Trump: If the President Doesn't Have Standing to Pursue Wild, Unsubstantiated Claims of Election Fraud, Who Does?

Fox News interviewer Maria Bartiromo uncritically accepts Trump's outlandish conspiracy theory.

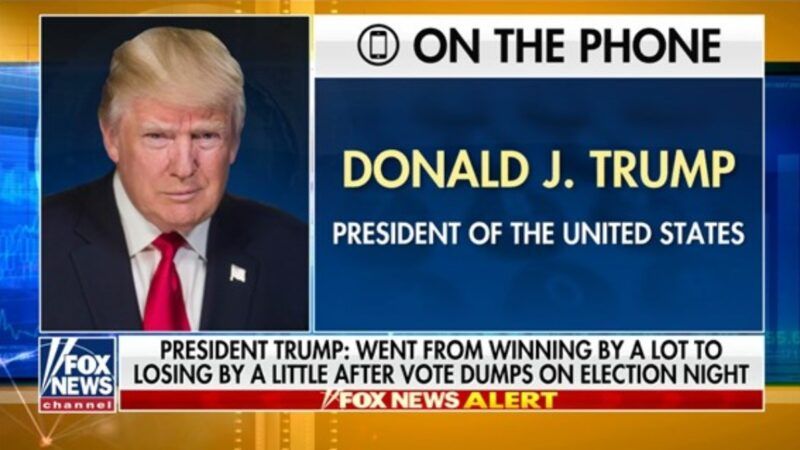

In his first TV interview since the presidential election, Donald Trump spoke to Fox News host Maria Bartiromo on Sunday morning, reiterating his unsubstantiated claim that vote counting was "rigged" to ensure Joe Biden's victory. Although Bartiromo began by inviting the president to "go through the facts" that support his allegations of systematic election fraud, he presented no real evidence, and Bartiromo did not press him to do so.

Instead Bartiriomo seemed to accept the president's claims at face value. "This is disgusting!" she said. "And we cannot allow America's election to be corrupted."

Any mildly skeptical person would have seen several opportunities for follow-up questions. "This election was a fraud," Trump said. "It was a rigged election." How so? "We had glitches where they moved thousands of votes from my account to Biden's account," he asserted. "They're not glitches. They're theft. They're fraud—absolute fraud."

Trump was repeating a story about fraud-facilitating voting machines that has been repeatedly debunked. "To our collective knowledge," a group of 59 computer scientists and election security experts said in an open letter published earlier this month, "no credible evidence has been put forth that supports a conclusion that the 2020 election outcome in any state has been altered through technical compromise." Trump's own Department of Homeland Security called the 2020 election "the most secure in American history," saying, "There is no evidence that any voting system deleted or lost votes, changed votes, or was in any way compromised."

In addition to claiming that voting machines were rigged, Trump said large numbers of fraudulent ballots mysteriously arrived at counting locations to save the day for Biden. "This election was over, and then they did dumps…big, massive dumps in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and all over," he said. "If you take a look at just about every state that we're talking about, every swing state that we're talking about…they did these massive dumps of votes. And all of a sudden, I went from winning by a lot to losing by a little….They started just doing ballot after ballot very quickly and just checking the Biden name on top. " This is another claim that the Trump campaign has failed to substantiate in court. "They backdated all these ballots that came in," Trump said, referring to yet another accusation that did not pan out.

Trump also asserted that "there are a lot of dead people that so-called voted in this election." Such cases, which typically involve people who mail absentee ballots on behalf of recently deceased spouses, are "exceedingly rare," FactCheck.org found. More often, purported examples of dead voters turn out to be mistakes—confusing a father and son with similar names, for instance. Sometimes people who cast votes by mail die before Election Day. "Every once in a while, it turns out that someone votes in the name of someone who's passed away," Justin Levitt, a voting fraud expert at Loyola Law School, told FactCheck.org. "A handful of votes in a sea of millions. It's not OK, but it doesn't swing results."

Trump expressed disappointment that the Department of Justice and the FBI had not taken his allegations more seriously, saying "maybe they're involved." If so, they would join a long list of alleged conspirators, including Democratic and Republican election officials, the Biden campaign, Dominion Voting Systems, George Soros, the Clinton Foundation, and the Venezuelan, Cuban, and Chinese governments, not to mention the Republican members of Congress, Trump-friendly news outlets, and Republican-nominated judges who have been skeptical of the president's claims about election fraud.

