Trump's Trade Deal With China Is Better Than a Trade War With China. But a $200 Billion Question Remains.

Unless the tariffs are lifted, the "Phase One" trade deal might not accomplish much beyond empowering China's communist regime to tighten its grip on free markets.

President Donald Trump inked his so-called "Phase One" trade deal with China earlier this week, putting in place a framework that the White House says will boost economic growth and protect American intellectual property.

As the "Phase One" name would indicate, this isn't really an end to the trade war—in fact, nearly all the tariffs imposed by both the United States and China since hostilities commenced in July 2018 will remain in effect. Still, after 18 months of escalation and retaliation, the signing of a partial trade deal is a welcome sign that cooler heads have prevailed in Washington and Beijing.

And, indeed, the Trump administration does deserve credit for getting stronger protections for intellectual property into the deal, though it remains unclear whether those provisions can be meaningfully enforced. China has also agreed to make a series of changes to its financial services regulations that should allow competition from U.S. banks. That's potentially more important than it might appear because it reduces the odds that the world's two largest economies will fully de-couple from one another in the future.

Outside the specifics of the deal, the past year and a half may have altered the U.S.-China relationship in productive ways. "American credibility has been greatly enhanced" by the trade war, writes Tyler Cowen, an economist at George Mason University, in a column for Bloomberg. By standing up to China and demonstrating a willingness to endure the economic pain caused by the tariffs, Cowen argues, Trump has changed the calculus for how China can expect the U.S. to respond as it continues to grow. Only time will tell if that's right.

And, of course, the deal is a political win for Trump as he heads into a re-election campaign

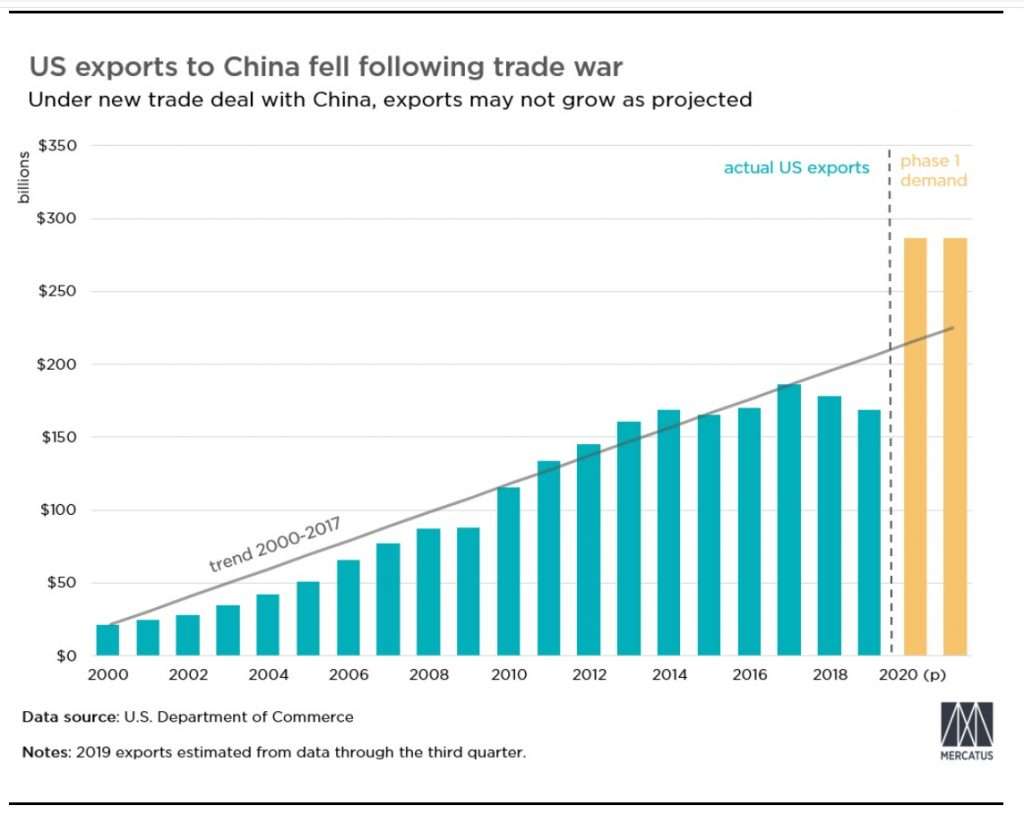

But the biggest part of the trade deal—a promise that China will boost its purchases of U.S. exports by $200 million over the next two years—should be viewed with skepticism. That part of the deal might also make pro-market reforms in China more difficult, and it reveals (once again) something about Trump's own, skewed views of international trade.

Using 2017, the last year before the trade war began, as a baseline, China has agreed to buy $77 billion in additional U.S. goods (agricultural, manufacturing, and energy exports all count towards that total) this year, and another $123 billion extra in 2021.

In 2017, total U.S. exports to China equaled about $186 billion. That means Trump is asking China to increase its purchases of U.S. goods by around 60 percent—a great leap forward that The Wall Street Journal describes as "an unprecedented jump in bilateral trade."

Even if China manages to stuff that much American corn and soy down the gullets of its people and livestock, it might be worth asking if $200 billion in exports is worth the cost.

Forcing China to buy more U.S. goods "directly contradicts the negotiating demand that China liberalize its economy and relax centralized control over trade and investment," writes Dan Griswold, a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center, a free market think tank. "With its demand that the Chinese government fulfill what are in effect quotas on purchases of U.S. goods and services, the Trump administration is only reinforcing the sway of the hardliners in Beijing at the expense of more pro-market reformers. All for a promise of more exports that may or may not ultimately materialize."

In many ways, this speaks to Trump's fundamental misunderstanding about how trade works. The president sees countries as if they were corporations: employing people to produce goods, while buying and selling with other countries. This is why he's been so fixated on the trade deficit. If you think of America as a single company, then buying more than you sell means you are losing money.

But, of course, America is not a single company, American companies are not subsidiaries of the White House's fictional national corporation, and American workers are not the president's employees.

While national government aggregate data about trade for a variety of reasons, the reality is that trade happens in an incredible diffuse way. It is the result of millions of individual decisions made by consumers and businesses every day. When "America" trades with "China," what's really happening is that some individual within America is trading with some individual inside China.

Or at least that's how it should be. It's true, of course, that China's communist government retains considerable control over markets inside the country. But requiring China to buy more American goods isn't the way to encourage more liberalization.

"This is essentially the administration saying, 'We've given up on saying we want you to become more market-oriented,'" Chad Bown, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, tells The Wall Street Journal.

It's also not clear whether China buying $200 billion of additional U.S. exports will actually add to overall American economic growth. It's possible that China could simply buy up exports that would have otherwise gone to other countries. That outcome might reduce America's trade deficit with China, but it wouldn't boost U.S. exports overall or help grow American farms or manufacturing—yet another reason why Trump's fixation on the trade deficit is counterproductive.

And as long as Trump's tariffs remain in place—there are no plans to lift them right now—they will continue to harm American manufacturing and be a drag on exports. Because tariffs raise the cost of manufacturing in the United States by taxing imported component parts, they have the added effect of making finished products more expensive, and thus less competitive on the global market. The Institute of International Finance estimates that the trade war has cost the U.S. about $40 billion in "lost exports."

China agreeing to buy more farm goods and energy from the United States won't fix those underlying issues. Unless the tariffs are lifted, Trump's "Phase One" trade deal could end up helping China's socialist regime tighten its grip on free markets while providing little to no relief for Americans.