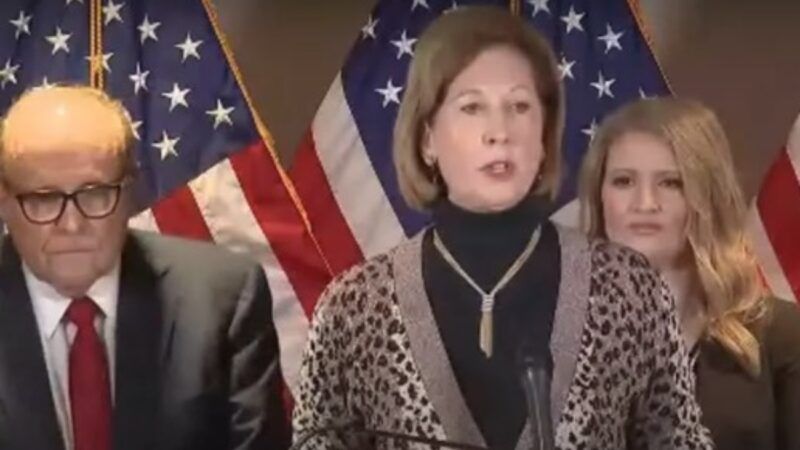

A Federal Judge in Michigan Says Sidney Powell's Election Fraud Claims Are 'Nothing but Speculation and Conjecture'

According to the ruling, the former Trump attorney also filed the wrong claims in the wrong court at the wrong time on behalf of the wrong plaintiffs.

A federal judge in Michigan today rejected former Trump attorney Sidney Powell's attempt to decertify that state's presidential election results, finding that her claims failed in almost every possible way. "This lawsuit seems to be less about achieving the relief Plaintiffs seek—as much of that relief is beyond the power of this Court—and more about the impact of their allegations on People's faith in the democratic process and their trust in our government," U.S. District Judge Linda V. Parker writes in her 36-page opinion. "Plaintiffs ask this Court to ignore the orderly statutory scheme established to challenge elections and to ignore the will of millions of voters. This, the Court cannot, and will not, do."

Powell alleged "a massive election fraud" aimed at "illegally and fraudulently manipulating the vote count to manufacture an election of Joe Biden as President of the United States." This scheme purportedly included "the unlawful counting, or manufacturing, of hundreds of thousands of illegal, ineligible, duplicate or purely fictitious ballots in the State of Michigan," representing "a multiple of Biden's purported lead in the State."

The Michigan lawsuit was part of what Powell had described as a "Kraken" of overwhelming evidence that, once released, would lay waste to any remaining skepticism about the president's claim that he actually won the election. Parker was not exactly awestruck at the sight of Powell's hideous creature, which upon close examination she found to be composed of "nothing but speculation and conjecture."

Powell claims that election machines in Michigan (and around the country) were rigged to give Biden a lead. But "the closest Plaintiffs get to alleging that election machines and software changed votes for President Trump to Vice President Biden in Wayne County," Parker says, "is an amalgamation of theories, conjecture, and speculation that such alterations were possible."

Powell maintains that Democrats resorted to paper ballot fraud after their original, machine-based scheme failed to work as anticipated. Yet "the closest Plaintiffs get to alleging that physical ballots were altered" to favor Biden, Parker says, "is the following statement in an election challenger's sworn affidavit: 'I believe some of these workers were changing votes that had been cast for Donald Trump and other Republican candidates.' But of course, '[a] belief is not evidence' and falls far short of what is required to obtain any relief, much less the extraordinary relief Plaintiffs request."

What about Powell's reiteration of the complaint that Detroit election workers treated Republican poll challengers rudely and inappropriately? "Plaintiffs do not at

all explain how the question of whether the treatment of election challengers

complied with state law bears on the validity of votes, or otherwise establishes an

equal protection claim," Parker writes.

In addition to highlighting the paucity of Powell's evidence, Parker concludes that her claims are barred by the 11th Amendment, which generally keeps federal courts from getting involved when citizens sue states. Deference to state courts would be appropriate in any event, she says, because when Powell filed her complaint "there already were multiple lawsuits pending in Michigan state courts raising the same or similar claims."

Parker also ruled that the six presidential elector nominees who were listed as plaintiffs did not have standing to sue for alleged violations of the constitutional provisions governing federal elections. Neither did they have standing as voters to pursue their equal protection claims, Parker says, because the injury they asserted (dilution of their votes) would not be addressed by the remedy they sought (tossing out millions of other people's votes).

Even if the plaintiffs had standing, Parker says, their lawsuit would be moot because Powell did not file it until November 25, after Michigan had certified its election results and submitted its slate of presidential electors. "Plaintiffs did not avail themselves of the remedies established by the Michigan legislature," Parker writes. "The deadline for them to do so has passed. Any avenue for this Court to provide meaningful relief has been foreclosed."

Powell's tardiness also figures in Parker's determination that the lawsuit is barred by the doctrine of laches, which applies when a defendant is prejudiced by a plaintiff's unreasonable delay in pursuing a claim. Parker's criticism of Powell on that score is withering:

Plaintiffs showed no diligence in asserting the claims at bar….If Plaintiffs had legitimate claims regarding whether the treatment of election challengers complied with state law, they could have brought their claims well in advance of or on Election Day—but they did not….If Plaintiffs had legitimate claims regarding the manner by which ballots were processed and tabulated on or after Election Day, they could have brought the instant action on Election Day or during the weeks of canvassing that followed—yet they did not….If Plaintiffs had legitimate concerns about the election machines and software, they could have filed this lawsuit well before the 2020 General Election—yet they sat back and did nothing….Plaintiffs could have lodged their constitutional challenges much sooner than they did, and certainly not three weeks after Election Day and one week after certification of almost three million votes [for Biden].

According to Parker's ruling, in short, Powell filed the wrong claims in the wrong court on behalf of the wrong plaintiffs at the wrong time. Even if she had not erred in all of those ways, her evidence of election fraud was too meager to provide the basis for the injunction she sought. Still, it's fair to say that Powell's Kraken is just as formidable as ever.

Show Comments (212)