How Will Bitcoin Lead to More Freedom?

The 1987 debate that foreshadowed the divide in today's cryptocurrency community

Katie Haun has one of bitcoin's most improbable conversion stories. As an attorney at the U.S. Department of Justice, she prosecuted the two corrupt federal agents working the Silk Road case and created the federal government's first cryptocurrency task force. "I'm the prosecutor who helped put some of the earliest bitcoin criminals in jail," she boasted in a 2018 speech.

But while learning about bitcoin as a crime fighter, it dawned on her "how profoundly this technology could change how we do all sorts of things." Haun is now a general partner at the venture capital fund Andreessen Horowitz, or a16z, where she co-leads its crypto funds with over $350 million raised since 2018. The firm is betting on blockchain as a new computing platform that will, among other things, create a decentralized financial system and fulfill the web's original promise as an open network controlled by its users.

Blockchain computing "feels like the early days of the internet, web 2.0, or smartphones all over again," according to a16z's crypto thesis. Haun also sits on the board of the nonprofit organization overseeing Facebook's cryptocurrency project Libra. At a 2019 congressional hearing, David Marcus, head of the company's blockchain group, assured lawmakers, "Let me be clear and unambiguous: Facebook will not offer the Libra digital currency until we have fully addressed regulators' concerns and received appropriate approvals."

In their embrace of regulation, Haun and Marcus are at one extreme of the cryptocurrency community; on the other end, are the so-called bitcoin maximalists who have a name for projects like Libra: "shitcoin."

"I would not be interested in bitcoin if governments didn't want to ban it," the software developer Pierre Rochard tweeted in 2017.

In a December 2019 essay titled "Cryptocurrency Is Most Useful for Breaking Laws and Social Constructs, Open Money Initiative Founder Jill Carlson wrote that cryptocurrency wasn't designed to solve "mainstream problems." It's a tool used by "freedom fighters and terrorists, by journalists and dissidents, by scammers and black market dealers," by "sex workers" or people "procuring drugs on the internet"—the type of person Katie Haun once worked to put in jail. Bitcoin maximalists, like Rochard, believe that governments will eventually attempt to ban bitcoin because it's destined to replace fiat money, which will, among other things, eliminate their power to print money to finance the welfare-warfare state.

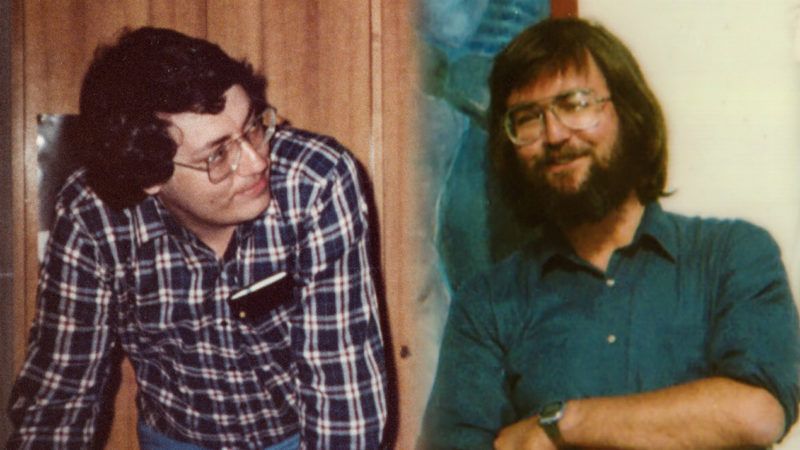

The divide over whether this technology is a tool for changing society by working within the system or by disrupting it from the outside predates the invention of bitcoin by a few decades. It traces back to a 1987 debate between the physicist Timothy C. May and the economist and entrepreneur Phil Salin, two early internet visionaries, whose difference of opinion laid the groundwork for the "cypherpunk" movement—a community of computer scientists, mathematicians, hackers, and avid science fiction readers whose work and writings influenced the creation of bitcoin, WikiLeaks, Tor, BitTorrent, and more. (Reason recently published a four-part documentary series on the cypherpunk movement.)

The bitcoin maximalists often use the "shitcoin" moniker to refer to cryptocurrency projects that are outright scams, technologically flawed, or cheap imitations of Satoshi Nakamoto's invention, when in reality the world only needs one currency. Bitcoin, they maintain, is best understood as sound money, and Silicon Valley's infatuation with "blockchain technology" is "a great example of 'cargo cult science,'" as the economist Saifedean Ammous wrote in The Bitcoin Standard: The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking.

