The COVID-19 Recovery Is Starting. Extending 'Bonus' Unemployment Benefits Will Slow It.

If Congress extends boosted temporary unemployment benefits into early 2021, nearly five out of every six beneficiaries would be earning more money by not working.

If Congress extends boosted temporary unemployment benefits into early 2021, nearly five out of every six beneficiaries would be earning more money by not working—likely slowing the labor force's recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

That's according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which on Thursday sent a letter to Sen. Chuck Grassley (R–Iowa) outlining some of the potential consequences if Congress votes to extend those boosted unemployment benefits through the end of January. As part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act passed in March, Congress added an additional $600 to unemployment checks above and beyond whatever state-level payments were granted to laid-off workers. That provision is set to expire on July 31, but the House passed a $3.5 trillion stimulus bill last month that would extend those payments for six additional months. The Senate has yet to take it up.

From the start, there have been worries about the economic incentives created by the boosted unemployment payments. Though unemployment benefits vary from state to state, the federal "bonus" meant the average worker could qualify for as much as $900 per week—well over $20 an hour, if you assume a standard 40-hour workweek. Because these payments are delivered via the unemployment insurance system, they are contingent on not holding a job—they are distinct from the $1,200 stimulus checks that were sent to all Americans.

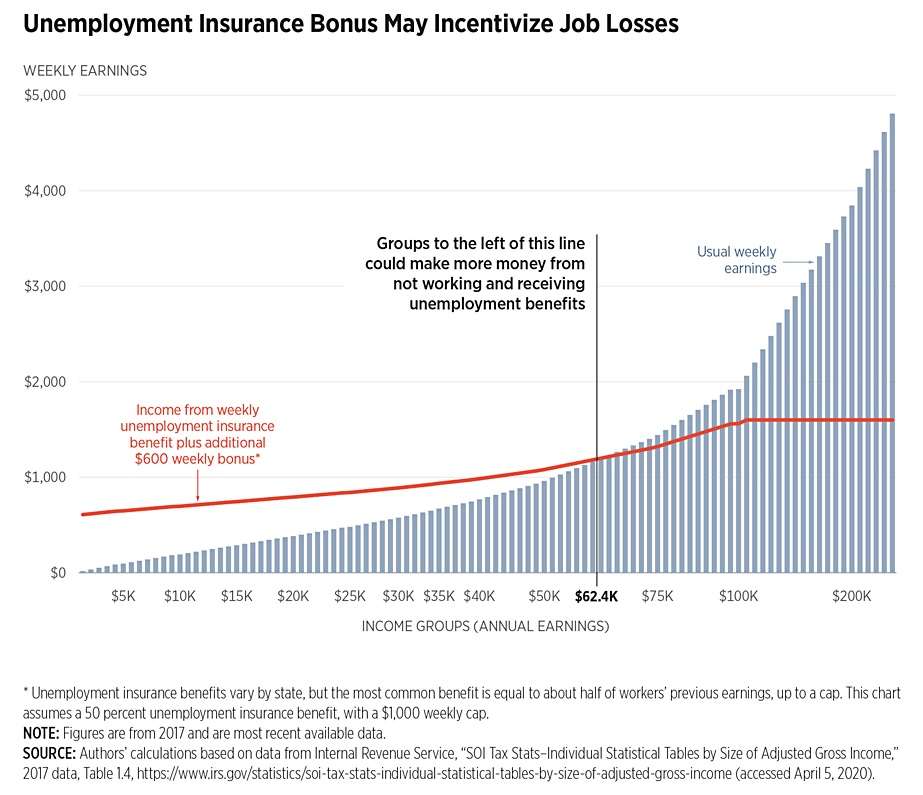

Economists at the conservative Heritage Foundation calculated that workers earning less than $62,000 annually would end up making more money on unemployment.

Paying people not to work might have made sense temporarily because governments were literally telling people it was illegal to go to work. But as the economy transitions into a recovery period, some businesses are reporting that it is difficult to bring workers back or make necessary hires for reopening.

Again, incentives matter. "The additional $600 per week in benefits decreases the incentive to work more for people who expect to have lower earnings than it does for people who expect to have higher earnings because that additional amount is a larger percentage of lower-earning workers' potential earnings," the CBO letter explains.

Friday's announcement that the unemployment rate fell in May to 13.3 percent after peaking at 14.7 percent in April is another factor for lawmakers to consider. The threat of COVID-19 has not passed—more than 100,000 Americans have died from the disease—and returning to full employment or a fully functioning economy is probably not possible in the short-term. Still, the unemployment rate being lower than many experts anticipated seems to be a sign that markets are finding ways to navigate both the horrors of the pandemic and the barriers erected by governments to stop the spread.

Like with the lockdowns themselves, the next phase of the coronavirus safety net requires scalpels, not hammers. Congress could set aside some funding to be used if citywide or statewide lockdowns are necessary in some places due to COVID-19 flare-ups, perhaps. But extending the federal unemployment boost for all workers seems unnecessary and perhaps even counter-productive.

The CBO's analysis makes clear that there are several trade-offs for Congress to consider.

"An extension of the additional benefits would boost the overall demand for goods and services, which would tend to increase output and employment," CBO director Phillip Swagel wrote to Grassley on Thursday. "That extension would also weaken incentives to work as people compared the benefits available during unemployment to their potential earnings, and those weakened incentives would in turn tend to decrease output and employment."

Continuing to put more money in unemployed workers' pockets, in other words, would juice demand in the short-term but would drag the jobs recovery into next year and generally slow the economy. The Heritage Foundation analysis from April projects that the added $600 benefit would reduce the size of the economy by more than $950 billion due to unemployed workers taking longer to return to their jobs.

The merits of the temporary unemployment boost through the end of July are debatable. Extending them into next year would deliberately kneecap any chance of a speedy recovery.

Show Comments (68)