2 Decades of Dubious Surveillance Will Make It Much Harder To Track COVID-19 Now

Government officials have only themselves to blame if citizens decline to share their information.

Would you tell an app on your phone if you tested positive for COVID-19 so that people who had been in close contact with you could be informed?

For many Americans, the answer would be yes, many emphatically so. But deep suspicion about who might see that information and how that information might be used to suppress civil liberties will push thousands, maybe even tens of thousands, of Americans to refuse.

Their refusal to participate might make it much harder to track the spread of the coronavirus and protect people from exposure. That's unfortunate, but that deep suspicion of how the government uses our private data from our phones and computers is justified by an entire post-9/11 regime of domestic surveillance that far too many government officials continue to defend.

Andrea O'Sullivan explained here at Reason how location technology on our phones could be used to help trace COVID-19 infections and how apps are playing an important role at stopping the spread in South Korea and China. Apple and Google are partnering up to host apps that will allow individuals around the world to participate. People who discover they've been infected with the coronavirus can inform the app, and the app will inform others who have come into close contact with them recently, letting them know they may have been exposed so that they can take proper precautions and self-isolate.

The way Apple and Google are approaching these tools is admirable, at least on paper. Participation will be voluntary. The tools won't actually collect identifiable information on location data. People who test positive will not be identified to Google or Apple or transmitted to health authorities. (Google explains how the location tracing will work here.)

But there's a lot of mistrust—and I don't just mean mistrust of Google and Apple. There's mistrust of governments, both authoritarian and democratic, who might be able to track citizens and collect data via phones. China is already doing this with its citizens. Let's not pretend that this is simply a tool of authoritarian regimes. After the passage of the PATRIOT Act, the National Security Agency (NSA) secretly implemented the collection and storage of mass amounts of Americans' phone and internet metadata, without a warrant or any real justification other than to search through it for potential terrorist plotting.

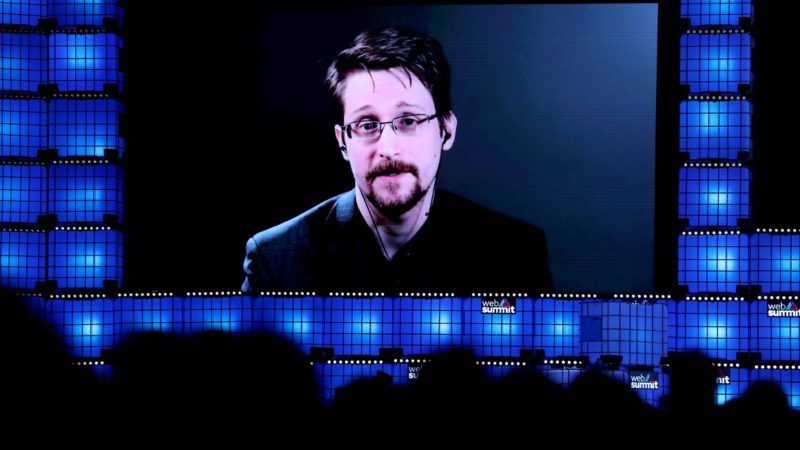

Edward Snowden revealed the extent of this surveillance to Americans almost seven years ago, and at the time, a significant number of bipartisan political leaders insisted that this surveillance, despite violating the Fourth Amendment rights of all Americans, was needed to protect us from violent terrorism. It was not. As the years went by, it became clear that this mass surveillance was not making us safer, nor was it an effective tool for fighting terrorism. The USA Freedom Act reformed the system to restrict how the data could be collected and accessed but also brought it out from the shadows and made it official policy. (The USA Freedom Act expired in March since Congress did not reach a compromise over renewing it as attention turned to the pandemic, a mostly unnoticed casualty of COVID-19.)

Now, Snowden warns that the same governments that used the fear of terrorism to justify massive domestic surveillance may do the same for the coronavirus. People may recall that Snowden was initially dismissed as a crank by a lot of people until the government was forced to acknowledge that much of what he'd revealed was actually true.

We already see examples of law enforcement agencies at home and abroad abusing their surveillance tools to try to exert authority over citizens instead of helping them. Drones can be a boon to police when searching for lost people or scoping out dangerous situations. But in England, one police department used them to snoop on and attempt to shame citizens who had gone to a park to exercise and be outdoors (none of these citizens appeared to be violating social distancing rules). In Kentucky, police are using license plate readers to force compliance with self-quarantine orders. This surveillance is not being used to collect information to track the coronavirus. It's being used to control people.

And so, if thousands of Americans (or Brits) refuse to assist public health agencies by opting into these apps, don't blame them. Blame the government officials who have reliably used every single crisis for the past two decades to insist they need to have access to more and more information about our private lives. Will Apple and Google even be able to keep their promises that the government can't access this private data, given that both politicians and the Department of Justice are trying to destroy encryption to make secret surveillance easier?

In all likelihood, I will download and participate in this app system when it's introduced. I live in Los Angeles in a neighborhood with a lot of families with older residents who are especially likely to have severe cases if they're exposed. But I wouldn't judge anybody who refuses to participate. The government already cried wolf. Now that they really need us to trust that they truly need to know where we are, they've already trained us not to believe them.

Show Comments (39)