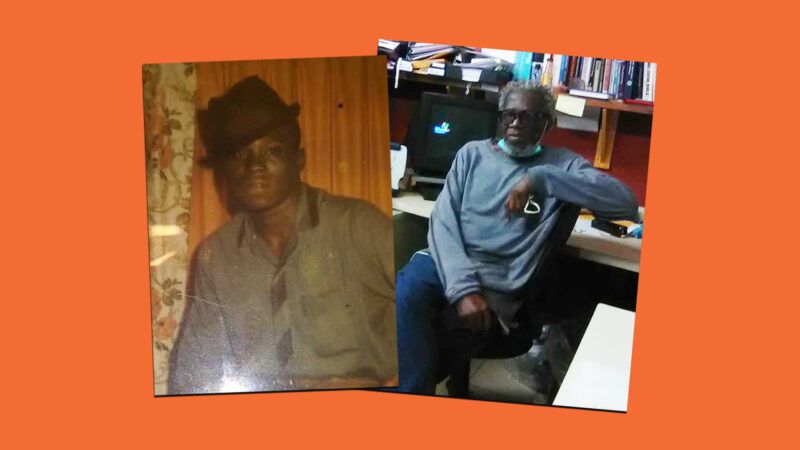

Louisiana Can't Prove This 74-Year-Old Inmate Took Drugs. They Revoked His Parole Anyway.

After spending 47 years behind bars, Bobby Sneed may die in prison for no good reason.

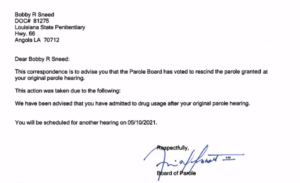

Bobby Sneed, a 74-year-old inmate at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, was granted parole and scheduled to be released in March after serving 47 years behind bars. But he was never set free. He is now likely to die in prison, after the Louisiana Board of Parole revoked their decision in response to a contraband charge that a disciplinary committee formally admitted they cannot prove.

On March 25, four days before his scheduled release, Sneed was hospitalized after collapsing. According to disciplinary records, he allegedly tested positive for amphetamines and methamphetamines while at the R.E. Barrow Treatment Center, after which point he was told he would not be going home. He was instead moved to administrative segregation, also known as solitary confinement, where he has been for over a month now.

Yet at the disciplinary hearing held on Wednesday to adjudicate the matter, the charge was dropped—because the committee was forced to concede they didn't know who the drug-infused urine actually belonged to.

"They didn't have a complete chain of custody, so there ended up being no proof that the urine samples that tested positive for drugs actually was [sic] Bobby's," Thomas Frampton, Sneed's attorney, told me that day.

The committee immediately furnished a new charge, alleging that Sneed was in the wrong dorm when he collapsed and was therefore guilty of trespassing. That charge was dropped Thursday.

"The Louisiana State Penitentiary Disciplinary Board dismissed both charges against Bobby Sneed this week," said Ken Pastorick, communications director for the Louisiana Department of Public Safety & Corrections, in an email yesterday. "The parole of Sneed is a decision for the Parole Board, an autonomous board independent of the Department of Public Safety and Corrections."

Indeed, the board proceeded as if the charges from the Department of Corrections were still looming over Sneed's head. "We are able to rescind parole decisions when an offender has violated the terms of the decision granted by the board or has engaged in misconduct prior to the offender's misconduct," says Francis Abbott, the executive director of the Louisiana Board of Pardons & Committee on Parole. "What was the misconduct?" I ask. "We've got documents that were submitted to the board that are not open to the public," he says.

Frampton is among those not privy to the evidence of misconduct against his client, though Abbott did relay to him that it was a singular member of the board who upended the original decision.

"It's just pointless cruelty at this point," says Frampton. "The Parole Board's latest move just shows contempt for the law, public safety, common sense, and the taxpayer money."

Those taxpayers will now be spending tens of thousands of dollars to keep Sneed locked up, probably for the rest of his life.

Sneed was arrested in 1974 after standing guard two blocks down the street while some of his accomplices robbed a home, during which time they killed one of the residents. He did not participate in the killing—something no one disputes—but he was convicted of principal to commit second-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison. Out of all of the men wrapped up in that crime, he is the only one still in prison.

"Two of Mr. Sneed's co-defendants agreed to testify and served no time," his parole file reads. "One co-defendant struck a deal with the state at the time of Mr. Sneed's second trial and received a reduced sentence. One co-defendant died in prison and [another one] was released on parole."

It appears that Sneed might also die in prison. Not because he's still a danger to society: The board acknowledged he was no such thing in the glowing 17-minute hearing that resulted in their unanimous March decision. It will be because of a drug charge—something that is both victimless and unsubstantiated. That's not justice. That's a travesty.

Show Comments (37)