But the community's divide is also partly rooted in a disagreement over whether cryptocurrency is essentially a technology of resistance that derives value from being impervious to government interference and control, or whether it's a tool for transforming society from within, in which case government regulation won't sink the entire enterprise. A careful look at the debate that started with May and Salin in the 1980s helps us understand the best arguments of both sides.

BlackNet: 'A Technological Means of Undermining all Governments'

In 1987, before the launch of the World Wide Web, May and Salin were part of a small community of West Coast science fiction–obsessed technologists mulling the implications of a decentralized, global information network running on personal computers. It was clear to May and Salin that the internet would remake the world, but they disagreed on what kind of software would serve as the linchpin.

Salin saw technology as a way to gradually drive down the transaction costs that impede human activity, making it feasible to interact in ways that would otherwise be prohibitively expensive. "I'm interested in how to lower costs," Salin told Reason in 1984. "The Austrian [School of Economics] insight is that any industry run as a planned economy for any time should be fertile ground for an entrepreneur."

In 1986, he started the American Information Exchange, or AMIX, one of the first e-commerce startups. Salin, whose intellectual hero was the Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek, envisioned AMIX as a global marketplace for the buying and selling of local expertise that would enhance human cooperation and gradually replace central planning.

In a 1991 essay, Salin envisioned a "fluid, transaction-oriented market system, with two-way feedback" that could result in "crowding out monolithic, mostly government bureaucracies." The same language could be applied to many projects in the modern cryptocurrency space. Facebook's Libra, for example, promises to use blockchain technology to move money around the world in a manner that's "as easy and cost-effective" as "sending a message or sharing a photo." The project's backers maintain that enabling "frictionless payments" for the 1.7 billion people around the world without access to banking will do wonders for alleviating poverty. Those frictions are mostly created by government regulation; what's implicit in Facebook's pitch is that those rules will be gradually crowded out, though not overthrown.

After being introduced to Salin by his friend Chip Morningstar, a computer scientist, in December 1987, May drove out to Redwood City, California to meet Salin and hear his pitch for AMIX. He grasped the idea immediately, but it bored him. "People aren't going to be selling meaningless stuff, like surfboard recommendations," May recalled telling Salin.

May didn't think AMIX was a scam, like many modern cryptocurrency ventures that earn that descriptor shitcoin. But he was interested in upending society and didn't see how AMIX would have much of an impact.

May suggested to Salin that he reconceive of the project as an anonymous platform for selling company trade secrets, "such as plans for that B-1 Bomber or a process for a technology." In a thought experiment, May later called his idea "BlackNet," writing in a pretend advertisement for the service that it would turn "nation-states, export laws, patent laws, national security considerations and the like" into "relics of the pre-cyberspace era."

In a series of personal notes following his meeting with Salin, which May shared with Reason prior to his death in 2018, he mused that BlackNet was a "technological means of undermining all governments." Though some might say that "'it won't be allowed to happen' technology would 'probably make it inevitable,'" he wrote.

May's ideas about BlackNet evolved over the years. In 1986, a friend had given him a photocopy of Vernor Vinge's 1981 novella True Names, in which hackers inhabit a virtual world called the "Other Plane" where the government can't decipher their real identities. It had a big impact on May, who melded the "Other Plane" with "Galt's Gulch" from Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged, which was a safe haven for rational and productive people protected from government coercion and taxation by an invisible shield. Instead of the Colorado mountains, May's cyberspace Galt's Gulch would exist on the internet, with cryptography providing protective cover.

"Just as the technology of printing altered and reduced the power of medieval guilds and the social power structure," May wrote in his 1988 manifesto, "so too will cryptologic methods fundamentally alter the nature of corporations and of government interference in economic transactions."

Bitcoin isn't BlackNet or a Galt's Gulch in Cyberspace—it's a decentralized form of non-governmental money. But it's designed to be impervious to outside tampering so that the government can't destroy it or undermine its value, and is roughly in keeping with May's vision of an unstoppable technology. "The nature of sound money…lies precisely in the fact that no human is able to control it," Ammous wrote in The Bitcoin Standard. Bitcoin "exist[s] orthogonally to the law; there is virtually nothing that any government authority can do to affect or alter [its] operation."

