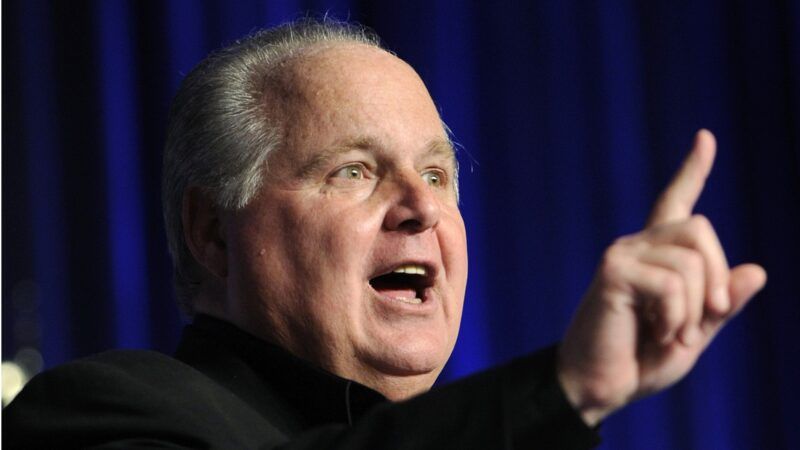

The Fairness Doctrine Was the Most Deserving Target of Rush Limbaugh's Rage

He was no libertarian, but he absorbed an important lesson about regulating speech.

Rush Limbaugh's half-century career in radio began as a 16-year-old at a small station in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, in 1967. (If you just muttered to yourself, "Where?" then you've already got a good sense of how unlikely Rush's rise to prominence was.) Notably, one of Limbaugh's first jobs in radio was in community ascertainment, which meant canvassing local businesses, churches, and interest groups to ask about the kinds of content they wanted to hear on the airwaves. The programs produced because of these expeditions were then parked on the least desirable time slots of the week, like Sunday morning.

Station owners were not, after all, truly owners; they were merely borrowers, temporarily using a slice of the electromagnetic spectrum via a license granted to them by the federal government. That license came with strings attached.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) required community canvassing as part of its requirement that stations operate in the "public interest, convenience, or necessity." License holders couldn't just air whatever content they wanted (or what they thought their listeners wanted). No, they had a vague responsibility to air programming that their listeners needed, and to do so whether or not listeners actually, well, listened.

In the 1960s, the FCC began enforcing another outgrowth of the public interest mandate which was known as the Fairness Doctrine. It stipulated that station owners had an obligation to provide coverage of "controversial issues of public importance"—like current events, policy debates, and so on—and do so without exclusively representing a single point of view. If, say, a station aired a program that criticized the U.S. conduct of the war in Vietnam, then it had an obligation to air someone supporting the war effort. Long before Fox News adopted the slogan, the FCC sought to make the airwaves a "fair and balanced" medium.

The FCC's commitment to the concept proved equally notional. In the early 1960s, the Kennedy administration quickly realized that the Fairness Doctrine could be useful as a tool for suppressing political dissent. If the fairness mandate was applied selectively—only forcing stations with conservative programming to increase the amount of liberal programming they aired and not vice versa—the administration could simultaneously punish their right-wing critics and extract free pro-administration airtime.

I tell that story in detail in my book The Radio Right: How a Band of Broadcasters Took on the Federal Government and Built the Modern Conservative Movement, but suffice it to say here that the Fairness Doctrine enabled the most successful government censorship campaign of the last half century. It might, with greater accuracy, be titled the Unfairness Doctrine, given its use to suppress political dissent and protect the lies of incumbents from both major parties, including Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon.

By the early 1970s, the targeted conservative broadcasters had largely been silenced, but the memory of the Fairness Doctrine era left an impression on a young Rush Limbaugh. It remained one of his most common topics of conversation until the end of his life; he mentioned the Fairness Doctrine on more than 140 episodes of his show since 2007. As he said in 2010 during a previous wave of interest in reviving the mandate, "Just like the Fairness Doctrine, I know what these guys have in mind, I know what their game plan is….Use intimidation, license renewal, fines, all this kind of thing." These were the tactics used in the 1960s to suppress conservative broadcasters, something that Limbaugh never forgot.

Indeed, Limbaugh owed his rapid rise to the repeal of the Fairness Doctrine by the Reagan administration in 1987. Limbaugh had been hosting a political talk radio show for a few years prior, but it wasn't until 1988 that a radio network executive decided to test the post-Fairness Doctrine waters by syndicating The Rush Limbaugh Show on 56 stations nationwide (which expanded to more than 600 stations by the mid-1990s).

It is also worth noting that talk radio in the 1980s was a much more ideologically diverse industry than it is today, with many hosts from both the political left and right. Contrary to conservative talk radio hosts who explain their dominance by the existence of a silent majority of average Joe listeners, ironically it was the federal government that boosted right-wing dominance of talk radio.

As historian Brian Rosenwald argues, left-wing talk radio hosts had to compete for listeners with government-subsidized, center-left NPR affiliates, while right-wing hosts had a clearer competitive field. Station owners could guarantee a larger audience to advertisers simply by picking right-wing instead of left-wing talk radio programs. Talk radio's conservative bent is the unintended product of the government's halfhearted attempt to create a nationalized broadcasting system in the 1970s. (Though I wouldn't expect a "Rush was Made Possible By Listeners like You" slogan to appear on a complimentary NPR tote bag any time soon.)

Limbaugh's death comes at a time of increased interest in creating Fairness Doctrine-style regulations for the internet. The broadcast Fairness Doctrine—which was dependent on the legal fiction of spectrum scarcity—can't be directly applied to the unlicensed and unlimited World Wide Web. But where there is a political will, there is usually a regulatory way. In this case, those seeking to guarantee political neutrality could tinker with the Section 230 platform liability waiver to mandate something with a similar effect as the Fairness Doctrine.

The passing of Rush Limbaugh is a reminder that the chilling effect of the Fairness Doctrine era is passing out of living memory. But while Limbaugh's concerns about a resurrected mandate might have sounded paranoid in the 1990s and 2000s, they feel somewhat prescient in 2021.

Show Comments (133)