Is the American Dream Dead?

When Americans feel like the future will be worse than the past, reactionary and socialist ideologies ascend.

Here are two stories about modern Americans' economic lives.

The first story is that the American Dream is dead. The cost of college is ballooning even as higher education becomes a prerequisite for an increasing proportion of white-collar jobs. Those jobs have become more important to the American middle class as manufacturing and many other forms of well-compensated blue-collar work disappear. The debt from obtaining this quasi-mandatory college education (especially at expensive, cut-throat elite schools where admission is statistically impossible) puts newly minted adults in a terrible position. They feel they cannot move forward with one of the major milestones of 20th century adulthood: homeownership. Nor can they afford to live in major cities with job growth, such as New York and San Francisco, where rents have been increasing and vacancy rates dropping for the last decade. Seventeen percent of adults say they cannot pay this month's bills in full. Feeling financially insecure, they defer childbearing, and when they do have kids they are stressed about how to pay for child care and education. Less-educated male wage earners have been hit hardest by these economic changes; as a result, they are struggling with unemployment, obesity, disability, suicide, and drug abuse. In extreme cases, this leads to "deaths of despair" and decreasing life expectancy. Some could be helped with medical interventions, but when they seek treatment, they're hit by a combination of rising health care costs (and attendant medical debt) and a confusingly opaque system. One-fourth of adults say they have forgone necessary care because they were unable to afford it. Government spending on health care, mostly for the elderly, is out of control, yet some elderly people are still choosing between filling their prescriptions and buying food. One-quarter of nonretired adults have no retirement savings or pension whatsoever. Oh, and now there's a global pandemic.

The second story is that modern Americans are living the dream. They have more education, bigger houses, greater employment options, and better stuff than ever before. Unemployment, which was just shy of 10 percent at the start of 2010, is now 3.6 percent. Real median household income recently hit a high of $62,000 per year. In February, Gallup reported that 90 percent of Americans say they are "satisfied with their personal lives." New homes in the United States are 1,000 square feet larger than they were in 1973; living space per person has doubled. Interest rates are low. More Americans than ever are obtaining college degrees, and those degrees are paying dividends: The lifetime net return for a typical college graduate is more than half a million dollars. Consumer goods overall are cheaper and higher-quality thanks to innovation and global trade, and per-capita expenditure on food has gone from more than 17 percent of disposable income in 1960 to just over 9 percent today. Health care is expensive, but 92 percent of Americans have insurance—and our ability to treat cancer, AIDS, and other diseases has improved tremendously. Zooming out, more people are healthy, well-fed, literate, and safe from physical violence than at almost any time in human history.

Both of these stories are basically true. Which one predominates in your thinking is a function of your temperament, your political persuasion, and your personal situation.

Market-minded optimists may be tempted to focus on the second story, especially if the goal is to fend off large interventions into the economy. The impulse is to say that the rumors of the death of the American Dream are greatly exaggerated and that people are simply mistaken about whether life is—on balance—worse in meaningful ways.

But it's important to take the first story seriously on its own terms, not least because it is the story that has completely dominated American electoral politics in 2020 on both the left and the right. While Democrats and Republicans disagree with each other (and among themselves) about how to solve those problems, they are not—for the most part—disagreeing about the list of problems to be solved.

One explanation for the gap between how bad things feel to a substantial segment of the population and how good certain economic indicators look is that many things are getting much better even as a few important things are getting much worse.

