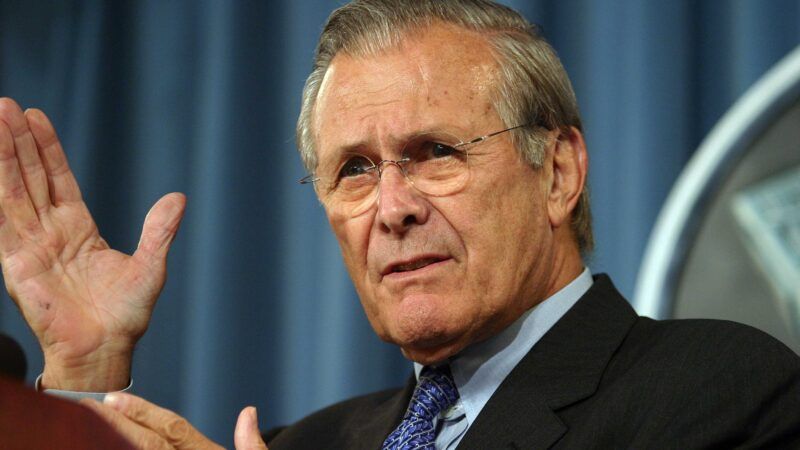

Donald Rumsfeld, Architect of Disastrous 21st Century Foreign Policy, Dies at 88

Upon his passing, it's worth remembering how badly things can go when a man has such great power, even a man with elements of conventional decency.

Donald Rumsfeld is dead at age 88 of multiple myeloma. He held many positions of power and respect in American institutions public and private over the past six decades, including naval aviator in the 1950s, Illinois representative in Congress in the 1960s, ambassador to NATO and chief of the wage-and-price-control-imposing Cost of Living Council under President Richard Nixon, and both chief of staff and secretary of defense to President Gerald Ford in the 1970s. In the private sector, he worked in senior management in companies including pharmaceutical firm G.D. Searle (1977–85) and electronics firm General Instrument (1990–93).

But Rumsfeld's most intense impact on his country and world history, and what he will doubtless be remembered for when all the other details have faded, was his role as secretary of defense under President George W. Bush when the U.S. launched its wars against Afghanistan beginning in earnest in October 2001 and against Iraq starting in March 2003 that overthrew its dictator Saddam Hussein; that war alone left over 4,000 U.S. troops dead and over 31,000 wounded in action.

The War in Afghanistan, 20 years on, is perhaps finally sputtering to a close with little gained and much lost. The Iraq invasion also happened in the aftermath of the 9/11 attack on the U.S., but Iraq had nothing to do with that. Intervention was justified with rumors of Iraq possessing weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) that were said to represent some threat to the U.S., but Rumsfeld was well aware we didn't really know whether they existed or not, and it seems after all they did not.

Rumsfeld already had placed his reputational weight before 9/11 behind the idea that the U.S. must do something to keep various imagined international foes from getting or having the sort of weapons we had, with the 1998 Rumsfeld Report. Rumsfeld was at least honest enough eventually to be doubtful about whether imposing the precious gift of democracy was a reasonable or worthwhile goal for invading. The invading was to be its own reward when neither WMDs nor democracy was a legitimate reason or excuse, in showing the world's bad guys they can expect the U.S. to go through any amount of trouble to topple them.

Attempts to topple bad guys in the Rumsfeldian spirit have continued to generate chaos and death in the Middle East ever since. Militias from Iraq, the nation Rumsfeld felt it necessary to ruin at nearly any cost, are inspiring the Biden administration to blow things up and kill people in the Middle East even to the week of Rumsfeld's passing.

Rumsfeld was intelligent enough to realize about a year in that the U.S. military occupation would take a long time, yet he believed that domestic critiques of his war policies were dangerous to the "ability of free societies to persevere."

After the GOP's bruising in the 2006 midterms, Bush finally let Rumsfeld go (though Rumsfeld insisted he tried to resign over the embarrassment of publicity surrounding abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib.) While Rumsfeld always purported to be proud of his role in Congress as a co-sponsor and advocate of the original Freedom of Information Act in 1966, he tried along with his old associate then-Vice President Dick Cheney to keep some of the darker facts about U.S. shameful behavior at Abu Ghraib hidden.

