Amy Coney Barrett and the Problem of Conservative Judicial Deference

Reviewing the record of the SCOTUS shortlister.

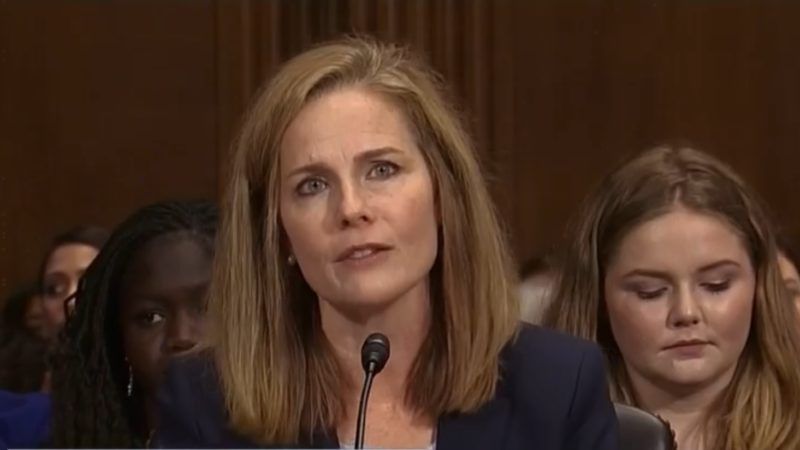

Judge Amy Coney Barrett of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit is reportedly at the top of President Donald Trump's shortlist of candidates to replace the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the U.S. Supreme Court. A former Notre Dame law professor, Barrett is a popular and respected figure in conservative circles. But any conservative or libertarian who hopes to see the federal courts pay greater heed to the original meaning of the 14th Amendment is likely to be troubled by some of Barrett's writings on judicial deference and economic liberty.

In 1938 the Supreme Court concocted a bifurcated approach to judicial review that treats some constitutional rights as more equal than others. If a law or regulation infringes on a right that the Court has deemed fundamental (such as freedom of speech or the right to vote), the Court said in United States v. Carolene Products Co., the judiciary should presume that law or regulation to be unconstitutional and subject it to "more exacting judicial scrutiny." By contrast, in cases dealing with "regulatory legislation affecting ordinary commercial transactions," Carolene Products stated, "the existence of facts supporting the legislative judgment is to be presumed." In other words, judges are supposed to tip the scales in favor of lawmakers when economic liberty might be at stake.

Now known as the rational-basis test, this rubber stamp approach has led to some truly dreadful judgments. Take Goesaert v. Cleary (1948), in which the Supreme Court upheld a Michigan law forbidding women from working as bartenders unless they were "the wife or daughter of the male owner." Valentine Goesaert, who owned a bar in Dearborn, fought for her right to tend bar in her own establishment. She lost thanks to rational-basis deference.

"We cannot cross-examine either actually or argumentatively the mind of Michigan legislators nor question their motives," declared Justice Felix Frankfurter. "Since the line they have drawn is not without a basis in reason," he wrote, invoking the rational-basis test, "we cannot give ear to the suggestion that the real impulse behind this legislation was an unchivalrous desire of male bartenders to try to monopolize the calling." Needless to say, the ban on female bartenders served no legitimate public health or safety purpose.

Rational-basis deference was also at the center of the federal district court ruling in Niang v. Carroll (2016). At issue was a Missouri law that made it a crime to offer African-style hair braiding services without a cosmetology license. That slip of government paper did not come cheap. In addition to paying thousands of dollars in fees, would-be African-style hair braiders had to complete over 1,500 hours of state-sanctioned education. What is worse, none of Missouri's licensed cosmetology schools actually offered any training in African-style hair braiding. Once again, the regulation at issue served no legitimate public health or safety purpose.

But none of that mattered to Judge John M. Bodenhausen of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri, who let the preposterous law stand. "This case," Bodenhausen declared, "illustrates the great deference that federal courts must show to government regulations under the rational basis standard."

Amy Coney Barrett has written in defense of the rational-basis standard. "Highly deferential judicial review reflects the judgment that a more searching inquiry would pull judges into terrain they are not good at navigating," Barrett wrote in a 2017 article for Constitutional Commentary. "The current, deferential regime reflects humility about the capacity of judges to evaluate the soundness of scientific and economic claims." According to Barrett, "deferential judicial review of run-of-the-mill legislation" is defensible on the grounds that such judicial deference "is consistent with the reality that the harm inflicted by the Supreme Court's erroneous interference in the democratic process is harder to remedy than the harm inflicted by an ill-advised statute."

The late Antonin Scalia once defended judicial deference in similar terms, arguing in a 1984 speech that "the position the Supreme Court has arrived at is good—or at least that the suggestion that it change its position is even worse." According to Scalia, the best approach in economic cases was for the courts to adopt an across-the-board stance of judicial pacifism. "In the long run, and perhaps even in the short run," Scalia maintained, "the reinforcement of mistaken and unconstitutional perceptions of the role of the courts in our system far outweighs whatever evils may have accrued from undue judicial abstention in the economic field."

The problem with the Scalia-Barrett view is that it runs counter to the text and history of the 14th Amendment, which was written, ratified, and originally understood to protect (among other rights) the right to economic liberty. In the words of Rep. John Bingham (R), the Ohio congressman who served as the principal author of Section One of the 14th Amendment in 1866, "the provisions of the Constitution guaranteeing rights, privileges, and immunities" includes "the constitutional liberty…to work in an honest calling and contribute by your toil in some sort to the support of yourself, to the support of your fellow men, and to be secure in the enjoyment of the fruits of your toil."

Put differently, if the federal courts had followed the 14th Amendment—rather than the judicially invented rational-basis test—then a bar owner's right to tend bar in her own establishment and an African-style hair braider's right to earn a living would have been rightfully secured against arbitrary and unnecessary government interference.

If Amy Coney Barrett is nominated to replace Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, I hope that someone on the Senate Judiciary Committee will ask her whether she thinks that rational-basis deference can be reconciled with the original meaning of the 14th Amendment.

Show Comments (98)