Trump Mulls Orwellian Proposal to Stop Mass Shootings by Monitoring 'Mentally Ill People' for Signs of Imminent Violence

The program would try to develop a surveillance system based on predictive tests that don't exist.

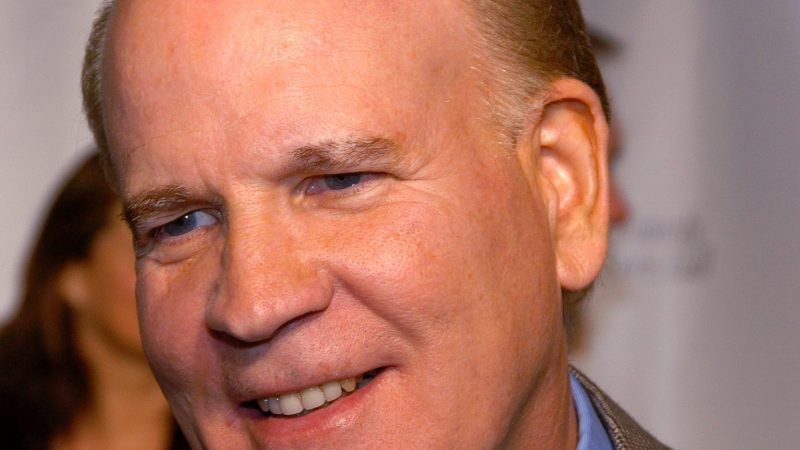

The Trump administration is reportedly considering a pitch from former NBC Chairman Robert Wright, a presidential pal, for a research program aimed at preventing mass shootings by electronically monitoring people who have received psychiatric diagnoses. That Orwellian plan may or may not be defeated by its utter impracticability.

Wright has dubbed his idea SAFEHOME—an acronym for Stopping Aberrant Fatal Events by Helping Overcome Mental Extremes. The Washington Post reports that his three-page proposal imagines using "technology like phones and smart watches" to "detect when mentally ill people are about to turn violent." The idea, the paper says, is to look for "small changes that might foretell violence."

The Post notes that "only a quarter or less" of mass shooters "have diagnosed mental illness." But that is only the beginning of the difficulties with this half-baked scheme.

The larger problem is that the percentage of "mentally ill people" (a group that, by some estimates, includes more than a quarter of the U.S. population in any given year) who will use a gun to commit mass murder is approximately zero. Likewise for the general population, since mass shootings are very rare events, accounting for less than 1 percent of gun homicides.

A 2012 study that the Defense Department commissioned after the 2009 mass shooting at Fort Hood in Texas explains the significance of that fact in an appendix titled "Prediction: Why It Won't Work." The appendix observes that "low-base-rate events with high consequence pose a management challenge." In the case of "targeted violence," for example, "there may be pre-existing behavior markers that are specifiable." But "while such markers may be sensitive, they are of low specificity and thus carry the baggage of an unavoidable false alarm rate, which limits feasibility of prediction-intervention strategies." In other words, even if certain "red flags" are common among mass shooters, almost none of the people who display those signs are bent on murderous violence.

The Defense Department report illustrates the problem with a hypothetical example. "Suppose we actually had a behavioral or biological screening test to identify those who are capable of targeted violent behavior with moderately high accuracy," the report says. If "a population of 10,000 military personnel…includes ten individuals with extreme violent tendencies, capable of executing an event such as that which occurred at Ft. Hood," a test that correctly identified eight of those 10 dangerous people would wrongly implicate "1,598 personnel who do not have these violent tendencies."

That scenario assumes a predictive test that does not actually exist. "We cannot overemphasize that there is no scientific basis for a screening instrument to test for future targeted violent behavior that is anywhere close to being as accurate as the hypothetical example above," the report says.

The research program imagined by Wright is aimed at developing a predictive test. But even in the unlikely event that it succeeded, the enormous false-positive problem would remain.

"According to a copy of the SAFEHOME proposal," the Post says, "all subjects involved [in the research] would be volunteers," and "great care would be taken to 'protect each individual's privacy,'" while "'profiling of any kind must be avoided.'" It is hard to see how profiling can be avoided, since the whole premise of the project is that people who fit a certain psychiatric profile are especially prone to mass murder.

Once the research has been completed, of course, the resulting information would be pretty useless if it could be deployed only against volunteers. So how would that work? Would people with certain psychiatric diagnoses be legally required to carry electronic monitors aimed at detecting "small changes that might foretell violence"? How could such a requirement be reconciled with due process or the Fourth Amendment?

Maybe the requirement would be limited to people who pose an especially high risk of violence. But how would they be identified? Since mental health specialists are notoriously bad at predicting violence, SAFEHOME would have to develop two kinds of tests: one that identifies people who are prone to violence and one that predicts when those people are about to commit a crime. "I would love if some new technology suddenly came along that would help us identify violent risk," Marisa Randazzo, former chief research psychologist for the U.S. Secret Service, told the Post, "but there's so many things about this idea of predicting violence that [don't] make sense."

The Post also interviewed Johns Hopkins neurologist Geoffrey Ling, who advised Wright on his proposal. "To those who say this is a half-baked idea, I would say, 'What's your idea? What are you doing about this?'" Ling said. "The [worst] you can do is fail, and failing is where we are already." Given the potential for mass stigma, invasions of privacy, and violations of due process, I'd say we can do a lot worse than failing.

Show Comments (84)