Long after departing office, Rumsfeld remained unrepentant and belligerent about the U.S.'s past and future roles on the world stage, and in a Republican context that then had to pay lip service to spending, he insisted that spending on war and preparation for conflict didn't count.

Rumsfeld was a major figure in the expansion of American wealth and reputation toward war and instruments of war, from his 1970s days in the Ford administration as a voice for new nuclear weapons systems and against arms reduction talks through Iraq and beyond. He never had serious second thoughts in public, and despite the cost in lives and civilization to Iraq over the past decades, he always believed it was the right thing to do, despite likely costs of nearly $6 trillion before the lifespan of those we sent to fight it are over, and 134,000 dead Iraqi civilians.

Like most human beings, Rumsfeld had human qualities that made some admire, appreciate, or love him, including famously helping the wounded into ambulances at the Pentagon on 9/11. In the end, it's not his fault that a position like "secretary of defense of the United States" and its concomitant power to command lives, technology, and wealth toward personal and civilizational destruction and misery exist, and better or worse men in certain terms may have done better or worse things with that office's awful power. But it is worth remembering as he passes just how badly things can go when a man has that power, even a man with elements of conventional decency.

Bonus: Check out Reason's Nick Gillespie's illuminating interview with Errol Morris, who made a revealing documentary about Rumsfeld:

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

"and against Iraq starting in March 2003 that overthrew its dictator Saddam Hussein; that war alone left over 4,000 U.S. troops dead and over 31,000 wounded in action."

The Iraq War was arguably a mistake.

However, plenty of decent, patriotic Americans supported it at the time. For example the leading neocon intellectuals (who are now basically establishment Democrats) like Bill Kristol, David Frum, Max Boot, and Jennifer Rubin. Heck, Joe Biden and Hillary Clinton were in the Senate at the time and IIRC both voted to give Bush the power to invade.

The point is that the early 2000s neocon GOP was far better than the modern alt-right white nationalist version. Orange Hitler's draconian war on immigration was far more violent and depraved than anything the US did to Iraq.

#LibertariansForABetterGOP

#PutTheNeoconsBackInCharge

You weren't in Iraq. The US, under Bush, Obama, Trump, and Biden, have slaughtered 100,000 people in Iraq. Do you have any pictures/proof of 100,000 dead immigrants?

Woosh!

Making money online more than 15$ just by doing simple work from home. I have received $18376 last month. Its an easy and simple job to do and its earnings are much better than regular office job and even a little child can do this and earns money. Everybody must try this job by just use the info

on this page.....VISIT HERE

This is getting way too boring and formulaic. Time for a new shtick.

I looking forward to his book.

Obviously, you have no idea what went on in Iraq or Afghanistan.

Nor the reasons why.

Maybe you should stop watching CNN for a change.

Arguably a mistake? It WAS a mistake. Or rather, a PURPOSEFUL MISTAKE.

Good riddance! One more non-Republican neocon gone.

Good thing neocon Boomers are dying by the thousands each day. That generation is one of the most commie generation, overall, America has ever seen. The damage Commie Boomers did might not be recoverable for America.

Far be it from me to defend the Boomers. But when they're go, think about what's replacing them.

https://thezman.com/wordpress/?p=24276

Fucking bigot

Cry more.

Yes, you are.

Rumsfeld wasn't a Boomer he was born in 33, more than 10 years before the baby boom era started.

Biden also is pre-boomer, but Trump barely qualifies.

Clinton, W. Bush, and Obama were all Boomers, and all easily replaced, Trump could have been easily replaced too, but we blew it.

I didnt say Rumsfeld was a boomer. I mentioned that he was a piece of shit AND boomers that supported his type of neocon bullshit are commies and their passing cant come too soon.

But hey, rumsfelds generation are bad too, they refused to cut social security and are leaving america with $25 trillion in debt, its not all their fault but those generations ran schools for decades along with boomers.

Gen xers arent off the hook either, but gen xers help dismantle pensions and unions moving toward 401ks and other private retirement saving plans.

Rumsfeld didn't make the decision to invade Afghanistan, Congress did 98-0 and 420-1. The Democratic majority leader Tom Daschle introduced the bipartisanly crafted AUMF.

