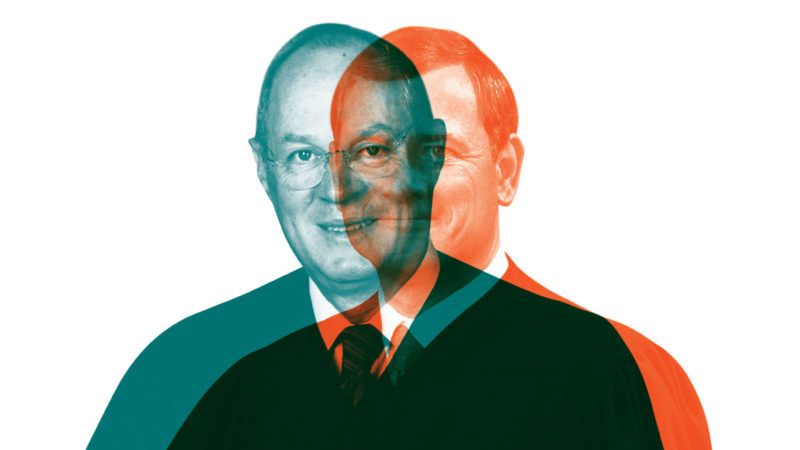

Is John Roberts the New Anthony Kennedy?

Like it or not, this is the Roberts Court now.

When Anthony Kennedy retired from the U.S. Supreme Court in 2018, he enjoyed the distinction of having been denounced by every major political faction in the country. For conservatives, Kennedy was the activist judge who "invented" a right to gay marriage. For progressives, he was the corporate shill who authored Citizens United. For libertarians, he was guilty of both enabling eminent domain abuse and squashing the rights of local medical marijuana users in favor of a national drug control scheme. At one point or another, everybody had cause to hate him.

Is John Roberts the new Kennedy? As the Supreme Court's 2019–2020 term came to its dramatic close in July, the current chief justice not only solidified his role as a swing voter in highly charged cases but managed to annoy practically everybody along the way.

Will the religious right ever forgive Roberts for siding with the Court's Democratic appointees to strike down an anti-abortion law? In Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt (2016), the chief justice dissented when the Court overturned a Texas statute that required abortion providers to have admitting privileges at local hospitals. But in this last term's June Medical Services v. Russo, Roberts did the opposite, concurring in a decision that voided a nearly identical abortion regulation from Louisiana.

"I joined the dissent in Whole Woman's Health and continue to believe that the case was wrongly decided," Roberts wrote in a lone concurrence. However, "stare decisis requires us, absent special circumstances, to treat like cases alike," he continued. "The Louisiana law imposes a burden on access to abortion just as severe as that imposed by the Texas law, for the same reasons. Therefore Louisiana's law cannot stand under our precedents."

Plenty of progressives praised Roberts for that. But their cheers turned to jeers when he delivered a huge victory just one day later for both school choice and religious liberty advocates. "A State need not subsidize private education," Roberts wrote in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue. "But once a State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious." The Court has "long recognized the rights of parents to direct 'the religious upbringing' of their children," he observed. "Many parents exercise that right by sending their children to religious schools, a choice protected by the Constitution."

And then there was Seila Law v. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, in which the chief justice led the Court in declaring the single-director structure of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) to be unconstitutional. "The CFPB Director has no boss, peers, or voters to report to," Roberts pointed out. "Yet the Director wields vast rulemaking, enforcement, and adjudicatory authority over a significant portion of the U.S. economy. The question before us is whether this arrangement violates the Constitution's separation of powers." Roberts held that it did. Not exactly a happy outcome for supporters of the administrative state.

Libertarians, of course, were criticizing Roberts before it was cool. In 2012's National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, Roberts characterized his vote to uphold the Affordable Care Act as a demonstration of conservative judicial restraint. "It is not our job to protect the people from the consequences of their political choices," he wrote, invoking as a role model the early 20th century jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., who once declared, "If my fellow citizens want to go to Hell I will help them. It's my job." That deferential approach is the antithesis of the libertarian legal movement's vision of the judiciary as a strong bulwark against overreaching government.

On many of the biggest and most contentious legal issues of our time, the chief justice stands at the center of the SCOTUS storm. Like it or not, this is the Roberts Court now.

Show Comments (65)