Excessive Bureaucracy Is Making America's Broken Immigration System Worse

A new Government Accountability Office report offers a useful lesson about the often unseen, human costs of making forms more difficult to fill out.

The chaos unfolding at the Del Rio International Bridge in Texas might be getting all the headlines, but arguably a bigger problem with America's broken immigration system has to do with a far less exciting topic: paperwork.

There is a lot of it. And, thanks to one of the lingering effects of the Trump administration, there is even more paperwork required to immigrate legally today than there used to be.

Yes, the Trump administration had a mixed-to-good track record when it came to deregulating various aspects of the federal government. But the opposite was true when it came to immigration policy. By demanding more information from would-be immigrants and mandating that immigration officials conduct in-person interviews before approving applications, the previous administration created new administrative burdens.

A recent report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) spells out some of the consequences of Trump's efforts to slow legal immigration by tangling it in additional layers of bureaucratic red tape. Among other things, the GAO says that one of the major drivers of the immigration system's mounting caseloads—The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) reports a backlog of nearly 7 million applications and petitions—is the government's own, recently beefed-up immigration bureaucracy.

"Policy changes resulting in increases in the length of USCIS forms and expanded interview requirements" are one of the main reason's why the USCIS' pending caseload has expanded by 85 percent since 2015, even as the number of applications and petitions remained relatively flat, the GAO reported last month. "Longer forms increased the amount of time it takes for staff to adjudicate applications and petitions, and resulted in longer interviews, since adjudicators were to collect and confirm additional information."

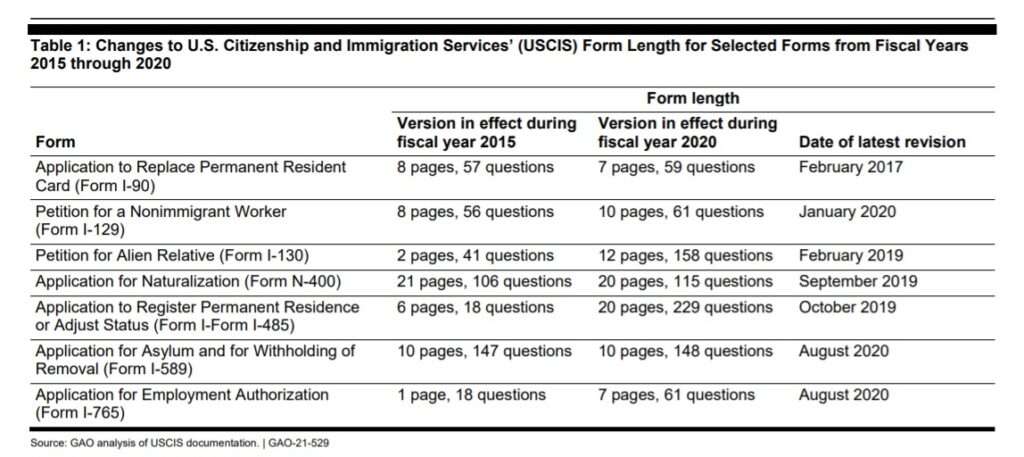

The GAO's review looked at seven of the most frequently used immigration forms and petitions—forms that account for roughly 70 percent of USCIS' pending caseload—and found that six of them had increased in length since 2015. In some cases, the increases were dramatic. The Application for Employment Authorization was expanded from one page and 18 questions to seven pages and 61 questions. Form I-130, which is the first step in applying to have a relative immigrate legally, went from being two pages and 41 questions to 12 pages and 158 questions.

As you'd expect, the processing time for Form I-130 increased as well—from an average of about three months in 2015 to more than 11 months last year, the GAO found.

This is perhaps an underappreciated aspect of how the Trump administration sought to limit legal immigration—one that the Biden administration has so far done little to reverse. We're now seeing the consequences of what some immigration experts warned at the time were "small but well-calibrated actions through regulations, administrative guidelines, and immigration application processing changes" intended to slow down "family- and employment-based immigration" as well as refugee admissions and other forms of legal entry into the country.

And all that was before Trump shut down the county's immigration offices in March 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic hit—a move that added to the backlogs and one that Biden has yet to fully undo.

There may not be a direct line between those actions and the migrants seeking to enter the country at the Del Rio bridge this week. But there are undoubtedly some spill-over effects. Some migrants with relatives in the United States likely would have taken advantage of the legal immigration system if it were functioning more smoothly, or at all. Obviously, there should be better alternatives for people who want to come to America to peacefully work than to pile up under a bridge and hope to avoid deportation.

Unlike the current situation at the border—which is largely the result of migrants fleeing horrible conditions in Haiti and El Salvador—the problems plaguing the legal immigration system are mostly self-imposed and thus within the power of the Biden administration to solve.

It could start by rolling up some red tape. Until Congress or the Biden administration gets around to fixing this mess, the legal immigration backlog is a useful reminder about the often unseen, human costs of expansive government bureaucracy—and how that bureaucracy can be weaponized for political ends just by making forms more difficult to fill out.

Show Comments (62)