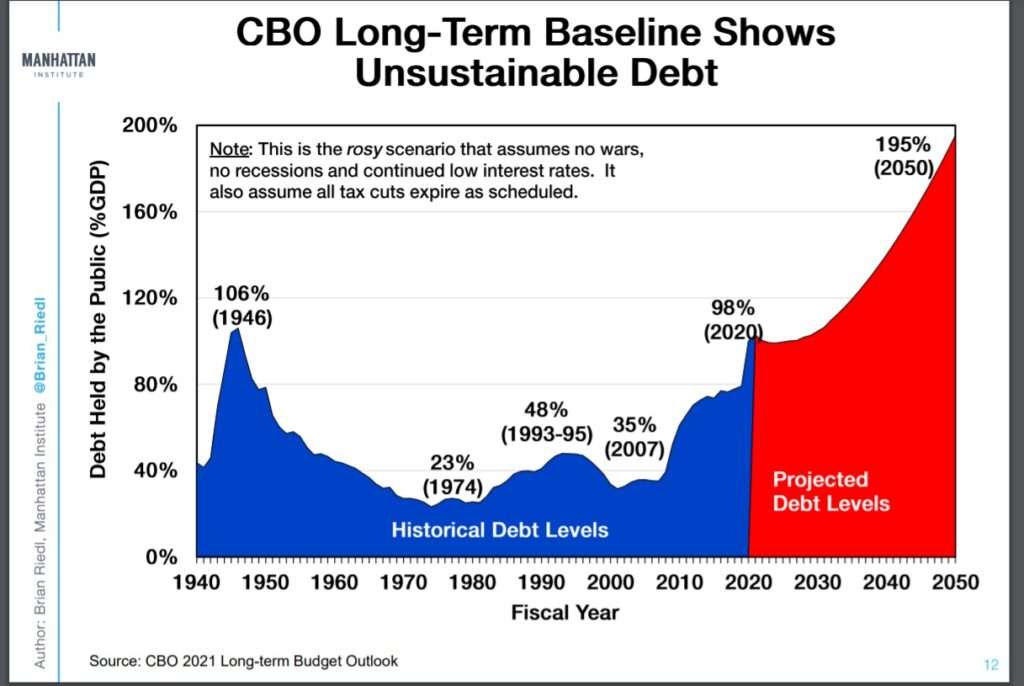

It's true, of course, that $1 trillion doesn't buy what it used to. That amount in 1981 would purchase about $3 trillion worth of stuff today. The best way to measure the national debt over long periods of time is to compare it to America's gross domestic product (GDP), a rough estimate of the size of the country's economy in a given year.

In the early 1980s, for example, even as the gross national debt exceeded $1 trillion for the first time, the national debt was less than 40 percent of GDP. The national debt is now equivalent to the country's GDP and is on pace to be nearly 200 percent of GDP by the middle of the century, as this chart from Brian Riedl, a deficit hawk and former Republican Senate staffer now working at the Manhattan Institute, helpfully illustrates:

Another useful way to measure the growing national debt is to look at how much it would cost the average American household to pay it off. Again, the trend in recent decades is not a good one.

Rising costs of entitlement programs and the interest on the debt itself are the primary reasons why the debt will keep growing. In other words, even cutting a lot of discretionary spending would have little effect on the debt at this point.

The guilty parties are, well, both parties. It was fitting that the debt hit the symbolic $1 trillion figure during Reagan's presidency, as the Gipper ignored his own warning. Republicans have spent much of the past 40 years venerating Reagan as an icon of conservative values, including supposedly limited government. And while his successors ran up far larger amounts on the nation's credit card, Reagan saw the government surpass not only the $1 trillion debt threshold but also the $2 trillion threshold.

Meanwhile, few Democrats today agree with President Bill Clinton's admonition that "we have got to deal with this big, long-term debt problem, or it will deal with us."

"It will gobble up a bigger and bigger percentage of the federal budget we'd rather spend on education and health care and science and technology," Clinton, the last president to reduce the size of the national debt over a single fiscal year, warned at the 2012 Democratic National Convention.

The guiding principle for today's Democratic Party is the idea that debt doesn't really matter if interest rates remain low. So long as the cost of servicing the federal debt stays below 2 percent, policymakers should not be restrained by the "traditional idea of a cyclically balanced budget," Larry Summers, Clinton's treasury secretary, and former Obama economic adviser Jason Furman argued in an influential paper published last year.

But the past 40 years would suggest that lawmakers have almost never been restrained by the idea of balanced budgets—a few brief interludes of fiscal sanity notwithstanding.

It took nearly two centuries for America to accumulate $1 trillion in public debt. It took 40 years to increase that amount 28 times over. If we refuse to address the breakneck speed at which America spends money it doesn't have, how long until Clinton's warning is realized, and that debt deals with us?

Show Comments (127)