So you may be able to blame Iraq on Rumsfeld, but you can hardly blame invading Afghanistan on him

Read up on the case for war involving rumsfeld.

Rumsfeld's obituaries falsely refer to him as a "conservative". But Rummy was always a war mongering "neocon" (like many so-called moderate Democrats) who believed the US should police the world.

Rummy was an Eisenhower Administration appointee before he ran for Congress. He was a conservative, just not a Goldwater/"New Right" con. Taftites would have put him down as an "internationalist." Your ur-neo-cons were ex-lefties who made common cause with the New Right, Chamber of Commerce Republicans and eventually the "social conservatives" of the evangelical Christian type: Irving Kristol, James Burnham of National Review. Commentary's Norman Podhoretz.

The problem with such nomenclature is that while traditional leftism has its roots in Marxist ideology, what a "conservative" is has changed over the decades. Late 19th century populists and 1930s-era New Dealers might get labeled "conservative" today because they would be on the "wrong" side of the 1960s counter-culture/establishment division.

BTW, if your Dad was a famous neo-con, and you follow in his footsteps, you are just a conservative. (Bill Kristol, John Podhoretz.)

People often make the mistake of thinking that conservatism is some defined set of beliefs, rather than an orientation towards the world and history.

He ran Great Society programs in the Nixon administration.

Republican, yes. Conservative? LOL.

Read up on Eisenhower. He was a “conservative democrat” and really didnt want to get into politics. Most americans back then were scared to admit they were not commie democrats like FDR. Revised history has FDR saving america during the great depression.

You couldnt get elected in much of america if you were a republican in those days so many politicians were “conservative democrats”. Truman was such a shitbag, that running as a republican was possible and Eisenhower ran as a republican because the democrat candidate was a party hack.

Necons are literally the hawk democrats that joined the GOP to make sure the military industrial complex was represented by both major parties. No true conservative wants to have bloated budgets for proxy wars and oversee bloated government departments.

True.

He held many positions of power and respect in American institutions public and private over the past six decades, including naval aviator in the 1950s, Illinois representative in Congress in the 1960s, ambassador to NATO and chief of the wage-and-price-control-imposing Cost of Living Council under President Richard Nixon, and both chief of staff and secretary of defense to President Gerald Ford in the 1970s. In the private sector, he worked in senior management in companies including pharmaceutical firm G.D. Searle (1977–85) and electronics firm General Instrument (1990–93).

And Robert McNamara was president of Ford. But we all know what he'll be remembered for.

Listen to this Viet Nam veteran's speech: McNamara's Folley/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=8&v=_J2VwFDV4-g

I hope Satan set him up with Sadam as his roommate. This mans hands are soaked with the blood of countless Americans, and even more foreigners. Our children's children will be paying for his pointless wars. Good riddance...

My thoughts. IT's when scumbags like him die that I hope hell exists.

Like most human beings, Rumsfeld had human qualities that made some admire, appreciate, or love him, including famously helping the wounded into ambulances at the Pentagon on 9/11.

It's also possible he could have been a completely different SecDef. AFAIK, coming into office his goal was more like Cap Weinberger or Les Aspin - to internally reform the Pentagon. A sorely-overdue prerequisite to changing foreign policy - and guaranteed to make internal enemies there.

Then 9/11 happened and as always black swan type events really change everything in the aftermath. They are the one type of event where its important to learn from history. Rumsfeld's death reminds us that - the clock is ticking to really learn those lessons. And we're not.

Tell us please, what's the lesson?

Do you have a book out?

What incredibly weak tea this obit is. The Iraq invasion was not some sadly inevitable consequence of the military industrial complex. Rumsfeld was not some faceless bureaucrat carrying out its imperatives. He was a deeply evil guy who, well before his second go round atop the Pentagon trained up Cheney and served Nixon. He was a primary architect of the worst foreign policy blunder in American history and he should be remembered for it. And just because bovine Dems voted to invade Iraq doesn't mean that war would have happened had the Florida election mess gone the other way.

He was a primary architect of the worst foreign policy blunder in American history

I consider him neck-and-neck with McNamara.

just because bovine Dems voted to invade Iraq doesn’t mean that war would have happened had the Florida election mess gone the other way.