The American Information Exchange: Exploiting the 'Grey Areas'

The computer scientist E. Dean Tribble, who worked with Salin at AMIX, calls May "the shock jock" of the cypherpunk movement. "BlackNet is not a goal," he says. "BlackNet is a negative consequence."

Morningstar, the pioneering computer scientist who Salin hired to oversee the building of AMIX, recalls his boss's skepticism of May's ideas about escaping "the strictures and dysfunction of the mainstream-governed world." The establishment "has had a long history of confronting new challenges and somehow having its way."

Salin died of cancer in 1991 at age 41. His friend and colleague Mark S. Miller, a computer scientist, would flesh out the case that technology impacts society by gradually transforming it from within. Miller drew an analogy to a genetic takeover in biology, in which an alternate way of doing things slowly takes the place of an existing paradigm.

Projects like AMIX, which was centrally controlled by a company, didn't need to be completely "incorruptible" to have an impact because of all the grey areas where regulation doesn't apply. Permissionless innovation pushes society in the direction of more freedom and decentralization. For example, "when people started doing credit card transactions over the internet, nobody knew if it was legal," Miller tells Reason, "but they just started doing it."

Miller doesn't consider Libra to be a worthless project despite Marcus' commitment to cooperate with regulators. Once it starts operating, Miller says, there could still be experimentation happening "at the margins." There could also be gateways to "trading between Libra and something permissionless," which would help expand the cryptocurrency space.

Miller's writings have often focused on how rules baked into computer code could replace aspects of the legal system. Along with K. Eric Drexler, the father of nanotechnology, he co-authored a series of papers applying economic insights to software design, which influenced the work of the computer scientist, legal scholar, and early cypherpunk Nick Szabo.

It was Szabo who coined the term "smart contracts"—self-executing arrangements written in code, and a common feature in today's cryptocurrency projects. Szabo analogized his concept to a vending machine: A buyer drops in a coin and a machine provides the candy bar. "The fundamental logic here is automating 'if-this-then-that' on a self-executing basis with finality," Szabo wrote. He also offered the example of a smart contract for auto repossession: "If the owner fails to make payments, the smart contract invokes the lien protocol, which returns control of the car keys to the bank."

A divide in the community over the definition of a smart contract also relates back to Salin's debate with May. Do smart contracts have to be shielded from third-party interference to be worthy of the name? What if a government regulator has the power to stick a hand into the metaphorical vending machine to stop the candy bar from dropping into the slot? Does that undermine the purpose of smart contracts?

Miller and Morningstar consider AMIX to be "possibly the first smart-contracting system ever created" because it used software to mediate transactions between two parties. Deals on AMIX combined a written component, like a traditional contract, and a self-executing component: once a buyer and seller agreed on a price for a service, payment would be carried out by software. If there was a dispute, it would be resolved by humans.

AMIX software ran on a central server, meaning the company or a government regulator could theoretically interfere with the execution of a sale. According to Morningstar and Miller, the potential for interference doesn't undermine the purpose of the smart contract.

"A smart contract that trusts a third party removes the killer feature of trustlessness," wrote Jimmy Song, a bitcoin maximalist and influential figure in the space, in his 2018 essay, "The Truth About Smart Contracts."

Song applies his critique to a popular crypto business model, which Miller has also written about: using smart contracts to trade physical assets, such as land. Countries like Sweden and Georgia have explored operating a land registry that uses blockchains and smart contracts. Szabo explored this idea in a 1998 paper that predated blockchains and bitcoin titled "Secure Property Titles with Owner Authority."

Physical assets are traded with smart contracts through what's called tokenization. A property is assigned a digital tag with a corresponding private key. A seller uses that key to transfer ownership to the buyer, much like a bitcoin transaction. The record of ownership is encoded into a blockchain, which is a type of shared public database, so all parties know that it hasn't been corrupted.

"There is an intractable problem in linking a digital to a physical asset whether it be fruit, cars or houses," Song wrote. It "suffers from the same trust problem as normal contracts" because "physical assets are regulated by the jurisdiction you happen to be in."

So if a judge refuses to honor that tokenized transaction, or a conqueror shows up at the door with an army, the smart contract will have accomplished nothing. "Ownership of the token cannot have dependencies outside of the smart contracting platform," wrote Song, who sees smart contracts as useful only in systems like bitcoin, where the digital token itself holds value.

