Adding Human Gene Boosts Crop Yields by 50 Percent

The technique "could potentially help address problems of poverty and food insecurity at a global scale."

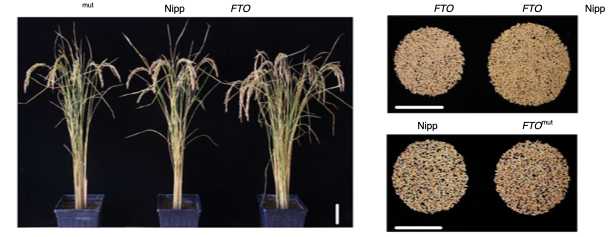

Adding the human gene that produces the FTO enzyme to rice and potatoes boosts yields of those crops by 50 percent in field tests, report a team of researchers associated with the University of Chicago, Peking University, and Guizhou University. Their report in the journal Nature Biotechnology says the modified plants grew significantly larger, produced longer root systems, and were better able to tolerate drought stress. In humans, the FTO enzyme erases certain markers that regulate the production of proteins associated with cellular growth. In plants, the FTO enzyme similarly erases markers that inhibit their growth.

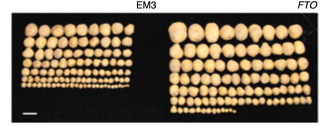

"The rice plants grew three times more rice under laboratory conditions," reports the accompanying press release. "When [the researchers] tried it out in real field tests, the plants grew 50% more mass and yielded 50% more rice. They grew longer roots, photosynthesized more efficiently, and could better withstand stress from drought." The researchers also inserted the FTO gene into potatoes and the results were the same—yields in the field increased by 50 percent. Modified rice produced more grains per stalk; the number of potatoes didn't increase, but their weights did. The researchers reported that neither rice nor potatoes showed significant changes in their starch, protein, total carbohydrate, or vitamin C content. They believe that the technique is universal and would boost the productivity and drought tolerance of not only most crops, but also trees, grasses, and more.

The researchers also think that this discovery will lead to finding out how to boost yields by modifying the plants' own genes that inhibit growth.

"This is a very exciting technology and could potentially help address problems of poverty and food insecurity at a global scale—and could also potentially be useful in responding to climate change," said University of Chicago Economics Nobelist Michael Kremer in the press release.

Show Comments (158)