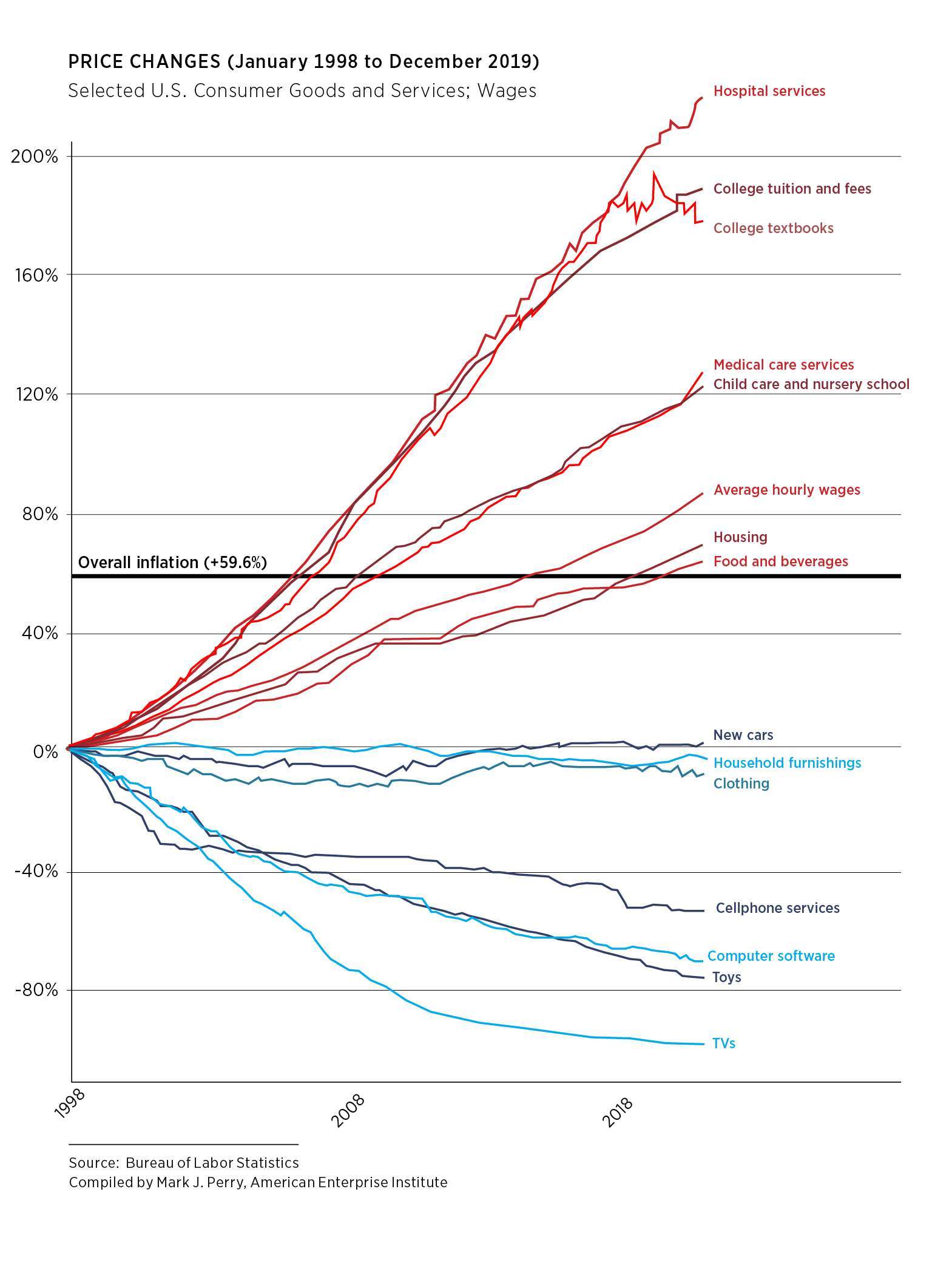

At right, you can see the sectors where things have gotten more affordable. You can also see where things have gotten more expensive—in some cases wildly more expensive. In recent decades, the incredible gains from the private sector have outpaced the costs of the burgeoning state, which is why overall economic data look pretty good. But these gains are not distributed evenly.

Some people will look at this chart and see a to-do list: Every one of the red lines, they presume, is a problem that needs to be fixed by the government. A different interpretation is that the red lines are caused by government interference. The blue lines are areas where consumers are benefitting from a relatively open global market in manufactured goods and technology.

Again, it's possible that both are true. The government has been meddling in those red-line sectors for decades, creating confused expectations about current and future prices, true levels of supply and demand, and more. Solving these problems will indeed require legislative and bureaucratic changes. But the palette of possible solutions should not be limited to sending in the feds with wagons full of money and rulebooks.

To seriously engage with the idea that the American Dream has become unaffordable, this issue of Reason delves into the question of how we got where we are today. In "Student Loans Aren't Working" (page 24), Deputy Managing Editor Mike Riggs looks at the role of federal subsidies in pushing up the price of college while destroying the ability of the market for education debt to assess risk. In "Can't Afford Your Rent? Blame Herbert Hoover" (page 32), Gallup economist Jonathan Rothwell goes back to the origins of residential zoning policy to explain a host of housing woes. And in "How Doctors Broke Health Care" (page 36), historian Christy Ford Chapin examines the way doctors, insurers, professional associations, and politicians created the United States' current confusing and cronyist medical system.

Bad things happen to politics when Americans feel like the future will be worse than the past. Reactionary and socialist ideologies ascend. The stories we tell ourselves about the problems we face have profound implications for the policy directions we take in the future. But there's much more to the story than what politicians and pundits are telling us right now.

Show Comments (139)