Miller offered a rebuttal to this argument in a lecture titled, "Computer Security as the Future of Law" in 1997, predating Song's article by 21 years. He laid out a vision for a gradual takeover of the existing law by smart contracts. We live in a world where different systems of rules are layered on top of each other, he explained. When Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky played chess, they had to abide by the rules of the board, dictating, for example, that bishops can only move diagonally. They were simultaneously governed by another set of rules because the two men were "biological creatures…embedded in physics." A Macintosh operating system is another example of a system that imposes a set of rules spelled out in software embedded in another set of rules—i.e., legal strictures, physics, and biology.

The rules on these different layers impact each other. For example, the physical world and the legal world have distinct sets of rules, but in legal disputes "physical possession has extraordinary influence in the actual outcome of the dispute, even if abstractly the law would have it otherwise." If an object that belongs to you is in another person's house, taking them to court to get possession of that object is rarely worth the hassle.

AMIX integrated computer-mediated contracts and human negotiated contracts. It's true that humans, including government regulators, could override a transaction on AMIX, but for practical reasons that was unlikely to occur very often. Therefore, smart contracts on AMIX would have fulfilled their purpose in the vast majority of cases by reducing transaction costs with computer-mediated contracting.

Miller elaborated on this idea in a discussion of land registries in "The Digital Path: Smart Contracts and the Third World," a 2003 paper that he co-wrote with Marc Stiegler. It acknowledges that a smart contracting system, "unlike government-based title transfer," won't be "backed by a coercive enforcement apparatus," but the authors proposed various add ons to make it more likely that participants will "treat these titles as legitimate claims," including a community rating system, and video contracting—an idea first proposed by Szabo—in which a conversation is recorded testifying to the validity of the arrangement in question.

These tools don't guarantee that governments will honor and enforce smart contracts, but there's also a high cost to ignoring them. Szabo summed up this idea best in his 1998 paper: "While thugs can still take physical property by force, the continued existence of correct ownership records will remain a thorn in the side of usurping claimants."

Miller, Morningtar, and Tribble, who were involved with AMIX in the 1980s, have come together once again to try and make good on Salin's vision. Miller and Tribble co-founded a startup called Agoric, which seeks to build a secure smart-contracting system that could serve as the backbone of a more decentralized internet, luring some high-level computer scientists away from comfortable jobs at the biggest software companies in Silicon Valley.

May passed away suddenly in 2018 at age 66. In the months leading up to his death, he was feeling disgusted with the proliferation of cryptocurrency conferences and regulated blockchain ventures. "I think Satoshi would barf," he told CoinDesk. "Attempts to be 'regulatory-friendly' will likely kill the main uses for cryptocurrencies, which are NOT just 'another form of PayPal or Visa.'"

In May's view, society still faced a "fork in the road…freedom vs. permissioned and centralized systems." There are no grey areas.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

It won't, just like it hasn't. Next question.

Wrong. Everything which doesn't repress people leads to more freedom, simply by existing. A new flavor or PopTarts is more freedom. New forms of currency are more freedom.

I quit working at shoprite and now I make $65-85 per/h. How? I'm working online! My work didn't exactly make me happy so I decided to take a chance on something new…AMs after 4 years it was so hard to quit my day job but now I couldn't be happier.

Here’s what I do…>> Click here

Google is by and by paying $27485 to $29758 consistently for taking a shot at the web from home. Sdf I Abe have joined this action 2 months back and I have earned $31547 in my first month the from this action. I can say my life is improved completely! Take a gander at it

what I do……………………………Visit Here

I get paid more than $120 to $130 per hour for working online. I heard about this job 3 months ago and Amn after joining this i have earned easily $15k from this without having online working skills. This is what I do..... .Visit Here

Google is by and by paying $27485 to $29758 consistently for taking a shot at the web from home. I have joined NOW this action 2 months back and I have earned $31547 in my first month from this action. I can say my life is improved completely! Take a gander at it

what I do..................Click here

The argument is, It will destroy the inflationary portion of the warfare-welfare-surveilance state funding structure. And with that? It will destroy most everything government. Traditional taxes will continue to work in funding the government. But every deficit dollar will have to be funded by the free market with real interest rates. Taxing for the surveilance state with incometax raises will become much much harder. Impossible, seems to me. Atleast, that's the argument.

