The Real Inflation Risk Is Political

The short-term inflation outlook isn't as grim as it looks, but the long-term situation could be awful

As America exits the COVID-19 pandemic, demand for goods and services is surging—and triggering worries about inflation.

The consumer price index for March showed a 2.6 percent increase over the same month last year. That's the largest year-to-year increase in prices since the summer of 2018, and significantly more than the 1.4 percent year-to-year increase that was being reported just two months ago. Meanwhile, the White House Council of Economic Advisors warned this week that "measured inflation" is likely to increase over the next few months. And the price of gasoline—perhaps the most obvious signal of rising prices, at least for those of us who don't hold advanced degrees in economics—has been steadily marching upwards since the start of the year.

Should we be worrying about a return to the rampant inflation of the 1970s?

For now, the fear is probably premature, says David Beckworth, a former Treasury Department economist now affiliated with the Mercatus Center, a free market think tank at George Mason University.

"The economic indicators aren't flashing any red alerts right now," Beckworth tells Reason, "but the political economy is more worrying."

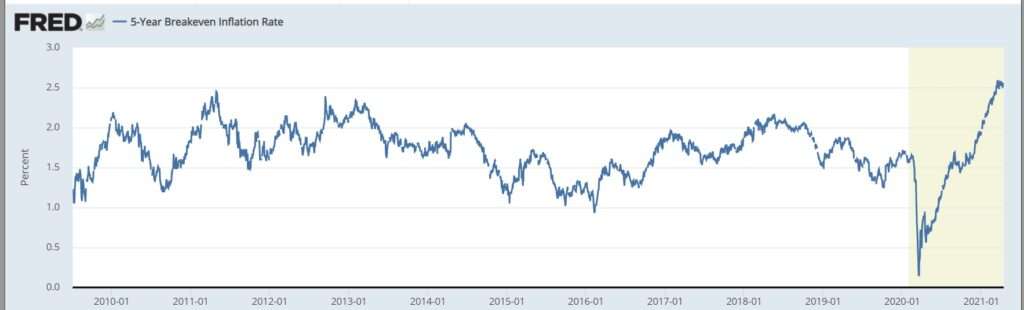

One of the best indicators of future inflation is the "breakeven inflation rate," which measures the difference in yield between bonds that are pegged to inflation and those that are not over the same period of time. The five-year breakeven inflation rate—in other words, how inflation investors are anticipating over the next five years—has been increasing, but it currently sits just slightly higher than its post–Great Recession average.

So if runaway inflation is on the horizon, investors aren't anticipating it. Even if inflation spikes in the short term, they don't appear to expect historical highs over the course of several years.

The rising CPI might not be a major cause of concern, either. It's a backward-looking economic indicator—comparing prices today to what they were a year ago—so it's capturing some of the economic weirdness that the pandemic created last spring, when prices fell as demand sank and much of the country entered lockdown.

The biggest contributor to the rising CPI in March was the surge in gasoline prices, which were up 22 percent from last year. But that says as much about last spring's drop in gas prices—due to a sudden glut of supply as many people stopped traveling and commuting—as it does about where things sit now.

For a similar example, think about the markets for airline tickets and vacation rental homes. Many Americans had travel plans cancelled last summer, and that backlogged demand will likely be unleashed in the coming months as an increasingly vaccinated population reunites with far-flung families and friends. A sudden increase in demand in markets where supply can't rapidly grow to match it is a recipe for higher prices. But that's a short-term situation that will work itself out, not a long-term increase that could wreck standards of living and retirement plans.

"We think the likeliest outlook over the next several months is for inflation to rise modestly due to the three temporary factors we discuss above, and to fade back to a lower pace thereafter as actual inflation begins to run more in line with longer-run expectations," the White House economists conclude.

That's the economic side of the inflation situation. It should provide some comfort. The political side is a different story.

"What ultimately will cause inflation to take off is a sustained increase in the growth of government spending," says Beckworth. "If we do these big spending packages and there's not an immediate increase in inflation, it enables us to be more complacent about future government spending programs."

The federal government pumped $1.9 trillion into the economy in March. While that was a one-time infusion of newly printed money, the Biden administration is also proposing permanent increases to the baseline federal budget and pushing for a $2.3 trillion infrastructure package that is likely to be at least partly financed with deficit spending.

Even without those spending increases, deficits are set to grow in coming years, largely because of entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare that run on autopilot.

And all that is happening at a time when both major parties have abandoned any pretense of concern about overspending. The alarm bell of a rising CPI might be the only real check on the political incentives that keep the cost of government growing—and pave the way for more substantial inflation down the road. And the alarm bell isn't ringing. Yet.

Show Comments (51)