How Innovative Responses to Prohibition Set Off a Deadly Fentanyl Explosion

A RAND report highlights the importance of new synthesis methods, cheap international shipping, and online distribution aided by privacy-protecting technologies.

In 2017, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, "synthetic opioids other than methadone," the category that includes fentanyl and its analogs, were involved in nearly 29,000 opioid-related deaths, or 60 percent of the total. The actual numbers are probably higher, because many of the coroners and medical examiners who share death records with the CDC do not test for fentanyl or related substances.

As Bryce Pardo and five other drug policy researchers note in a new report from the RAND Corporation, this situation is historically unprecedented. Back in 1975, the psychonautical chemist Alexander Shulgin predicted that synthetic opioids like fentanyl, which was first formulated in 1960, would be introduced in the black market as substitutes for heroin, which is derived from poppies. "The term 'when' rather than 'if' heroin substitutes appear is used intentionally, for this transformation seems economically inevitable," he wrote. Yet while fentanyl has been implicated in several overdose clusters since the 1980s, it did not emerge as a major factor in drug-related deaths until 2014 or so.

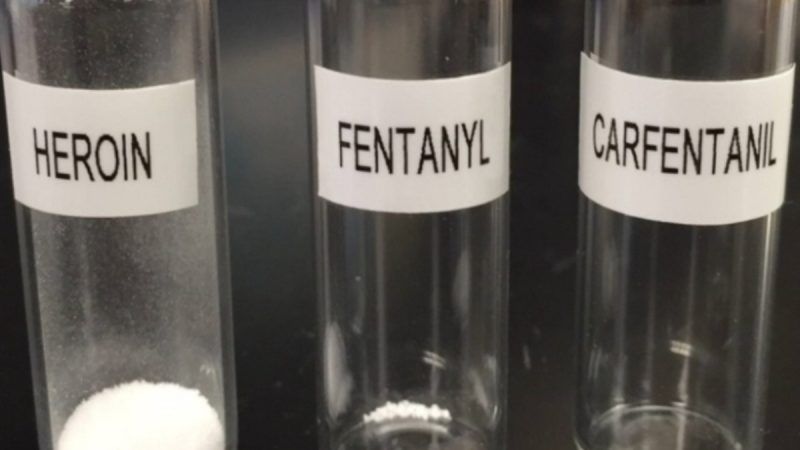

Fentanyl is roughly 50 times as potent as heroin, so its proliferation as a heroin additive and replacement has increased the variability of black-market opioids, making fatal outcomes more likely. Since 2013, the annual number of deaths involving synthetic opioids has risen ninefold, while the total number of opioid-related deaths has nearly doubled. The number of people using illicit opioids has not increased commensurately; rather, fentanyl and its analogs (some of which are even more potent) have made "heroin" use deadlier.

"Why now?" Pardo and his co-authors ask. Their answer highlights changes in drug production and distribution that created the conditions for the fentanyl explosion: innovations in synthesis that have made the process less complicated; a sprawling, weakly regulated Chinese chemical industry that supplies most of the fentanyl consumed in the U.S.; cheap, high-volume international shipping that makes fentanyl easy to send and hard to detect; and online outlets that take advantage of privacy-shielding technologies such as TOR and Bitcoin to supply fentanyl directly to U.S. distributors and consumers. But none of these developments would have created the current situation without the economic incentives created by prohibition.

Those incentives, as Shulgin suggested, are powerful. Fentanyl is favored by the same factors that favored distilled spirits over beer and wine during alcohol prohibition and heroin over opium after nonmedical use of opiates was banned. Dose for dose, fentanyl is much less bulky than heroin and therefore much easier to smuggle. And unlike heroin, it does not require poppy crops and extensive processing of a raw agricultural product, so it is much cheaper for producers and distributors.

How much cheaper? RAND researchers found that Chinese firms will ship a kilogram of nearly pure fentanyl for $2,000 to $5,000, compared to around $25,000 for a kilogram of imported heroin. But that comparison does not take into account the higher potency of fentanyl or the greater dilution of heroin. Expressing prices in terms of morphine equivalent doses (MED), Pardo et al. calculate that "a 95-percent pure kg of fentanyl at $5,000 would generally equate to less than $100 per MED kg," while "a 50-percent pure kg of Mexican heroin that costs $25,000 when exported to the United States would equate to at least $10,000 per MED kg." In other words, "heroin appears to be at least 100 times more expensive than fentanyl in terms of MED at the import level."

Pardo et al. emphasize that, by and large, opioid users are not clamoring for fentanyl, which makes their habits more dangerous by making potency harder to predict. Replacing heroin with fentanyl is instead a logical choice for suppliers dealing with government efforts to suppress the drug trade, since it makes drug production and distribution less conspicuous and more profitable.

At the same time, the shift toward fentanyl opens up the market to people who otherwise might never have contemplated a career in drug dealing. "The ability of enterprising drug dealers to obtain fentanyl and other related substances without leaving the comfort of their homes reduces barriers to market entry," Pardo et al. write. "Importantly, this obviates the need to interact with violent criminal organizations that smuggle drugs across international borders. Access via the internet and mail link[s] manufacturers and buyers even when they are thousands of miles apart, diminishing the risks and costs associated with smuggling the drug."

For related reasons, the rise of fentanyl may also reduce the violence associated with drug trafficking. "If synthetic opioids drive heroin out of most markets, it could erode the power of the DTOs [drug trafficking organizations] that dominate Mexico's poppy-growing areas and cut their revenues from cross-border smuggling operations," Pardo et al. write. "In the short run, this might generate more violence as the DTOs compete for a declining market, but in the long run, it could reduce violence and corruption in Mexico…..Online distribution could reduce opportunities for in-person transactions that might result in violence and obviate the need for armed and potentially violent criminals to smuggle product across borders." They add that if the cost advantages of fentanyl translate into lower retail prices, the upshot could be less theft committed by heavy users.

Those potential silver linings should not obscure the dark cloud of uncertainty that hangs over drug users because of prohibition, forcing them to deal with mystery powders and tablets of unknown provenance and composition. This fundamental hazard of the black market has only been magnified by the emergence of fentanyl.

Still, the dark web marketplaces that make it hard to disrupt the fentanyl trade can provide a partial solution to that problem. Some drug sites have banned fentanyl sales, giving consumers some assurance that the products they buy will not turn out to be more potent than expected. More generally, because sites and vendors have a stake in maintaining the reputations that bring them repeat business, consumers have more control over quality than they do when buying from random street dealers.

Pardo et al. offer a few suggestions for disrupting online vendors, improving detection of fentanyl in the mail, and pre-emptively suppressing fentanyl sales in parts of the country (states west of the Mississippi, for example) where they are not yet common. But in general, they are appropriately skeptical of standard supply-side responses to fentanyl-related deaths. "There is little reason to believe that tougher sentences, including drug-induced homicide laws for low-level retailers and easily replaced functionaries (e.g., couriers), will make a positive difference," they say. "There is also little reason to believe that synthetic opioid production, which occurs mostly in China, could be curtailed in the short run."

The report suggests several harm-reduction policies that have greater promise, including expanded "medication-assisted treatment" (MAT) with methadone and buprenorphine. More boldly, Pardo et al. say it might make sense to relax current restrictions on MAT, expand the opioid replacement options to include pharmaceutical heroin or hydromorphone, and legalize supervised drug consumption sites. They also suggest research aimed at providing consumers with drug-testing kits that can indicate the concentration as well as the presence of fentanyl. Although "we are not endorsing these options," they say, "it might be time to invent new approaches and be open to trying ideas that seemed too risky or too alien in the past."

Show Comments (13)