Google is by and by paying $27485 to $29658 consistently for taking a shot at the web from home. I have joined this action 2 months back and I have earned $31547 in my first month from this action. I can say my life is improved completely! Take a gander at it

what I do.....................................Click here

Google paid for all online work from home from $ 16,000 to $ 32,000 a month. The younger brother was out of work for three months and a month ago her check was $ 32475, working at home for 4 hours a day, and earning could be even bigger….So I started......Visit Here

I quit working at shop rite to work online and wit8h a little effort I easily bring in around $45 to 85 per/h. Without a doubt, this is the easiest and most financially rewarding job I’ve ever had. I actually started 6 months ago and this has totally changed my life.

For more details………………Visit Here

Google is by and by paying $27485 to $29758 consistently for taking a shot at the web from home. Sdh I have joined this action 2 months back and I have earned $31547 in my first month the from this action. I can say my life is improved completely! Take a gander at it

what I do………Visit Here

The problem I have with Bitcoin is its deflationary structure. The number of bitcoins that can be mined is capped, and it is getting harder and harder to mine them. I always try to emphasize how important price really is as a signal for parties to a transaction, and a deflationary currency causes weird behavior. Hoarding is the most obvious, but just think of long term employment. If I work for 1 BC this year, and my boss gives me a "raise" to .8 BC next year, how do I know how my standing is?

This ultimately will cause discontent around the currency. People already hate the "haves" who happen to already own land, or have savings- but at least those people have to keep working and reinvesting to keep up with inflation. With an inherently deflationary currency, the "haves" merely have to sit there and get rich because they were early into the market.

A currency that uses a trustless process to mint new coins as some sort of mineral, or production capacity is created would be more interesting, as it would scale with economic activity.

If I work for BC this year, and my boss gives me a “raise” to .8 BC next year, how do I know how my standing is?

These are complex subjects. In theory-- and this is 'theory', bitcoin would act kind of like gold. An ounce of gold in your pocket will buy more than it did a year ago. That's how gold works now.

With an inherently deflationary currency, the “haves” merely have to sit there and get rich because they were early into the market.

I can't help but wonder if there are parallels to the populist 'silverite' movement back in the day.

Gold and all commodities are too unstable to be good indicators of inflation or deflation.

I'm not sure if I agree with that or not.

Gold and silver rushes have changed prices.

Understood, but the price of gold was ostensibly changing throughout all of history, and yet gold was the principle form of currency right up until the late 20th century. I'm not a gold bug, but I definitely do not like the fiat currency system we have today, in how governments essentially drain the value out of your earnings before your very eyes via policy.

There was the bi-metallic problem, where silver and gold were used simultaneously for coinage; tr-metallic if you throw in copper pennies. Being different commodities, they fluctuated differently, and arbitragers took advantageous of that to melt down coins in one jurisdiction and sell them in another.

I despise fiat currencies too. But that doesn't make commodity currencies perfect. All currencies have defects, that's why you need a free market in currencies.

i don't disagree that we need a free market in currencies, I'm just suspicious of digital currencies as being viable for global transactions. Especially when we saw the speed at which we saw Bitcoin morph from its initial stated intent to its current understanding. Specifically, Bitcoin was anonymous. Whoops, no it it wasn't. Bitcoin was going to be usable for buying Hershey bars in the convenience store. Whoops, too much computing in the blockchain making transactions too slow and cumbersome. Then came the wild price fluctuations. Then it came to the point where no one could really articulate WHAT bitcoin was- aside from settling on it being a 'store of value' (again, not unlike gold).

Google is by and by paying $27485 to $29758 consistently for taking a shot at the web from home. Sdf I have joined this action 2 months back and I have earned $31547 in my first month the from this action. I can say my life is improved completely! Take a gander at it

what I do………………………………Visit Here

Yeah but crypto can be shaved indefinitely. There is no theoretical limit to the number of decimal points you can divide it by. An atom of gold is not too useful though!

That doesn't change the fact that today, an hour of my labor is worth 1 Bitcoin, and in 2 years it will be worth .5 Bitcoins. A completely arbitrary currency shortage is fucking with the price of my labor, which makes the job of price signaling more difficult for people. This makes markets less efficient.

