Yes, the Constitution Means Your Political Opponents Get Due Process Too

Americans are so locked into their political sides that many of them seem willing to cast aside some of the nation's long-established constitutional protections.

America's current political discourse is far from uplifting these days, with our increasingly tribal politics leading to a series of seemingly endless high-decibel battles. The funniest description I've read comes from a Canadian meme, which compared the situation to listening to a neighbor's car alarm blaring all night long.

The most troubling aspect of America's polarized society isn't the constant anger and upset that is so prevalent that it's making even our friendly northern neighbors a bit nervous. It's that Americans are so locked into their political sides that many of them seem willing to cast aside—or severely erode—some of the nation's long-established constitutional protections.

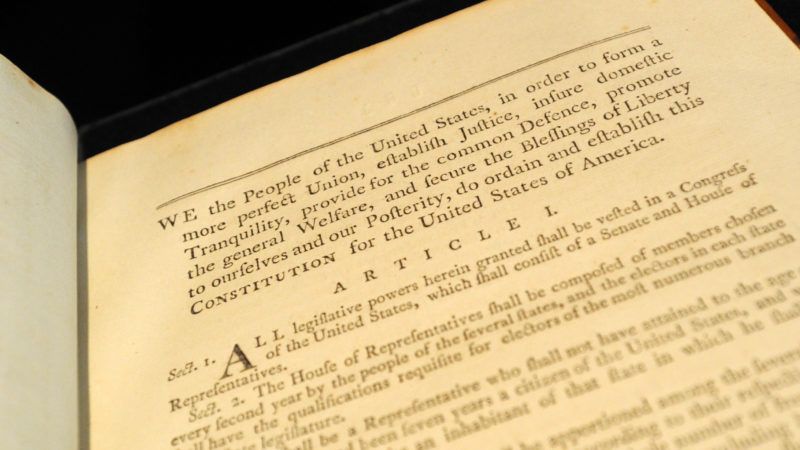

The Constitution is not a guarantor of positive rights (free health care or college tuition), but the ultimate defense of negative rights—the right to be left alone from government intrusion. Many of Facebook's newfound constitutional scholars seem to miss that basic point and employ the document selectively, mainly as a cudgel to bludgeon foes.

The latest and most disturbing hit has come against due process. The Fifth Amendment forbids the government from prosecuting crimes against individuals unless they have been indicted by a grand jury. No person shall be "deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law," nor shall their "private property be taken for public use, without just compensation."

In other words, the government cannot just arrest people and jail them without allowing them a chance to adjudicate their case before an impartial court. The government cannot simply take our private property either, except under limited circumstances and after it pays us for it. The justice system doesn't always work as promised, of course.

With property takings, for instance, the courts traditionally required that property only be taken for a public use (a government-owned road, etc.). Now, the courts allow eminent domain for "public benefit," which means almost anything that a government may claim to benefit that nebulous "public good."

Those erosions—and others like them—largely are driven by politicians who rightly see the Constitution as an impediment to their end goals. In the wake of the MeToo allegations involving sexual assault, for instance, some activists have found due-process to impose too high a burden on their desire to punish alleged miscreants.

In a recent article in the Atlantic, Megan Garber expressed frustration when film producer Harvey Weinstein's defense attorney complained about the way the system of accusations "strips your right to due process." I agree with Garber when she argues that the use of due process in a rhetorical way can be inaccurate. Due process says nothing about the court of public opinion, but only about one's right to trial before a real court.

My problem, though, is when Garber seems to take aim at the notion of due process itself: "Due process suggests the comforts of idealized thinking, summoning notions of equality and fairness and the sanctity of facts. It may be rooted in reason; in practice, though, it can look like what it has during Weinstein's trial: a perpetuation of harm."

When it comes to dealing with allegations of sexual harassment, the left has shown a troubling willingness to erode protections for the accused. Progressives were aghast, for instance, when U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos proposed new rules for colleges and universities that receive federal funds that would require that they provide more fulsome due-process protections for students accused of harassment.

The right has pushed the boundaries, too. In 2018, the president called for stripping illegal immigrants of any right to due process. He famously said after the Parkland, Fla., shooting that the government should, "Take the guns first, go through due process second." This was more talk than action, but it's troubling nonetheless.

The debate brings to mind H.L. Mencken's quotation: "The trouble with fighting for human freedom is that one spends most of one's time defending scoundrels. For it is against scoundrels that oppressive laws are first aimed, and oppression must be stopped at the beginning if it is to be stopped at all."

We're used to the usual assaults on the gun rights, of course. But those tiresome battles center on the meaning of the Constitution's words—does well-regulated militia mean I can own an AK-47?—but even gun-controllers pay lip service to the Second Amendment. I'm troubled by the prevalence of people who know say that, you know, due-process shouldn't even matter.

Some progressives want to rewrite the Constitution. "The Constitution is a political blueprint for a time when white people owned black people, the average life span was 35 years old, and news was spread through people yelling on the street," wrote one contributor on Huffington Post.

That's true, but without its protections I'm guessing America—if it were still around and democratic—would have far bigger problems than angry political debates that are keeping our Canadian neighbors awake.

This column was first published in the Orange County Register.

Show Comments (152)