Trump's School Lunch Changes Lead to a Pointless Food Fight

"It's unconscionable that the Trump administration would do the bidding of the potato and junk food industries," noted one critic. But Trump's changes are relatively minor.

In January, President Donald Trump's administration announced changes to the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National School Lunch Program, which was previously overhauled by former first lady Michelle Obama.

"The Occupant is trying to play petty with the food our babies eat," tweeted Rep. Ayanna Pressley (D–Mass.) in response to the changes. "Add it to the list affirming that the cruelty is the point with this White House."

Sam Kass, who served as executive director of Obama's Let's Move! obesity reduction program, proclaimed to The New York Times, "It's unconscionable that the Trump administration would do the bidding of the potato and junk food industries."

In truth, Trump's changes are relatively minor. They allow participating schools to more easily serve a la carte items, such as hamburgers, as snacks; they reduce the amount of fruit required at breakfast; and they change the types of vegetables required at lunch. Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue says these changes were made at the behest of school districts and could reduce food waste.

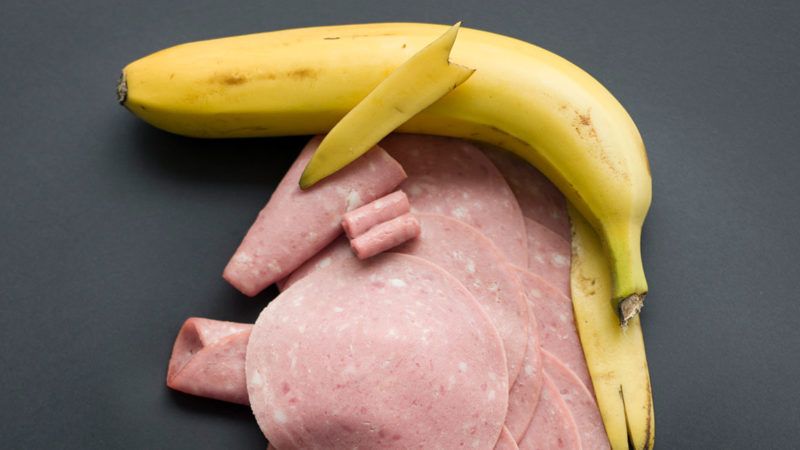

What's more, the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 that Democrats say Trump is undermining wasn't exactly built on flawless nutritional science. It required participating schools to serve low-fat or nonfat milk instead of whole milk, despite scant evidence that whole milk leads to weight gain. Complying with the fruit requirement sometimes saw schools giving low-income children two whole bananas with breakfast, despite the fact that starchy carbs are cheap and readily available to low-income households, while high-quality proteins are harder to afford for families relying on assistance.

The National School Lunch Program dates back to 1946 and is intended to make it easy for schools to feed their poorest students. Though Obama's changes sounded good on the surface, they may have contributed to a decline in participation in the program, which peaked in 2011 and has been dropping ever since. Strict school lunch requirements are futile if kids don't end up eating what's offered—something this administration aims to fix.

While you won't hear this from either side, the continued federalization of subsidized lunch is probably a bad idea. Washington has a long history of publishing unscientific and outdated nutrition science, and it takes years to revise itself. While many school districts may, in fact, need financial help to feed their poorest students, making that money contingent on adhering to federal menus is a recipe for conflict and political point-scoring rather than serious policymaking.

Show Comments (55)