It's very interesting theoretically. I like the Bitcoin joke when the price was spiking:

I can't remember it exactly, but it went something like:

Have you seen the price of Bitcoin?

Yeah, it's $12,975

I'd like a bitcoin for my birthday!

I'm not spending $17,845 on your birthday present!

I quit working at shop rite and now I make $65-85 per/h. How? I’m working online! My work didn’t qwe exactly make me happy so I decided to take a chance on something new after 4 years it was so hard to quit my day job but now I couldn’t be happier So i try use.

Here’s what I do…>>Easy work to Home

It doesn't work as a currency when the volatility is what is it. That's why it isn't one and won't be used as one. At the moment, it's the best treasury asset. Denominate your wages in USD, it's fine. Only a 10% or w/e yearly haircut in purchasing power. When a billion people have some BTC? The BTC purchasing power will be the smoothest thing on the planets history. And growing. It's the fiat currency that will be in the volatility hell, a'la Venezuela, Zimbabwe and Lebanon. At some point you will be able contract wages in BTC. Not yet.

There are also inflationary cryptocurrencies like Monero. Of course, the inflation schedule is still set by consensus, not by a backroom deal.

"These are complex subjects. In theory– and this is ‘theory’, bitcoin would act kind of like gold. An ounce of gold in your pocket will buy more than it did a year ago. That’s how gold works now."

Certainly. That is what happens in deflation. You have to spend more labor to get that bit coin, but the store will have to give you more bananas before you will relinquish it.

My point is that deflationary crunches like this are bad. Whenever you have something messing with price signals other than the supply and demand of the goods being traded (like the supply of the currency), it leads to inefficient market clearing, right? That's why mandated price ceilings cause shortages.

An ideal currency would grow at a rate roughly following economic activity. Personally, I would link a currency to electricity generation, since that is pretty much the foundation of all economic activity.

There's nothing inherently deflationary about a currency with a fixed quantity. Particularly not with Bitcoin since the incentive to keep processing transactions remains long after all the Bitcoins have been mined. Lots of people still hold them, and the fees to process transactions are fluid and set by a bid system.

They are inherently deflationary. As the demand for Bitcoins increases, the supply is constrained. Why would demand increase? A growing economy. More people are doing work, more resources are being untapped, productivity is making work more efficient. Thus more transactions are taking place.

If your labor today buys you 1 bitcoin with X demand on bitcoin, then in one year when 2X demand is being placed on bitcoins, you will have to spend MORE labor to get it- i.e. the same labor is worth a fraction.

Oh now I get it. You don't know the difference between nominal and real prices.

Rich don't have cash. They have assets. The inflation appreciates the assets of the rich and destroy purchasing power of the middle and lower class wages and saving ability. In inflation, the poor get poorer, and the rich get richer as matter of course.

Now, if you get wages in BTC? And that BTC is in deflation? He can afford more goods and services the next year. The poor gets richer, as a matter of course. He gets the ability to grow his portion of the BTC. The opposite of inflation. And that is possibly the most best important thing in the history of the planet.

Also, it destroys the business cycle. And the warfare-welfare state. Your quibles about the distribution is childish envy.

Bitcoin "self-corrects" to it's human *value*. In my book that's not a bad thing like you're pretending it is. Something more *valuable* to humans today should be worth more that's WHY people are drawn to what people need, WHY creativity grows, WHY produce is made. It's called "reality" of supply and demand.

The USD "self-corrects" too by becoming utterly worthless. The problem with that is it's made worthless by the "power" of government politics which essentially is the result of stealing labor/savings/investments already earned by working people. Who gets all the "printed" money and what did they do to *earn* it?

You need to look at money be it crypto or not as nothing but a representation of value (by whom). If you create value for mankind it shouldn't be vulnerable to 3rd party stealing. If the value of what you own becomes "more valuable" then the reality of it is it is more valuable to the people. If the value of what you own is "trash" then the reality of it is it is "trash". That's just how it is.

re: "a deflationary currency causes weird behavior"

Only to someone ignorant of economic history. For most of the time since the invention of money, currency was deflationary to one degree or another. Look, for example, at price trends in the 17th and 18th centuries. You say that it causes "hoarding". Most people call that "saving" and consider it a good thing.

You are only uncomfortable with it because it seems like a novel, even unthinkable concept to someone who grew up in the era of inflationary currencies.

