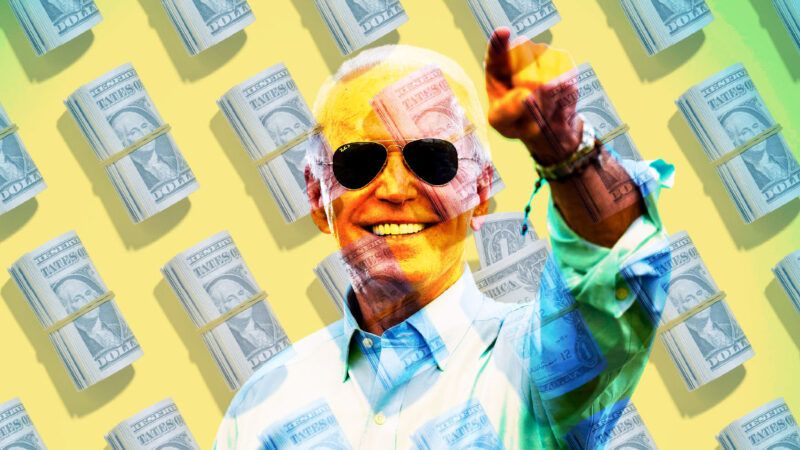

The Bill Will Come Due on Biden's Trillions

Biden's infrastructure package is really a jackpot for public unions and big business.

You know we have crossed a fiscal Rubicon when a presidential administration does not attempt to justify its spending, instead simply claiming that because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Americans must now welcome with joy and gratitude any spending bill, no matter how big, frivolous, or cronyist.

Based on that belief, President Joe Biden first backed a $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief bill that could not be justified by any broadly accepted economic theory. He then announced a $2.3 trillion "infrastructure" package that he described as a "once-in-a-generation investment in America unlike anything we've done since we built the interstate highway system and the space race decades ago."

A closer look reveals that the plan is instead a jackpot for public unions and big business. Coming after two decades of spending indulgence under the last three presidents, culminating in an explosion of outlays during Washington's COVID-fighting efforts, Biden's spending extravaganza is in effect the final stage of an effort to centralize power in the federal government, which will fund ever more private, state, and local government -functions.

Gesturing toward fiscal responsibility, Biden plans to pay for most of his latest plan with a $2 trillion increase in corporate taxes, arguably the largest hike since World War II. The combined tax hikes, according to the Tax Foundation, likely will reduce private infrastructure investment by $1 trillion. A corporate tax increase from 21 to 28 percent, for instance, would reduce the after-tax rate of return on corporate investment in America and in turn reduce the amount of investment. The hikes will nevertheless please the anti-corporate wing of the Democratic Party. Never mind that the price will be paid by workers whose wages won't grow and small-business owners who will have less access to capital.

The infrastructure bill creates an interesting tension. On one hand, Wall Street will hate these tax increases, the full effect of which will be felt in the next decade and a half. On the other hand, corporate titans probably are banking on their ability to fight these taxes while enjoying Biden's $2 trillion corporate welfare handout today.

How else to explain the stock market upswing after Biden's Pittsburgh speech announcing that trillions more dollars will be spent and taxed by Washington? Could it be that years of Federal Reserve liquidity injections, the promise of rescue, and artificially low interest rates have permanently transformed Wall Street into a corrupt moocher? It is as if corporate America believes the Fed will never let the market correct, guaranteeing growing corporate profits in perpetuity.

But there's a reason we economists always remind people that the stock market isn't the economy and the economy isn't the market. In the short run, the stock market's success tells you little about the soundness of policy decisions made by people in Washington. The reality is that one day, all that debt, cronyism, and lack of accountability will explode in our faces. It might take some time, but when the time draws near, don't assume that interest rates will alert us to the impending disaster or that the Fed can save us without inflicting massive pain.

When we look back and wonder how we got there, we will see that there is a lot of blame to go around. By recklessly monetizing the public debt and suppressing interest rates, the Federal Reserve allowed deficit spending to become the norm. The party of small government, meanwhile, simply gave up the small part. Congressional Republicans remained mostly silent while the Trump administration ran up the public debt by nearly $9 trillion in just four years, slowed down the economy with protective tariffs, and imposed disgusting and costly immigration restrictions. Some Republicans offered their own central planning proposals in the name of fighting China; others endorsed plans for a federal paid leave law and a universal basic income for kids.

On the other side of the aisle, even the Keynesians seem lost in our brave new world. Lawrence Summers—secretary of the treasury in the Clinton administration, director of the National Economic Council in the Obama administration, and president of Harvard in the interregnum—fought a good fight to reduce the size of the $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief bill. He argued that economic theory could not justify the package's size. He lost.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Look, Joe needs a presidential legacy for his obituary. There isn't much time. Harris may have one written up in her desk.

Please, she had that written up before the inauguration.

Over under for cackle breaks is 15.

