The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Making Sense of the Votes in the Ramos v. Louisiana Majority (Updated)

Ramos was not nearly as fractured as Apodaca, but the Court is still splintered on the value of precedent

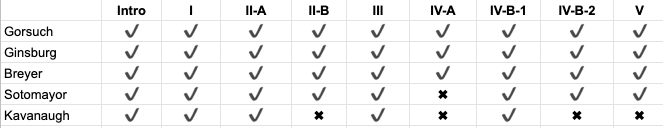

Today the Supreme Court decided Ramos v. Louisiana. (Eugene and Jon blogged about it earlier). The votes are very, very complicated:

GORSUCH, J., announced the judgment of the Court, and delivered the opinion of the Court with respect to Parts I, II–A, III, and IV–B–1, in which GINSBURG, BREYER, SOTOMAYOR, and KAVANAUGH, JJ., joined, an opinion with respect to Parts II–B, IV–B–2, and V, in which GINSBURG, BREYER, and SOTOMAYOR, JJ., joined, and an opinion with respect to Part IV–A, in which GINSBURG and BREYER, JJ., joined. SOTOMAYOR, J., filed an opinion concurring as to all but Part IV–A. KAVANAUGH, J., filed an opinion concurring in part. THOMAS, J., filed an opinion concurring in the judgment. ALITO, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which ROBERTS, C. J., joined, and in which KAGAN, J., joined as to all but Part III–D.

Justice Kavanaugh offered this explanation of the breakdown:

As noted above, I join the introduction and Parts I, II–A, III, and IV–B–1 of JUSTICE GORSUCH's opinion for the Court. The remainder of JUSTICE GORSUCH's opinion does not command a majority. That point is important with respect to Part IV–A, which only three Justices have joined. It appears that six Justices of the Court treat the result in Apodaca as a precedent and therefore do not subscribe to the analysis in Part IV–A of JUSTICE GORSUCH's opinion.

And Kavanaugh adds this count in another footnote:

As I read the Court's various opinions today, six Justices treat the result in Apodaca as a precedent for purposes of stare decisis analysis. A different group of six Justices concludes that Apodaca should be and is overruled.

Justice Alito offers this breakdown in his dissent:

Three Justices join the principal opinion in its entirety. Two Justices do not join Part IV–A, but each of these Justices takes a position not embraced by portions of the principal opinion that they join. See ante, at 2 (SOTOMAYOR, J., concurring in part) (disavowing principal opinion's criticism of Justice White's Apodaca opinion as "functionalist"); ante, at 15–17 (KAVANAUGH, J., concurring in part) (opining that the decision in this case does not apply on collateral review). And JUSTICE THOMAS would decide the case on entirely different grounds and thus concurs only in the judgment.

This graph (as best as I can tell) charts the votes in the majority.

I will update the post as I make my way through the 87-page opinion.

Update: The remainder of this post explains the complicated breakdown of the Ramos majority.

Part II-B

Justices Gorsuch, Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor joined Part II-B . This brief section (pp. 9-11 of the slip opinion) tries to make sense of Apodaca v. Oregon:

So what could we possibly describe as the "holding" of Apodaca?

Really, no one has found a way to make sense of it. In later cases, this Court has labeled Apodaca an "exception," "unusual," and in any event "not an endorsement" of JusticePowell's view of incorporation.34 At the same time, we have continued to recognize the historical need for unanimity.35 We've been studiously ambiguous, even inconsistent, about what Apodaca might mean.

Justice Kavanaugh did not join Part II-B.

Part IV-A

Justices Gorsuch, Ginsburg, and Breyer joined Part IV-A (pp. 16-20 of the slip opinion). This section responds to Justice Alito's dissent. He wrote:

I begin with the question whether Apodaca was a precedent at all. It is remarkable that it is even necessary to address this question, but in Part IV–A of the principalopinion, three Justices take the position that Apodaca was never a precedent. The only truly fitting response to thisargument is: "Really?"

The troika responds:

If Louisiana's path to an affirmance is a difficult one, the dissent's is trickier still. The dissent doesn't dispute that the Sixth Amendment protects the right to a unanimous jury verdict, or that the Fourteenth Amendment extends this right to state-court trials. But, it insists, we must affirm Mr. Ramos's conviction anyway. Why? Because the doctrine of stare decisis supposedly commands it. There are two independent reasons why that answer falls short.