It's worth remembering why governments let their currencies inflate. Governments are primarily debtors - and inflation is strongly favorable to debtors.

By the way, we should also note that there is a very good paper addressing the theoretical limits on bitcoin. Eventually, the value of mining new coins will be balanced by the costs of the electricity necessary to do so. Along with some other assumptions that seemed reasonable to me, that sets a theoretical maximum value of bitcoin in the $40k range (stable value, not spot fluctuations).

Assuming that analysis is true, bitcoin will eventually stop being deflationary but should never become inflationary. Again, a radical concept to someone who only has experience with inflationary fiat currencies but not so radical if you study economic history.

But while learning about bitcoin as a crime fighter, it dawned on her "how profoundly this technology could change how we do all sorts of things."

Did she start her own website where anything can be exchanged for bitcoin?

Make 6,000 dollar to 8,000 dollar A Month Online With No Prior Experience Or Skills Required. Be Your Own Boss AndChoose Your Own Work Hours.Thanks A lot Here>>> Read More.

BlackNet: 'A Technological Means of Undermining all Governments'

In 2020, this means something entirely different.

What I want, what I think would be much better than what we have now, is private currencies. They used to be a thing, and reliable. Statists like to recoil in horror at the complexity, ignoring that in colonial America, England had forbidden use of English currency in the colonies. Not that it stopped use of its currency, but it did mean that colonists used any currency they could -- Spanish, French, Dutch, wampum, hogsheads of tobacco and other commodities -- and by Gum! if the colonists could keep track of all those fluid relative values, when communication from north to south could take a month, and communication across the Atlantic could take several months, and neither was reliable, well hell we wouldn't have any problem today with instant reliable communication and calculators on every phone.

The competition would be intense and keep everybody in line. It would make all government currencies look like the frauds they are.

My thoughts on this is that the world was far less globalized and economies moved much more slowly than they do now. When it took four months to get silks from the Orient to the New World, things like price fluctuations and inflation weren't major factors.

My problem with cryptocurrencies is mainly that there are potentially infinite numbers of them that can be released. With that, the trust people would have to place their life savings in a stable one becomes very touchy. The analogue I sometimes make is Social Networking sites. Imagine if you'd have put all your money into Friendster. Then everyone stampeded to MySpace. Then Facebook... then...

Did you know that prior to the Fed's creation in 1913, banks used to publicize their stability? They advertised who was on their boards of directors, what there reserves were. Obviously this was mostly meant for rich people who had big deposits, but poor people paid attention to it also, and banks did try to attract small depositors; there were too many to ignore.

All those cryptocurrencies would try to accumulate the same kind of back story, bragging about their security, who founded them, who controlled them. Most people wouldn't know enough to tell them apart and would stick with the big names with a history.

I am aware of that and that system isn't in place any more, probably for the same reasons cryptocurrencies would go through a 'wild west' period and then get pulled into a regulatory structure resulting in just 'one'... that was controlled by the feds.

There's nothing stopping private cryptocurrencies from engaging in that NOW. But as you see, it's very difficult to transact in cryptocurrencies, so Bitcoin has instead devolved into a kind of 'store of value'- not unlike gold.

I have my specific concerns about bitcoin and the 'store of value' proposition, and the Bitcoin evangelists haven't done much to allay my concerns what with their shifting goalposts on what Bitcoin was supposed to be vs what it is.

I think the theory of Ethereum is where the breakthrough lies.

Is Ethereum the one that uses Bitcoin as its standard basis?

It is its own currency, so I don't think so. But it allows much more expressive smart contracts than Bitcoin.

Right, these are the kinds of technological improvements that would make a blockchain currency more "viable" to transact in... but again, those iterations are potentially infinite. At some point, you could see a new digital currency on the market every day. I do believe in the 'wisdom of crowds'-- to a limited degree. I also believe in the 'madness of crowds' as well. Both things are true. Crowds can work out for themselves what systems are good, and crowds can also whip themselves into irrational frenzies that cause sudden collapses in systems.

It's a good point and a valid criticism. I think along the lines of what Á àß äẞç ãþÇđ âÞ¢Đæ ǎB€Ðëf ảhf was saying, it does actually stabilize.