Making money online more than 15$ just by doing simple work from home. I have received $18376 last month. Its an easy and simple job to do and its earnings are much better than regular office job and even a little child DDS can do this and earns money. Everybody must try this job by just use the info

on this page.....VISIT HERE

Most destructive President in US history. Quite a legacy!

Creepy Joe will likely being taking a dirt shortly so why should he give a fuck about unintended consequences of maxing out the credit card when he won’t be around when the bill comes in?

Paying for it will fall on future generations, like Hunter and his children.

Well, not Hunter specifically.

But the genius of this is that by the time the bill comes due, a trillion dollars will buy you a loaf of bread so the debt can be paid off with a pair of shoes or something.

The party of small government, meanwhile, simply gave up the small part.

Republicans have literally never been the party of small government.

But, but, but....Orange Man was Bad! Right Veronique?

You got what you wished for. Now you bitch about it?

Orange man was bad, that doesn't make his replacement good.

In fact if not for the orange man and his cronies the Senate might have stayed Republican and we'd be looking at a divided government.

Bingo. The choices were reckless spending and even more reckless spending.

Based on that belief, President Joe Biden first backed a $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief bill that could not be justified by any broadly accepted economic theory.

MMT. What do you think Biden meant when he said Milton Friedman wasn't running the show any more? He was channeling Paul Krugman who insisted the government just needed to spend tons of money and it didn't matter how it got spent, pay people to bury the money in holes and pay other people to dig it up, for example. (This right after he got done throwing a shit fit over Bush spending tons of money on the war in Iraq so apparently when he said it didn't matter how the government spent the money he was excepting some sorts of government spending.)

And it makes sense if you assume government spending carries some sort of "multiplier" that private spending doesn't. The GDP of the US is some $20 trillion+, if the government were to take all of that money rather than just a portion of it, government spending would double our GDP at least, depending on the multiplier and we'd all be rich! Government should be in charge of spending all the money to get as much bang for the buck as possible.

And with the death of the "meritocracy" myth, why should the income distribution be what it is, why isn't it just and proper that the government take all the money and redistribute it more equitably and fairly? Why should dishwashers make $25,000 per year while crane operators make $90,000 and heart surgeons make $800,000? Who decided that was fair? Salaries should be based on how much money you need, not on some nebulous idea of how much you contribute to others.

Spending your way to wealth sure makes a convenient rationalization for people who want to spend money, how fortuitous is that?

Gee, thanks for making me want a couple of beers before breakfast.

Thing is Kaufman himself has criticized MMT and identifies as a New Keynesian, which means allegedly he believes deficit spending during a downturn must be balanced by cuts during boom years. But for years now his economic principles have taken a backseat to partisanship.

Argh I meant Krugman

"Salaries should be based on how much money you need, not on some nebulous idea of how much you contribute to others."

I always thought the basic tenets of Communism were pretty naive and unrealistic, but these retards have taken "from each his ability, to each his need" and turned it into "to each xer/xe wildest desires, from those privileged, money-hoarding, one-percenter racists."

“from each his ability, to each his need”

Unsurprising that the party of slavery would adopt this concept.

At least Democrats have returned to their roots: the party of rich white people who know what's best for black people.

I'm not sure I ever heard as much consternation when Trump and the Rs passed their giveaway to the wealthy without any complementary spending cuts.

It's almost as if the writers dutifully ignore things that benefit their master Koch. At least infrastructure would help out someone.

C-. You’ll never be OBL.

You were generous with the C-.....It deserved a D.

You feeling benevolent today, R Mac? 🙂

I had a good nights sleep.

"Some Republicans offered their own central planning proposals in the name of fighting China; others endorsed plans for a federal paid leave law and a universal basic income for kids."

I have never heard of this UBI for Kids proposal, so I looked it up. The only mention I found from during the Trump administration was a tax credit that Mitt Romney co-proposed with a democrat (Michael Bennet) in 2019:

https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2019/12/16/21024222/mitt-romney-michael-bennet-basic-income-kids-child-allowance

In other words, a proposal by two Democrats, one of whom pretends to be a Republican because he's not flaky enough for the Massachusetts Democrat Party.

The BIG QUESTION: WHEN?

"The reality is that one day, all that debt, cronyism, and lack of accountability will explode in our faces. "

Any ideas? [I'm thinking about buying another house for my kids to move into when it all comes tumbling down. Fortunately we have a lot of deer and turkey around us, and some space for a truck garden.]

Ligand for Target Protein

https://protac.bocsci.com/products/ligand-for-target-protein-3050.html

Protac® technology uses the ubiquitin-protease system to target and induce protein degradation in cells.

Many economist say the longer the economic collapse off is put off, the deeper and longer it will be when it comes. Maybe Biden is doing the US a favor, well two favors. First the collapse will be very bad, but sooner is still better than later. Second if the collapse comes during his or Harris's administration, another Democrat may not gain the White House for decades. Now that would be a real favor!

here everything u wanna know about