International Travel Is Partially Back, but It's Worse Than Before

Border restrictions and testing requirements make vacation a bit less relaxing and a lot more expensive.

"Police are stupid," Kostas the taxi driver explained to me and my two buddies last week, informing us that we would all have to remain in the back seat of his cab for the duration of our hourlong trip. We'd recently arrived in Athens from New York (me and my husband) and Leipzig (my brother) and were unaware that Greek police now hassle taxi drivers for allowing people in the front seat, due to COVID-related restrictions.

Though Kostas spoke the truth, restrictions like these were the least cumbersome part of the trip. In the 16 months since I'd last traveled out of the country, pandemic regulations have exacerbated the inconveniences and indignities that already accompanied travel—while also jacking the cost up.

Greece is one of the few European Union countries that currently allow vaccinated Americans or those with a negative COVID test result from the last 72 hours to skip quarantines completely. Still, the day before entry into the country, you must fill out a Passenger Locator Form (PLF) detailing information about your country of residence and where you've been recently, which then provides you with a unique QR code on the day of travel, which you present to the authorities. To the Greek government's credit, it destroys this personal information 23 days after using it; it uses the screening data to decide which travelers ought to be directed to additional COVID screening upon landing. All of this, like many other COVID measures, relies on travelers answering questions truthfully; as I filled out my form, I wondered how many people lie for convenience, to evade onerous additional requirements.

At Newark, United struggled to handle the task of checking for every passenger's PLFs, vaccination cards, or recent test results, delaying boarding and takeoff significantly as passengers attempted to make sense of the chaos at the gate. No person was clearly directing people to queue up to present their documents, so some spontaneous order emerged as people slowly caught on to the procedure.

Meanwhile in the E.U., my brother failed to grasp that the PLF needed to be filled out prior to midnight, realized the morning of his flight from Leipzig to Athens that this would present a problem—his own fault, but a fault that required him booking a new flight that had a five-hour layover in Belgrade, Serbia, just so he would land in Athens technically past midnight at 3 a.m., satisfying the government's requirements. His risk of contracting or spreading COVID could arguably be increased by the five hours he spent hanging out at a random bar in Serbia, but bureaucratic logic doesn't often grapple with the warped incentives it creates.

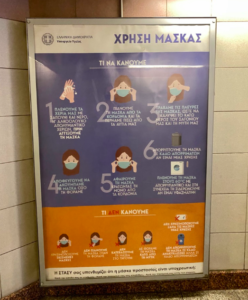

Once we got into Greece, the situation on the ground was blessedly normal. No indoor dining, but plentiful outdoor seating. Masking was still required outdoors at tourist sites like the Acropolis and was expected at religious sites. Before boarding some ferries, we had to fill out additional health screening forms, though they didn't ask for additional proof of vaccination (and they would have been easy to lie on). Police are apparently somewhat strict about enforcing mask wearing in cars with multiple passengers in them, so after dining and smoking and drinking with a new friend and his wife, in close proximity for many hours, we donned our masks in his car as he drove us back to the train station.

Despite being fully vaccinated, my husband and I belatedly realized we needed to get PCR test results in Greece to present before getting boarding passes to be allowed back into the U.S. So, we booked it to the Metropolitan Hospital of Athens toward the end of our trip, forked over 120 euros (plus cab fare both ways), and were presided over by a woman in a face shield. Gesturing at the face shield, I asked: "Does it work?" You'd think nurses of all people would know the answer—that aerosolized viruses are not really stopped by plexiglass or plastic shields with openings around them, just as door handles and subway cars obviously don't need to be scrubbed down—but I quickly dropped the questioning, deciding this was not the time or the place to wage my fruitless war against bad COVID science.

Governments have long monitored who arrives and departs their countries, where they're from, how long they stay, what they bring and take with them. I wasn't surprised that they have continued to do so during a global pandemic, especially as new variants spread, but I was struck by how poorly targeted these measures were. When getting boarding passes to return to the U.S., I was questioned about whether I've been in India or the U.K. within the last few weeks—ostensibly a question about travelers who have been in places where high numbers of variants have been detected, but not necessarily one that makes sense, given what we know about how quickly they're spreading or how easy it would have been to mislead authorities. A rapid test at the airport would have probably been more effective if they were actually attempting to do a thorough screening.

Negotiating this patchwork of restrictions and intrusions was a small price to pay for me to reenter the E.U., where my brother has lived for the last six years. For families split up by borders, pandemic restrictions have presented major financial and logistical burdens, especially for people—like my brother—who do not work desk jobs and have to sacrifice shifts at work to quarantine upon return to their country of residence.

The costs to travel have gotten a good deal higher, but they're costs I'm personally happy to pay. I have no confidence, though, that governments will roll back these restrictions once the threat of the virus is appropriately suppressed; parts of all this hygiene theater and health monitoring may outlast their welcome. From my vantage point, they already have.

Show Comments (39)