Gorsuch also argues that a ninth justice, in a plurality case, should not be able to single-handedly overrule precedent:

Admittedly, this example comes from our imagination.It has to, because no case has before suggested that a singleJustice may overrule precedent. But if the Court were to embrace the dissent's view of stare decisis, it would not stay imaginary for long. Every occasion on which the Court is evenly split would present an opportunity for single Justices to overturn precedent to bind future majorities. Rather than advancing the goals of predictability and reliance lying behind the doctrine of stare decisis, such an approach would impair them

Justices Sotomayor and Kavanaugh did not join Part IV-A, for different reasons.

Justice Sotomayor wrote in her concurrence:

I agree with most of the Court's rationale, and so I join all but Part IV–A of its opinion. I write separately, however, to underscore three points. First, overruling precedent here is not only warranted, but compelled. Second, the interests at stake point far more clearly to that outcome than those in other recent cases. And finally, the racially biased origins of the Louisiana and Oregon laws uniquely matter here.

Judge Kavanaugh "wr[o]te separately to explain [his] view of how stare decisis applies to this case."

He grounded this view in Article III itself:

The Framers of our Constitution understood that the doctrine of stare decisis is part of the "judicial Power" and rooted in Article III of the Constitution.

This statement echoes remarks he gave during his confirmation hearing:

Precedent is not just a judicial policy. Precedent comes right from Article III of the Constitution. Article III refers to the "judicial power." What does that mean? Precedent is rooted right into the Constitution itself.

Kavanaugh identifies "three broad considerations that, in my view, can help guide the inquiry and help determine what constitutes a 'special justification' or 'strong grounds' to overrule a prior constitutional decision.

- First, is the prior decision not just wrong, but grievously or egregiously wrong?

-

Second, has the prior decision caused significant negative jurisprudential or real-world consequences?

-

Third, would overruling the prior decision unduly upset reliance interests?

In short, the first consideration requires inquiry into how wrong the precedent is as a matter of law. The second and third considerations together demand, in Justice Jackson's words, a "sober appraisal of the disadvantages of the innovation as well as those of the questioned case, a weighing of practical effects of one against the other."

Part IV-B-2

Justices Gorsuch, Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor joined Part IV-B-2 (pp. 23-26). Justice Kavanaugh did not join Part IV-B-2. Justice Kavanaugh did join Part IV-B-1. This section talks about the precedential value of Apodaca. First, the majority attacks its reasoning. Second, the Court says it is inconsistent with other decisions. Third, Justice Gorsuch rejects one of the state's reliance interests: the need to retry approximately 1,000 defendants. Part IV-B-2 turns to a second reliance interest:

The second and related reliance interest the dissent seizes upon involves the interest Louisiana and Oregon have in the security of their final criminal judgments. In light of our decision today, the dissent worries that defendants whose appeals are already complete might seek to challenge their nonunanimous convictions through collateral (i.e., habeas) review.

Gorsuch rejects this concern. He writes that "Under Teague v. Lane, newly recognized rules of criminal procedure do not normally apply in collateral review."

Justice Kavanaugh does not join this discussion of Teague, but also finds that the rule should not be applied retroactively:

Teague recognizes only two exceptions to that general habeas non-retroactivity principle: "if (1) the rule is substantive or (2) the rule is a 'watershed rul[e] of criminal procedure' implicating the fundamental fairness and accuracy of the criminal proceeding." Whorton v. Bockting, 549 U. S. 406, 416 (2007) (internal quotation marks omitted). The new rule announced today—namely, that state criminal juries must be unanimous—does not fall within either of those two narrow Teague exceptions and therefore, as a matter of federal law, should not apply retroactively on habeas corpus review.

I'm not sure why Justice Kavanaugh dissented from IV-B-2. He seems to agree with the outcome, but perhaps not the analysis. [Update: On further reflection, I see that Kavanaugh expressly rejects Teague, but Gorsuch is a bit cagey.]

Part V

Justices Gorsuch, Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor joined Part V. This concluding paragraph appears at p. 26:

On what ground would anyone have us leave Mr. Ramos in prison for the rest of his life? Not a single Member of this Court is prepared to say Louisiana secured his conviction constitutionally under the Sixth Amendment. No one before us suggests that the error was harmless. Louisiana does not claim precedent commands an affirmance. In the end, the best anyone can seem to muster against Mr. Ramos is that, if we dared to admit in his case what we all know to be true about the Sixth Amendment, we might have to say the same in some others. But where is the justice in that? Every judge must learn to live with the fact he or she will make some mistakes; it comes with the territory. But it is something else entirely to perpetuate something we all know to be wrong only because we fear the consequences of being right. The judgment of the Court of Appeals is

Reversed.

Justice Kavanaugh did not join Part V.

Show Comments (38)