There have been numerous forks from Bitcoin (and you can make one yourself now, as you're probably aware). But none of them have anywhere near the market cap of BTC. I think the incentive to stay together on a single chain ends up being greater than the incentive to just willy-nilly split into a million new chains. Of course, some people will do just that. Maybe one of them will result in something much better, and it will take over. Most will probably not, but most are also ignored and have little impact on the major cryptocurrencies.

Ethereum is the one that is already being used in some places (apparently) for validating title to real estate and other contracts that don't directly relate to currency.

But as you see, it’s very difficult to transact in cryptocurrencies

I agree, there are a lot of challenges to overcome before something like Bitcoin can be used on a day-to-day basis. Some of the solutions may involve partial centralization, others may involve genuine technological breakthroughs. I would say that because of the uncertainty around all of it, it's not something that I'd tell family and friends to dump money into--at least money they aren't willing to potentially lose.

But at the same time, the fact that it isn't currently practical on a day-to-day basis shouldn't stop the most creative among us from trying to make it so.

But at the same time, the fact that it isn’t currently practical on a day-to-day basis shouldn’t stop the most creative among us from trying to make it so.

No, nothing I say that's critical of Bitcoin or digital currencies in general should be construed to suggest everyone should just give up.

Well, since they mention it in the article, let me just point out a shocking truth about this 'Libertarian" website: you cannot access it with Tor. WTF.

Clarify-- access the comments with Tor.

Very cool, very accurate and agreeable to even harcore btc maximalist like myself. Except for the alleged Jimmy Song rebuttal. It doesn't work. He didn't know the cost of blockchain. Putting Uber reviews on blockchain doesn't produce any value that justifies the cost of absolute global ledger the likes of bitcoin. The most saleable asset is the money. Money is the one winner takes all form of game. All altcoins are a distraction.

Bitcoin or some successor might be useful someday, but now it's just an investment scam based on the bigger idiot theory. It isn't a useful medium of exchange or store of value because of the insane price fluctuations. The only reason it's worth anything at all is that it can be sold for real money, i.e. dollars or euros

I am creating an honest wage from home 3000 Dollars/week , that is wonderful, below a year agone i used to be unemployed during a atrocious economy. I convey God on a daily basis i used to be endowed these directions and currently it’s my duty to pay it forward and share it with everybody,….... Read More

Easy and easy job on-line from home. begin obtaining paid weekly quite $4k by simply doing this simple home job. I actually have created $4823 last week from this simple job....Visit here to earn thousands of dollars

This Jim Epstein is just another shit-eating tech journalist cut from the mold of all other shit-eating tech journalists. The tech journalist breed evolved from the sportswriter, the similarities should be clear.

The principles of tech journalism are simple: revisionist history to create comic-book quality heroes, clickbait claims, absolutely zero critical analysis, and hagiography instead of biography. This article is complete garbage, a perfect reflection of its author.

I'm glad she acknowledged the monstrous premise of this otherwise good comedy. A couple breaks up, so they decide to divide up their infant twins -- so each girl will never see the other parent, her sister, or any of her other relatives again? Or even know she has a sister? Just as in the original version of this movie, the real villains a re clearly both parents........ Read More

I earned $4500 last month by working online just for 4 to 6 hours on my laptop and this was so easy that i myself could not believe before working on this Website. If You too want to earn such a big amount of money then come and join us.….So I started…Click here.

I am creating an honest wage from home 3000 Dollars/week , that is wonderful, below a year agone i used to be unemployed during a atrocious economy. I convey God on a daily basis i used to be endowed these directions and currently it’s my duty to pay it forward and share it with everybody….. Read More

Awesome content. a got a know a lot.

here's my blog:- https://thepassivelion.com

Bitcoin can bring the world currency under one supreme control.

I support cryptocurrencies very much.

Best Fitness Bands

The currency markets are the backbone of the global economy and the banks are riding it like a bucking bronco.

Best Fitness Bands

For the first time in digital history, we have what can make us send and receive money cross-boarder without the need to trust any middleman, attach our personal details, and also be able to track it. I think that is freedom. Though the privacy freedom is gradually dying due to centralization in the space, Bitcoinmix, and several other platforms are helping out with that . You can till send Bitcoin or crypto around and not get tracked to you. That is freedom imo.

There is much more possibility of taking a relief payday loan to improve your overall financial situation. The government should consider more drastic measures to help its citizens because we will not survive the second wave of coronavirus as good as the first one. Some people at directloantransfer are willing to help