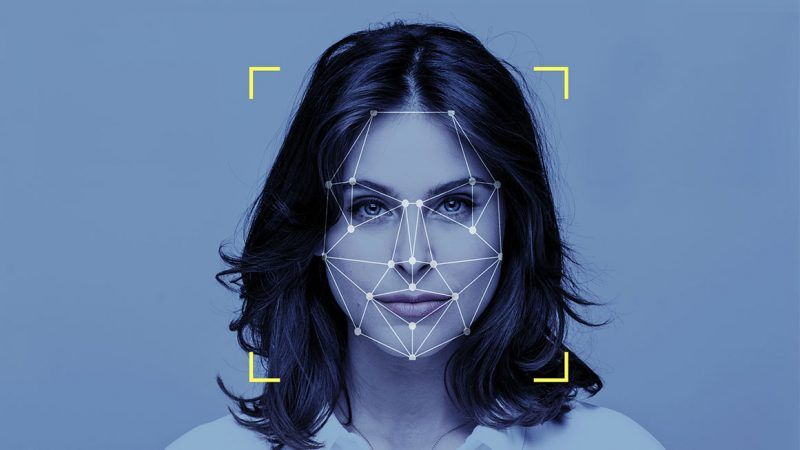

Senators Propose Limits on Police Use of Facial Recognition

Some privacy activists say the bill still falls short.

A bipartisan pair of lawmakers wants to limit the use of facial recognition technology by federal law enforcement. In November, Sens. Mike Lee (R–Utah) and Chris Coons (D–Del.) introduced the Facial Recognition Technology Warrant Act. The bill would require federal officials to seek a warrant in order to use facial recognition technology to track a specific person's public movements for more than 72 hours.

The legislation does not prohibit the use of facial recognition technology to identify people. Indeed, it allows authorities to use facial recognition to identify people without a warrant so long as "no subsequent attempt is made to track that individual's movement in real-time or through the use of historical records after the individual has been identified." In other words, the bill requires law enforcement to obtain a warrant only for long-term surveillance of a specific person.

Fred Humphries, corporate vice president of U.S. government affairs at Microsoft (which makes and sells facial recognition software), joined Coons and Lee in a joint statement in which the three claim that the bill strikes the right balance: "American citizens deserve protection from facial recognition abuse. This bill accomplishes that by requiring federal law enforcement agencies to obtain a warrant before conducting ongoing surveillance of a target."

Americans for Prosperity (AFP) also supports the legislation, which it sees as more balanced than a full ban on government use of facial recognition tools. "We're standing behind this bill," AFP senior policy analyst Billy Easley said in a statement, "because we believe in the appropriate application of facial recognition technology and ensuring it is used for good rather than the mistreatment of Americans."

Other privacy activists are less impressed. "It has gaping loopholes that authorize the use of facial recognition for all kinds of abusive purposes without proper judicial oversight," Evan Greer, deputy director of the digital rights group Fight for the Future, told CNET. "It's good to see that Congress wants to address this issue, but this bill falls utterly short." The Lee-Coons bill doesn't prohibit the feds from accessing or using the hundreds of millions of pictures they've already collected from drivers licenses and passports, for instance. In fact, it specifically approves the use of such photos.

While Congress is only just now moving to regulate facial recognition, states and cities have been grappling with the technology for at least the last year. In September, the American Civil Liberties Union helped spur a vote on legislation in California by running the official portraits of state legislators through Amazon's Rekognition program, which also contained 25,000 mugshots. As Wired reported, the program erroneously identified 25 lawmakers as arrestees.

The California Senate ended up passing a three-year moratorium on police use of facial recognition technology. Last May, San Francisco's Board of Supervisors went even further by voting to prohibit all city agencies from using any facial recognition technology.

Show Comments (36)