The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Making Sense of the Votes in the Ramos v. Louisiana Majority (Updated)

Ramos was not nearly as fractured as Apodaca, but the Court is still splintered on the value of precedent

Today the Supreme Court decided Ramos v. Louisiana. (Eugene and Jon blogged about it earlier). The votes are very, very complicated:

GORSUCH, J., announced the judgment of the Court, and delivered the opinion of the Court with respect to Parts I, II–A, III, and IV–B–1, in which GINSBURG, BREYER, SOTOMAYOR, and KAVANAUGH, JJ., joined, an opinion with respect to Parts II–B, IV–B–2, and V, in which GINSBURG, BREYER, and SOTOMAYOR, JJ., joined, and an opinion with respect to Part IV–A, in which GINSBURG and BREYER, JJ., joined. SOTOMAYOR, J., filed an opinion concurring as to all but Part IV–A. KAVANAUGH, J., filed an opinion concurring in part. THOMAS, J., filed an opinion concurring in the judgment. ALITO, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which ROBERTS, C. J., joined, and in which KAGAN, J., joined as to all but Part III–D.

Justice Kavanaugh offered this explanation of the breakdown:

As noted above, I join the introduction and Parts I, II–A, III, and IV–B–1 of JUSTICE GORSUCH's opinion for the Court. The remainder of JUSTICE GORSUCH's opinion does not command a majority. That point is important with respect to Part IV–A, which only three Justices have joined. It appears that six Justices of the Court treat the result in Apodaca as a precedent and therefore do not subscribe to the analysis in Part IV–A of JUSTICE GORSUCH's opinion.

And Kavanaugh adds this count in another footnote:

As I read the Court's various opinions today, six Justices treat the result in Apodaca as a precedent for purposes of stare decisis analysis. A different group of six Justices concludes that Apodaca should be and is overruled.

Justice Alito offers this breakdown in his dissent:

Three Justices join the principal opinion in its entirety. Two Justices do not join Part IV–A, but each of these Justices takes a position not embraced by portions of the principal opinion that they join. See ante, at 2 (SOTOMAYOR, J., concurring in part) (disavowing principal opinion's criticism of Justice White's Apodaca opinion as "functionalist"); ante, at 15–17 (KAVANAUGH, J., concurring in part) (opining that the decision in this case does not apply on collateral review). And JUSTICE THOMAS would decide the case on entirely different grounds and thus concurs only in the judgment.

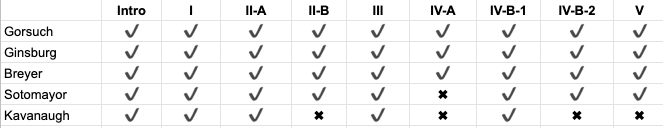

This graph (as best as I can tell) charts the votes in the majority.

I will update the post as I make my way through the 87-page opinion.

Update: The remainder of this post explains the complicated breakdown of the Ramos majority.

Part II-B

Justices Gorsuch, Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor joined Part II-B . This brief section (pp. 9-11 of the slip opinion) tries to make sense of Apodaca v. Oregon:

So what could we possibly describe as the "holding" of Apodaca?

Really, no one has found a way to make sense of it. In later cases, this Court has labeled Apodaca an "exception," "unusual," and in any event "not an endorsement" of JusticePowell's view of incorporation.34 At the same time, we have continued to recognize the historical need for unanimity.35 We've been studiously ambiguous, even inconsistent, about what Apodaca might mean.

Justice Kavanaugh did not join Part II-B.

Part IV-A

Justices Gorsuch, Ginsburg, and Breyer joined Part IV-A (pp. 16-20 of the slip opinion). This section responds to Justice Alito's dissent. He wrote:

I begin with the question whether Apodaca was a precedent at all. It is remarkable that it is even necessary to address this question, but in Part IV–A of the principalopinion, three Justices take the position that Apodaca was never a precedent. The only truly fitting response to thisargument is: "Really?"

The troika responds:

If Louisiana's path to an affirmance is a difficult one, the dissent's is trickier still. The dissent doesn't dispute that the Sixth Amendment protects the right to a unanimous jury verdict, or that the Fourteenth Amendment extends this right to state-court trials. But, it insists, we must affirm Mr. Ramos's conviction anyway. Why? Because the doctrine of stare decisis supposedly commands it. There are two independent reasons why that answer falls short.