Why? Because you say so? Who are you asserting were the foreign policy and defense names in Gore's rolodex? Answer is - you can't possibly know and neither did any voters because that is NEVER an issue in any election EVER. Period. Most voters do not remotely give a shit about selecting a competent president. Only a comfortable drinking buddy or BFF. They never will either - and probably couldn't - and there is no process that might allow some small subset of voters (beyond the beltway/swamp) to treat the election with the serious of say selecting a CEO. Nor will the media do that as anything other than a third-party gotcha - see Aleppo.

Hasn't always been this way.

Before the Civil War, only three Presidents did NOT have significant foreign policy or military experience on their resume - Tyler, Polk, and Fillmore. Even if voters didn't take that experience seriously, the parties who nominated those folks did.

Since WW1 only two Prez HAVE that experience - Eisenhower and PapaBush. Though maybe add two with lower-level experience (Hoover and FDR).

This is one of the costs of elections based on charisma/rhetoric/mass media. The people elected become either figureheads or gullible.

Nixon and Kennedy both served in the Navy. I think Nixon spent his time playing poker on an island in the pacific and was so skillful a player that he was able to finance his early political career from his winnings when the war was over.

For military, I'm talking about commanding as a general or prev experience as SecDef. For foreign policy, being a major ambassador or prev experience as SecState.

The notion of having already had the experience of the people you will now manage as Prez - so you can manage them rather than be managed by them. That was a notion then. Not now.

What I blame him for is his refusal to listen to those who told him his plan to govern post-invasion Iraq wouldn't work. Or should I say, his expectation that post-invasion Iraq would just keep chugging along as before.

even a man with elements of conventional decency.

Because to get back to conventional decency, we're willing to throw everything into the incinerator.

I will shed no tears for Rumsfeld. I was with the 278th ACR in Kuwait when one of our soldiers asked him about why our vehicles were not uparmored and he gave his "you go to war with the Army you've got" answer.

It was completely dishonest. For one thing we were three years into the war at that point and we should have been better prepared (South Africans, for instance, had had mine resistant vehicles since the 80s). For another we got brand new LMTVs for our deployment, but apparently no one thought to either add the up-armor kits or ship them with the trucks so we could add them in theater. So instead our mechanics scrounged what they could and that is where "hillbilly armor" came from.

If Bush would have fired him before the 2006 elections the Republicans might have retained the House. Instead Rumsfeld resigned a few days later, Gates was a much better SECDEF.

Thanks for answering the call, 68W58. Have a great holiday weekend.

Is that the same Gates that was bipartisan enough that Obama kept him on as his own SecDef, and then later said that Biden had been wrong on every single foreign policy decision he had ever been involved with?

The man is a good judge of character.

I will shed no tears for Rumsfeld. I was with the 278th ACR in Kuwait when one of our soldiers asked him about why our vehicles were not uparmored and he gave his “you go to war with the Army you’ve got” answer.

I have never been able to stand that stupid cliche: "You go to war with the Army you've got!" What bullshit! The U.S. damn sure never did that in World War II.

Very shortly after Pearl Harbor, all but three of the attacked ships were repaired and made seaworthy and battle-worthy!

Although a draft existed, it really wasn't necessary because everyone, even teenaged boys fudging about their age, were lining up at recruiting offices to go and fight!

Factories were retooled for wartime production of the latest and greatest models of tanks, Jeeps, Armored Personnel Carriers, and fighter planes and women became "Rosie The Riveter" working side-by-side with men!

Our greatest scientists participated in The Manhattan Project and harnessed the power of the atom and as Rush put it: "Shot down The Rising Sun!"

In other words, in World War II--our last Constitutionally-declared war--we took the Military we had--Army (including the Air Force predecessor, The Army Air Cotps,) Navy, Marines, and Coast Guard--and we made that Military better by orders of magnitude! Then we moved on to see that Fascism, National Socialism, and Hirahitoism did not take up one square inch of dirt on the face of this Earth!

Donald Rumsfeld wouldn't be worthy of doing KP duty for the U.S. Military of World War II!

By the way, 68A58, despite the U.S. Government's awful foreign policies, I do thank you and your fellow Armed Servce Members for your service! Every day is Memorial Day and Veterans Day whenever I meet one of you!

