Why Isn't California Safer From Wildfires?

An environmental law keeps public agencies from reducing wildfire fuel.

It's been four years since the North Bay Fires in California devastated Sonoma, Napa, and Mendocino, and three years since Paradise was nearly wiped off the map. Until last year, 2017 was the largest wildfire season on record, with more than 1.5 million acres burned in the wake of six years of drought.

This past year blew that record away—2020 was the largest wildfire season in California's recorded history, with 4.2 million acres burned by 10,000 wildfires.

The severity of the 2020 fire season and the number of forest fires that move from the floor up to the canopy are clear evidence that we have not done enough. Our forests are not healthy, and lives and property continue to be at risk.

We know all this. Wildfire risk is a top concern of fire agencies, legislators, and residents alike. So why aren't we safer?

The biggest hurdle is the well-intentioned California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), which introduces layers of uncertainty and complication, holding up much of the fire prevention work identified after 2017.

Fires are a function of weather, topography, and fuel. We have control over only one of these: how much fuel there is to burn. Over 100 years of continuous fire suppression have disrupted the natural fire cycles of California's forests. Tons of underbrush, dead trees, and drought-starved vegetation that would naturally be cleared by wildfire have continued to accumulate. About 11.2 million people in California live in or near forests in what's called the wildland-urban interface (WUI), more than in any other state.

After the devastation of the 2017 and 2018 fire seasons, fire agencies in high-risk areas got to work identifying fuels reduction projects that would prevent or lessen the effects of the next fires. Vegetation management is a balance—no one wants zero risk of fire at the cost of a bare landscape. Perhaps now the community would be willing to tolerate more of these projects than before in order to make a difference.

But before a public agency can start a fuels reduction project, whether it is simply limbing up trees or creating a shaded fuel break in open space, it must comply with CEQA.

Enacted in 1970, CEQA requires analysis and public disclosure of environmental impacts of "projects." Any alteration to the landscape that is discretionary—even mandating that property owners pick up dead tree limbs—could be considered a project under CEQA.

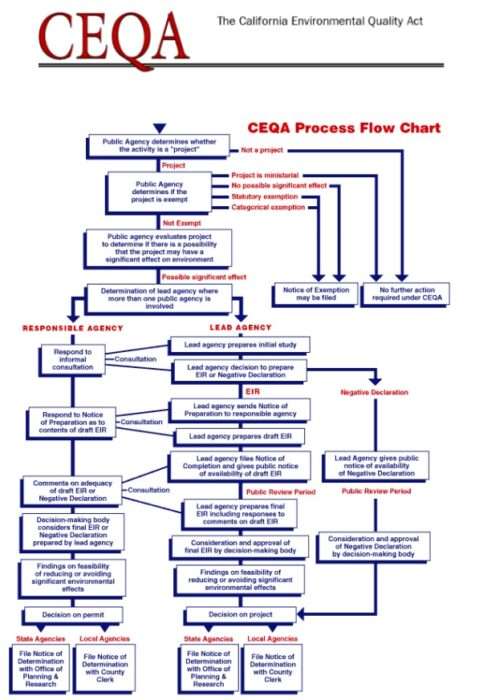

For example, a fire agency determines that a ridgetop fuel break would prevent a fire from spreading to the homes nearby. Implementing this is not a simple process. First, the agency must define the project and determine whether it can be considered exempt under one of several categories or statutes. There may also be exceptions to the exemptions. If the project is not exempt, the agency performs an Initial Study to determine potential impacts, whether those impacts are significant, and whether they can be mitigated. If so, it can prepare a Negative Declaration or a Mitigated Negative Declaration. If it can't do that, it must produce a full Environmental Impact Report (EIR). Following through to a complete EIR is a time-consuming and costly process, ranging from $200,000 to millions of dollars over multiple years. It is impossible to budget or plan for this process without some level of scoping and detailed analysis by a CEQA expert.

A vegetation management project tends to cover a larger project area than a development project, so the cost to analyze the impacts will tend toward the higher side of the range. There is generally more work to be done than there are funds, so the CEQA compliance costs will reduce the reach of funds meant for prevention work, evacuation planning, and community outreach.

Even completing a thorough EIR, as the Board of Forestry and Fire Protection did with its California Vegetation Treatment Program (CalVTP), doesn't protect agencies from lawsuits.

Fire prevention officers are not trained in CEQA analysis. Some agencies, like those in Marin County, are considering hiring full-time staff with expertise in navigating CEQA, but many agencies don't have the funds for that. Wildfire fuels reduction has gotten the attention of local activists, who fear fire agencies are out to denude the landscape without heed to habitats, nesting seasons, or the natural beauty of the landscape. This is what CEQA was meant to address, but the concerns of impacts from fuels reduction work must be balanced against the catastrophic effect of a megafire on the landscape.

The state government is well aware that CEQA needs reform. Former Gov. Jerry Brown called reforming CEQA "the Lord's work," but eventually threw up his hands. CEQA is a favorite tool for labor and anti-development groups looking to block a development project, so legislators are leery of wading into serious reform. A stadium project is more likely to be statutorily exempt from CEQA than a wildfire fuels reduction project. Working around this stumbling block, Gov. Gavin Newsom fast-tracked 35 wildfire prevention projects in 2019, and each year there is a scramble to get projects on this coveted list.

Newsom just approved $80 million in emergency funds to bring on additional firefighters to bolster fuels management and wildfire response. Agencies can't take full advantage of these efforts and funds if they can't get projects through the CEQA process.

Newsom and the legislature need to take on reforms to CEQA—not for development, but for wildfire prevention. Allowing simple fuels reduction projects to be exempt from CEQA would be a great first step. Crucial reforms may not be as scary as some politicians think. Labor groups are not likely to oppose exemptions that have nothing to do with development.

Fire season has already begun this year. Today, nearly all of California is in moderate to severe drought conditions. The political will is there. Now all we need is reform to allow fire agencies to do the work we all pray gets done before the next megafire.

Show Comments (28)