Gorsuch also argues that a ninth justice, in a plurality case, should not be able to single-handedly overrule precedent:

Admittedly, this example comes from our imagination.It has to, because no case has before suggested that a singleJustice may overrule precedent. But if the Court were to embrace the dissent's view of stare decisis, it would not stay imaginary for long. Every occasion on which the Court is evenly split would present an opportunity for single Justices to overturn precedent to bind future majorities. Rather than advancing the goals of predictability and reliance lying behind the doctrine of stare decisis, such an approach would impair them

Justices Sotomayor and Kavanaugh did not join Part IV-A, for different reasons.

Justice Sotomayor wrote in her concurrence:

I agree with most of the Court's rationale, and so I join all but Part IV–A of its opinion. I write separately, however, to underscore three points. First, overruling precedent here is not only warranted, but compelled. Second, the interests at stake point far more clearly to that outcome than those in other recent cases. And finally, the racially biased origins of the Louisiana and Oregon laws uniquely matter here.

Judge Kavanaugh "wr[o]te separately to explain [his] view of how stare decisis applies to this case."

He grounded this view in Article III itself:

The Framers of our Constitution understood that the doctrine of stare decisis is part of the "judicial Power" and rooted in Article III of the Constitution.

This statement echoes remarks he gave during his confirmation hearing:

Precedent is not just a judicial policy. Precedent comes right from Article III of the Constitution. Article III refers to the "judicial power." What does that mean? Precedent is rooted right into the Constitution itself.

Kavanaugh identifies "three broad considerations that, in my view, can help guide the inquiry and help determine what constitutes a 'special justification' or 'strong grounds' to overrule a prior constitutional decision.

- First, is the prior decision not just wrong, but grievously or egregiously wrong?

-

Second, has the prior decision caused significant negative jurisprudential or real-world consequences?

-

Third, would overruling the prior decision unduly upset reliance interests?

In short, the first consideration requires inquiry into how wrong the precedent is as a matter of law. The second and third considerations together demand, in Justice Jackson's words, a "sober appraisal of the disadvantages of the innovation as well as those of the questioned case, a weighing of practical effects of one against the other."

Part IV-B-2

Justices Gorsuch, Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor joined Part IV-B-2 (pp. 23-26). Justice Kavanaugh did not join Part IV-B-2. Justice Kavanaugh did join Part IV-B-1. This section talks about the precedential value of Apodaca. First, the majority attacks its reasoning. Second, the Court says it is inconsistent with other decisions. Third, Justice Gorsuch rejects one of the state's reliance interests: the need to retry approximately 1,000 defendants. Part IV-B-2 turns to a second reliance interest:

The second and related reliance interest the dissent seizes upon involves the interest Louisiana and Oregon have in the security of their final criminal judgments. In light of our decision today, the dissent worries that defendants whose appeals are already complete might seek to challenge their nonunanimous convictions through collateral (i.e., habeas) review.

Gorsuch rejects this concern. He writes that "Under Teague v. Lane, newly recognized rules of criminal procedure do not normally apply in collateral review."

Justice Kavanaugh does not join this discussion of Teague, but also finds that the rule should not be applied retroactively:

Teague recognizes only two exceptions to that general habeas non-retroactivity principle: "if (1) the rule is substantive or (2) the rule is a 'watershed rul[e] of criminal procedure' implicating the fundamental fairness and accuracy of the criminal proceeding." Whorton v. Bockting, 549 U. S. 406, 416 (2007) (internal quotation marks omitted). The new rule announced today—namely, that state criminal juries must be unanimous—does not fall within either of those two narrow Teague exceptions and therefore, as a matter of federal law, should not apply retroactively on habeas corpus review.

I'm not sure why Justice Kavanaugh dissented from IV-B-2. He seems to agree with the outcome, but perhaps not the analysis. [Update: On further reflection, I see that Kavanaugh expressly rejects Teague, but Gorsuch is a bit cagey.]

Part V

Justices Gorsuch, Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor joined Part V. This concluding paragraph appears at p. 26:

On what ground would anyone have us leave Mr. Ramos in prison for the rest of his life? Not a single Member of this Court is prepared to say Louisiana secured his conviction constitutionally under the Sixth Amendment. No one before us suggests that the error was harmless. Louisiana does not claim precedent commands an affirmance. In the end, the best anyone can seem to muster against Mr. Ramos is that, if we dared to admit in his case what we all know to be true about the Sixth Amendment, we might have to say the same in some others. But where is the justice in that? Every judge must learn to live with the fact he or she will make some mistakes; it comes with the territory. But it is something else entirely to perpetuate something we all know to be wrong only because we fear the consequences of being right. The judgment of the Court of Appeals is

Reversed.