The US army absolutely went to war in WWiI with the army it had. The US army got their ass kicked multiple times because our military strategy lacked in multiple areas except logistics.

The Grant/Sherman/Stuart were pieces of crap compared to tanks of USSR/Germany but swarmed enemies.

All early WWII USA fighters were crap compared to Axis fighters.

American generals had huge differences in abilities. German generals in 1942 were almost without exception far superior tacticians/strategists/leaders than American generals.

...

Barry Obama was such a good president that he decided, over eight years, to keep going in Afghanistan so he could let his successors get the blame when the shit hits the fan. Fortunately that sucker is his footrest named Joe Biden.

Cause of death: unknown known

finally off to the unknown unknown

Shamelessly stolen from elsewhere:

Finally something worth celebrating this year! Rumsfeld's warming his toes in hell now.

No mention of the role he had to have had shutting down air defenses on 9-11?

Four rogue airliners

Twice wide open WTC, including a long delay

Wide open Pentagon (please!)

NORAD military readiness rules ignored that morning

No available air defenses Boston to NYC to PA to VA?

Seriously???

Also he did nothing to soothe hemorrhoids. Or aid paraphelgic Aleutian Indian lesbians.

Neither of which were his job. Defending the U.S. was. Nice Stawman you set up there.

Nothing wrong with Rumsfeld's foreign policy - it was right for the time. Judging it with woke hindsight is the mark of mal-educated micro-minds.

"Nothing wrong with Rumsfeld’s foreign policy "

It was lazy, deceitful and overly ambitious. The first invasion of Iraq under the first Bush had limited goals and an enormous international coalition behind it. Bush even had to sacrifice US support for Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge of Cambodia in order to get his international ducks in a row.

No, I hated his forign policy at the time and I still do today!

And by the bye, don't knock Armchair Quarterbacks. At least they learn from history.

No, it wasn't right for the time. It was a fucking terrible idea. There was no link between Saddam and the Sep. 11th attacks, and (aside from some mustard gas canisters) no actual WMD's that would hurt us or our allies. Trump was spot on with his assessment of the war

"“The worst single mistake ever made in the history of our country: going into the Middle East, by President Bush. Obama may have gotten (U.S. soldiers) out wrong, but going in is, to me, the biggest single mistake made in the history of our country.... we spent $7 trillion in the Middle East. Now if you wanna fix a window some place they say, 'oh gee, let’s not do it.' Seven trillion, and millions of lives — you know, ‘cause I like to count both sides. Millions of lives.”

LOL - he's a micro-mind? You're a dummy 🙁

There's an interesting take on unknown knowns by philosopher Slavoj Zizek, who is also an authoritarian Marxist, nicknamed the Elvis of Cultural Theory. 'Things we know but we don't even know that we know them. That is to say, ideology.'

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ql80Klk4pSU

You know who else was famously unrepentant about his invasions and occupations?

Bill Cosby?

You Bet Yer Flozzum-Flip!

The decisions to invade both Afghanistan and Iraq, were not just Rumsfeld's alone. There are other actors who greatly influenced that administration: one of them was AIPAC. How many others of their ilk that slithered their way into Washington in order to make America Israel's bitch?

The truth is , the decision to invade Iraq was made months before the 9/11 false flag. Months.

It had nothing to do with 9/11. It had and continues to have everything to do with Israel and its sayanim working inside Washington.

It has everything to do with Israel's quest to dominate the entire middle east, first by getting America to invade, bomb and turn every other nation there, into hell holes, thus creating chaos throughout the middle east. Therefore Israel would reign supreme and get away with anything they wish. Which they do so now.

Rummy was just one of the conduits.

America sacrificed thousands of its young people and untold numbers of lives destroyed in Iraq and Afghanistan. Iraq is no longer a viable nation. Afghanistan is a narco state. heroin is its main industry, run by the CIA and Pentagram.

The American people having been forced to once again shed its blood and exhaust its wealth on such foreign debacles for the sake of a tiny state that claims in its self righteous, delusional idea that somehow it is king of the world.

Rumsfeld was also instrumental in getting Aspertame into the food chain.

here everything u wanna know about

With everything going on in the world right now, I don't understand why this people won't just leave politics for a day and do the right thing.

read some news here