He Sold $20 Worth of Drugs. Prosecutors Want Him in Jail for Almost 10 Years—and More if He Refuses the Plea Deal.

That's illegal, says a new lawsuit.

Michael Calhoun is a 61-year-old man who is facing almost a decade behind bars. Over the course of his life, he has never been arrested on any violent charge. His offense: He sold about $20 worth of drugs.

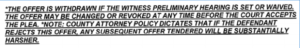

Yet to be caged for those nine years and change is a privilege, says the Maricopa County Attorney's Office (MCAO), which offered Calhoun that sentence in the form of a plea deal. Should he exercise his legal right to a trial, it has threatened him with a "substantially harsher" punishment—a tactic used to bully alleged offenders into giving up their shot at justice.

That's illegal, says a new lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) against Allister Adel, the Maricopa County Attorney.

Calhoun, a plaintiff living in Phoenix, was referred to the Early Disposition Court (EDC), a subset of the judiciary designed to help expedite low-level offenders off the docket. Established in the late 1990s, it is supposed to be an "innovative approach in processing cases to alleviate the backlog of trials in the Criminal Division and to respond to the community's desire to offer treatment to drug offenders," according to the local government. [Emphasis mine.]

Maricopa County offers them a whole lot more than treatment, says the suit, pushing stratospheric prison terms on suspects without a preliminary hearing and without the alleged offender having the chance to review the evidence against them. Calhoun's deal, and related deals, are accompanied by a warning:

For anyone who has had the displeasure of watching today's onslaught of true crime television shows, the tactic probably doesn't land as a surprise. But the MCAO, in being more brazen than most local governments, has laid bare the potential illegality of the approach, which amounts to blackmailing people into giving up their constitutional rights at no benefit to the community. If prosecutors believed Calhoun needed to spend more time behind bars to protect society, then they would have pursued that at the outset. But that's not what's going on here.

"The Constitution provides that everybody has a right to a jury trial in any criminal prosecution," says Clark Neily, senior vice president for legal studies at the Cato Institute. "For the government, this is a problem, because a prosecution that culminates in a trial is expensive and inconvenient and uncertain….The ability to induce a defendant to waive the right to a trial is a very attractive option, both because it saves money and time, but because it eliminates the uncertainty of a jury trial."

The result: Prosecutors start by offering a prison term that's already disproportionately high—often piling on multiple charges for the same offense—effectively pressuring people into acquiescence at the fear of receiving a sentence even more grotesque. People like Calhoun thus end up staring down years upon years in prison for victimless crimes—something that Maricopa County itself acknowledges should be "diverted into a drug treatment program." The ACLU suit notes that, according to records obtained from Maricopa County Court in October of 2018, only 8 percent of cases were diverted.

Also a plaintiff in the suit is Levonta Barker, a man who was charged with two counts each of aggravated assault and kidnapping and offered seven and a half years in prison. The problem: He was innocent, and was given that plea deal before MCAO bothered to do any investigation, much less before allowing Barker to attend a probable cause hearing or parse through the evidence with his attorney. His lawyer ultimately pointed out that when Barker was arrested, he was wearing a different outfit from the one the perpetrator was described as wearing in police reports. The MCAO had not verified those basics, and Barker spent a month in jail because of it.

Jury trials are indeed expensive affairs, sometimes climbing up into six figures. Plea deals are thus seen as a cost-saver. Apply that logic in reverse, and the government would only pursue trials for the offenders it actually thinks pose a real threat to the community. By its own admission, Calhoun wouldn't qualify.

It might also help remind the government what is and is not worth its time. In October 2019, New Orleans prosecutors sought to impanel a jury to consider a felony marijuana charge. They couldn't find six people who would even indulge them. As it stands today, maybe Maricopa County could find those jurors. Perhaps it won't always be that way.

Show Comments (60)