Justice Kavanaugh did not join Part V.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Heck with that, they could issue a per curiam opinion stating all the points where a majority is able to agree, and explain in plain English where they can't agree, then do the concurrences.

"We hold that the 6th and 14th Amendments require unanimous criminal juries. [1972 case] is overruled. Remanded for new trial.

We cannot agree on anything else. The following are some personal opinions of justices, of no precedential value."

Much more honest.

They seem to agree that this will not be retroactive. For some definitions of retroactive.

What this tells me is that SCOTUS is nowhere near as ideologically divided on a left/right axis as many would have us believe.

Or, perhaps, that the issues of today can't be divided along such an axis as a lot of people seem to think they can.

The other question -- and I'm wondering if that's addressed here -- is how Louisiana is unique in having a legal system based more on the Napoleonic Code than the British Common Law.

Now this may have evolved to the point where it has become more of a distinction than a difference, much like how we only have 46 "States" (MA, PA, VA, & KY are Commonwealths). Or it may not.

I need to read more about the civil law system. It would be interesting to see whether any aspects of Louisiana's civil law system are in tension with the Court's view of the 14th amendment

The obvious possibility would be the civil jury trial right: the Supreme Court said that Louisiana's system was fine in Walker v. Saudi et, 92 U.S. 90 (1875), but that seems to be at least in tension with this holding. (It's worth noting, however, that the civil adjudication systems in lots of other states would also have Seventh Amendment problems, and for all I know Louisiana doesn't even use the same system that it did in the 19th century.)

The civil law system doesn't matter as much as it does in the criminal law context where most states base their law on some kind of code rather than the common law. It matters far more in civil cases (hence why it is called civil law).

You have to look under the hood. The majority agreed that they had to ditch a 48-year-old precedent, that itself was badly fractured and poorly reasoned.

But the reasoning to apply here -- and arguments about stare decisis and incorporation of the Bill of Rights in the 14th Amendment -- have ramifications in other cases. These arguments are a forecast of future cases to come, including hot-button issues like abortion.

Yep.

What it tells me is that originalism is not inherently conservative or liberal. It's the only principled way to resolve an issue like this.

Folks: Ramos was really a proxy battle for the forthcoming challenge to Roe/Casey. That’s why you saw such strange fractures and alignments — the Justices were all laying down markers for how they viewed stare decisis, in preparation for the forthcoming Roe/Casey challenge. You saw the exact same thing thirty years ago in the dry personal jurisdiction case of Burnham v. Superior Court (Justices laying down markers on how they viewed due process, in preparation for Casey).

That's how I'm thinking, but that I suspect that folks will be surprised in the outcome. It won't be a party-line vote.

I would not be surprised to see RBG to say that abortion is an issue that should be regulated by the political process and hence the state -- she's as much said that in speeches.

"I would not be surprised to see RBG to say that abortion is an issue that should be regulated by the political process and hence the state — she’s as much said that in speeches."

Really?

"“I would not be surprised to see RBG to say that abortion is an issue that should be regulated by the political process"

What is the maximum negative number? Then you have the likelihood of her voting that way.

SEE: https://www.law.uchicago.edu/news/justice-ruth-bader-ginsburg-offers-critique-roe-v-wade-during-law-school-visit

Also her WaPo interview in 2014.

I'd be VERY surprised for her to rule that way. VERY.

"It won’t be a party-line vote."

Well, one party will be unanimous.

The nominal majority party probably won't be.

But if they are, it'd be all in good faith.

Unlike your implications about the liberals.

How much money would you like to stake on that?

If there are genuinely six votes for the earlier decision as precedent and six different ones to overrule the precedent, the former is dicta, as the latter is the only proposition necessary for the order of the holding. (Anyone voting to overrule a precedent is presumably even more willing to vote that way absent precedent.)

So if a group is sending someone to order and pick up a pizza, and of my eight friends, four think that anchovies aren't necessary for a good pizza, and one thinks that the pizzeria doesn't carry anchovies (which she loves), what reasoning lies behind our decision to not order anchovies? Is the absent-anchovy theory a narrower form of anchovy-aversion? The ideas are simply incoherent, because they say different things about the world. There is no narrower ground -- the lone vote is an island, not part of the main. Each proposition has two parts (1) there exists Anchovy (2) which is necessary for good pizza. One faction accepts (1) and rejects (2), the other the converse. No proposition can be formed other than the material rejection of the anchovy, and a court is bound by the rationale behind the decision, not (like a legislature) the decision itself.