Again and again, post-election lawsuits filed by the Trump campaign have failed to specifically allege the sort of massive fraud that could have changed the outcome. Trump complained that some of those lawsuits have been dismissed for lack of standing, meaning the campaign failed to show that it had suffered an "injury in fact" caused by the defendants that would be addressed by the remedy it sought. "They say you don't have standing," Trump told Bartiromo. "You mean as president of the United States, I don't have standing. What kind of a court system is this?"

As U.S. District Judge Matthew Brann explained when he rejected the Trump campaign's attempt to block certification of Pennsylvania's election results, it's the kind of court system that is empowered to act only when it is presented with "cases" or "controversies." To satisfy that requirement, Brann noted, "a plaintiff must establish that they have standing," which is "an 'irreducible constitutional minimum,' without which a federal court lacks jurisdiction to rule on the merits of an action."

The Trump campaign, joined by two voters, challenged Pennsylvania's policy regarding technical errors in absentee ballots. Some counties, following advice from Secretary of the Commonwealth Kathy Boockvar, gave voters a chance to "cure" those errors, while other counties did not. The campaign and the voters argued that the uneven application of that policy violated the 14th Amendment's guarantee of equal protection.

Brann found that the two voters, whose ballots were rejected by counties that did not give them a chance to fix their mistakes, could not show that the injury they asserted—invalidation of their votes—was caused by the parties they sued: Boockvar and seven counties that allowed curing. Furthermore, the remedy they sought—preventing certification of millions of other people's votes—would not have corrected the injury.

As for the Trump campaign, Brann said, the issue of standing "is particularly nebulous because neither in the [first amended complaint] nor in its briefing does the Trump Campaign clearly assert what its alleged injury is. Instead, the Court was required to embark on an extensive project of examining almost every case cited to by Plaintiffs to piece together the theory of standing as to this Plaintiff."

Brann considered two possibilities: "associational standing" and "competitive standing." He concluded that neither applied in this case.

Associational standing requires that an organization's members "would otherwise have standing to sue in their own right." Since the voters who joined the lawsuit did not have standing to sue Boockvar and the seven counties, Brann said, the campaign could not meet that prong of the test.

Competitive standing, according to case law from the 9th Circuit on which the Trump campaign relied, "is the notion that 'a candidate or his political party has

standing to challenge the inclusion of an allegedly ineligible rival on the ballot, on

the theory that doing so hurts the candidate's or party's own chances of prevailing

in the election.'" That description did not apply to this case either.

Although Brann concluded that the plaintiffs did not have standing to sue, he considered their equal protection claims while deciding whether to dismiss the lawsuit. "Even if Plaintiffs had standing, they fail to state an equal-protection claim," he said. "The general gist of their claims is that Secretary Boockvar, by failing to prohibit counties from implementing a notice-and-cure policy, and Defendant Counties, by adopting such a policy, have created a 'standardless' system and thus unconstitutionally discriminated against Individual Plaintiffs. Though Plaintiffs do not articulate why, they also assert that this has unconstitutionally discriminated against the Trump Campaign."

The two voters' equal protection claims ran into the same problem as their argument for standing: The defendants were not responsible for rejecting their ballots. "Because Defendants' conduct 'imposes no burden' on Individual Plaintiffs' right to vote, their equal-protection claim is subject to rational basis review," Brann said. "Defendant Counties, by implementing a notice-and-cure procedure, have in fact lifted a burden on the right to vote, even if only for those who live in those counties. Expanding the right to vote for some residents of a state does not burden the rights of others."

Brann concluded that Pennsylvania's notice-and-cure policy easily satisfied the highly deferential rational basis test, because "it is perfectly rational for a state to provide counties discretion to notify voters that they may cure procedurally defective mail-in ballots." Although "states may not discriminatorily sanction procedures that are likely to burden some persons' right to vote more than others," he said, "they need not expand the right to vote in perfect uniformity."

Regarding the Trump campaign, Brann wrote, "they do not allege that Secretary Boockvar's guidance differed from county to county, or that Secretary Boockvar told some counties to cure ballots and others not to. That some counties may have chosen to implement the guidance (or not), or to implement it differently, does not constitute an equal-protection violation."

The campaign also complained that election officials in some counties kept poll watchers unreasonably far from the vote counting. But here, too, it failed to allege that the practice discriminated against Republicans. "Plaintiffs fail to plausibly plead that there was 'uneven treatment' of Trump and Biden watchers and representatives," Brann said.

Contrary to Trump's implication in the Fox News interview, then, Brann did consider the plausibility of the campaign's equal protection claims, and he found them wanting. So did the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit in a ruling it issued on Friday. "The Campaign cannot win this lawsuit," the unanimous three-judge panel said in a scathing opinion written by a Trump appointee. "The Campaign's claims have no merit."

Show Comments (245)