The majority/plurality/severalty says that the reason to disregard is that Powell couldn't make a previously foreclosed position narrowest ground. Disagree. No prior holding required that the court reject every possible instance of two-track incorporation in order to reach the holding -- the courts pronouncements of absolute identity between state and federal rights are dicta, with the binding holding being the facts before them at the time. Powell was free to conclude that since England had just done away with unanimity, such things might not be beyond the pale. Now, as with judicial review, we're left with the idea that the colonies are more in line with Coke and Blackstone than those other folks who speak the tongue that Shakespeare spake.

It's an intriguing possibility.

Mr. D.

Brennan and Marshall were on the right side of history in Apodaca . . . as usual.

The conservatives of that day, not so much . . . also as usual.

To me, this is the sort of result America gets when the Court is making up the law as they go along. Each 'judge-made law' ruling made up of dicta makes the next one even more complicated to parse. Take, for example, the Court on capital punishment. Incomprehensible because it is not based on text, but personal ethics.

The irony should be lost on no one that Gorsuch is the one writing this opinion that is senseless to his colleagues left and right. Judicial philosophy only goes so far, no matter how many books about it a Justice writes.

The 6th and 14th Amendments are silent on the issue of jury unanimity. The legislatures may scramble to catch up with court rulings. But how many laws made jury verdicts unanimous before the first such judge-made law?

According to the opinion, at least six of the early state constitutions expressly required unanimous verdicts, and the others did so in practice.

At any rate, do you think there are any limitations to the Sixth Amendments jury trial requirement, beyond that the jury be impartial and come from the correct district? In your view, would a state violate the jury trial right by providing for trials by a "jury" of one person? Could a state provide that only judges were eligible to serve as jurors? Or perhaps only police officers?

Gorsuch probably got stuck with this opinion by a senior justice. Probably lost a bet.

More likely was the "shyte detail" that junior members of any organization often get stuck with.

Someone had to do it, and he was junior...

The Framers of our Constitution understood that the doctrine of stare decisis is part of the "judicial Power" and rooted in Article III of the Constitution.

This statement echoes remarks he gave during his confirmation hearing:

Precedent is not just a judicial policy. Precedent comes right from Article III of the Constitution. Article III refers to the "judicial power." What does that mean? Precedent is rooted right into the Constitution itself.

Kavanaugh is 100 percent right about this.

I'm reading the opinion and this is admittedly a rabbit trail, but when discussing the potential cost of this decision, Gorsuch cites briefs claiming that in 2018, there were 673 felony jury trials in Oregon. Oregon's population is about 4.2 million and only 673 felony jury trials? That is shameful. Far too many plea bargains and resolutions without trials.

Oregon also seems to have a fairly low rate of felony case filings for its population. (About 26,000 in 2018, compared to about 42, 000 in Kentucky.) There were also 283 felony bench trials, meaning that about 3.3% of felony cases went to a trial of some kind, which doesn't seem crazy to me. (Unfortunately trial data for other years isn't available online, as far as I can tell, so it's hard to say whether those numbers are typical or not.)

Not crazy in terms of current practice, but crazy in terms of, they're intimidating that many people into just pleading by various means.

It means they've arranged things so that most of the time they don't have to prove their case. NOT good.

Since this opinion did not gather 5 votes, does that mean it is not a precedent?

The parts of the opinion that gathered five votes are the opinion of the court and constitute binding precedent. The three sections that didn't (II-B, IV-A, IV-B-2, and V) are not.

*four sections, of course.

0r is it like Baake????

No, it's not like Bakke.

Really wish Gorsuch could have pulled together a majority for the part of his opinion clarifying Marks. I'm dealing with several circuit court decisions right now that, in my opinion, misapply Marks and it would have been nice if the Supreme Court had finally taken up that issue. No single Supreme Court justice's idiosyncratic views should establish precedent for the Court, especially when those idiosyncratic views are inconsistent with prior precedent.

One aspect not commented on thusfar. As a layperson, I appreciate very much Justice Gorsuch's writing style. It is clear, to the point, and understandable by anyone with a high school education (assuming you paid attention in high school). It is not written in ivory tower prose.

That last paragraph in Part V was magnificent. It laid everything bare.

Really? I find his affected folksiness to be off-putting, and I also find his tone tends to have an air of condescending smugnesss that rubs me the wrong way, even when I agree with him. (I also find his use of footnote citations infuriating.) Part V exemplifies this for me, and I commend Kavanaugh for deliberately not joining it.

I'd consider Kagan and Roberts the best writers on the court by far. You then have a long drop to Alito and Gorsuch, followed by Thomas and Ginsburg, with Breyer and Sotomayor rounding out the bottom. (I don't feel like I've read enough Kavanaugh to rank him.)