Quentin Tarantino's Once Upon a Time in Hollywood Is a Nostalgic Defense of Movie Violence

It's a throwback to an earlier Hollywood era, and an argument for why movies still matter.

It wasn't too long ago that just about every young filmmaker wanted to be Quentin Tarantino. His 1992 debut, Reservoir Dogs, roiled the Cannes film festival before becoming a cult favorite, and his follow-up, Pulp Fiction, became the first independent film ever to gross $200 million at the box office. Tarantino's cinema-steeped films were vulgar, violent, quirky, and cool, and they quickly became part of the nation's cultural lexicon, both widely celebrated and widely criticized. People may not have seen Tarantino's movies, but they knew his name and knew (or thought they knew) what he stood for, or at least knew the vibe. His early films remain signifiers of the Clinton era, as much as Nirvana and MTV News.

Now in his 50s, the one-time enfant terrible has become a Hollywood grand eminence, a singular voice rather than a generational influence. He makes a new film every few years or so, and for the most part they remain pretty good. Indeed, his latest, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, is his best in years, and it acts as a kind of summation of his career; of his particular interests, from the role of stories to kung-fu movies to women's feet; even of the arc of Hollywood itself.

But Tarantino isn't playing the role he used to play. He used to be a guy who everyone wanted to be. Now he's just a (very successful) guy.

In some ways this is a relief. The wave of Tarantino wannabes who popped up to make Tarantinoesque movies—profane, pop-culture-obsessed crime pics—rarely understood what made his best films so exceptional, the clever way he fused talky naturalism with genre tropes, creating a cinematic world in which almost normal people found themselves thrown into movie-ish situations as a way of capturing and collapsing the gap between the world on screen and the real, actual world we actually live in. Tarantino's imitators got that he was violent and hip, that his characters spent a lot of time engaged in geeky, banal chit-chat. But in most cases, they didn't understand why. They were making movies about Quentin Tarantino movies; Tarantino was making movies about the very idea of movies—how they work, what they mean, and their place in our lives.

Yet in another way, it's a little bit of a disappointment to see his influence wane. Not because we need more Tarantinoesque films (we don't), but because we could probably use a few more filmmakers who set out to do what Tarantino did: Make films that reflect their own sensibilities and interests, that feel as distinct as faces. For better or for worse, you can see Quentin Tarantino in every frame of every one of his movies.

It's not that no one makes oddball indie films anymore, but today's most successful filmmakers seem increasingly willing to move on to making studio franchise entries that bare only the slightest hint of their personalities. Disney in particular has a habit of picking up successful small-scale directors and putting them at the helm of megamovies. Marvel's expanded cinematic universe, an arm of Disney, is notable for the reasonably consistent quality of its films, but also for the way it has enforced stylistic conformity. Even the most distinctive of Marvel's movies—James Gunn's Guardians of the Galaxy, Ryan Coogler's Black Panther—feel more like Marvel films than like products of their director's unique voices. These are still bylined pictures, but they play like work for hire.

By contrast, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is the sort of film that no other director could have made. Tarantino has always dwelled on a handful of subjects—the City of Los Angeles, the nature of violence both on screen and off, improbable redemptions and elaborate fantasies of deferred revenge—and this is a movie about all of them.

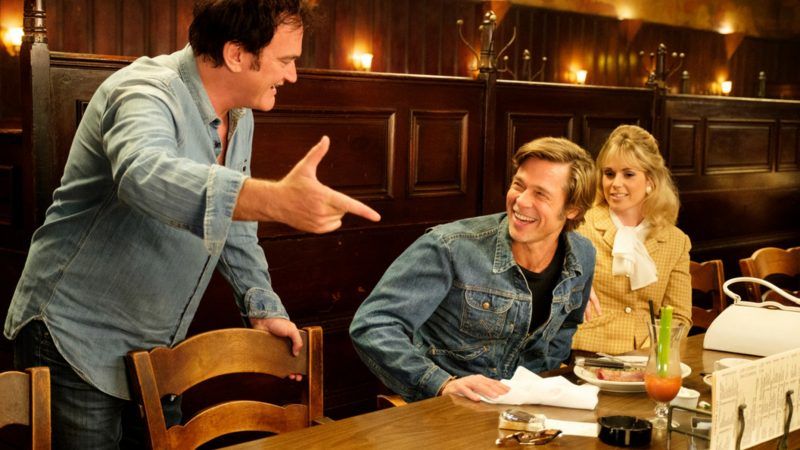

Set in late 1960s L.A. just before the Manson Family murdered actress Sharon Tate (played with wide-eyed perfection by Margot Robbie) and several others, the film is the story of Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio), an aging leading man who happens to live next to Tate's home in Hollywood Hills, and Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt), his stunt double, house servant, and ever-present drinking buddy.

It's a laconic, gorgeous, and gently nostalgic look at old Hollywood, at its frivolity and ridiculousness and obsession with the low pleasures of cheap violence, and the ups and eventual downs of big-screen fame, which Tarantino surely knows something about. But it is also a defense of movies, and in particular of movie violence. Like several of Tarantino's previous films, Hollywood delivers catharsis in the form of exquisite cinematic revenge, with the movie itself serving as the vehicle for an operatically violent righting of real-world wrongs.

This is familiar territory for Tarantino, who has long been criticized for being too violent, too sick, a cancer on the culture. In 1995, when then–Senate majority leader and GOP presidential hopeful Bob Dole complained about two movies that Tarantino had scripted, Natural Born Killers and True Romance, an irritated Tarantino shot back: "This is the oldest argument there is. Whenever there's a problem in society, blame the playwrights: 'it's their fault, it's the theater that's doing it all." Dole, Tarantino complained, hadn't even seen the movies he was complaining about.

It's not too much of a stretch to see Hollywood as an elaborate continuation of that idea. Although it is set in a reverential recreation of late 1960s Los Angeles, its true nostalgia is for the 1990s movie scene in which Tarantino made his name. It deals not only with the role of violence in film, a question that occupied far more of our national conversation in the years before Twitter, but with the coming of a new generation of movie stars and new ways of making movies—the markers of generational change that Hollywood is dealing with yet again.

Tarantino has made a movie about a fictional movie star coping with becoming a has-been; it's hard not to see echoes of his own arc as a filmmaker whose cultural capital, while still significant, has declined.

Yet the lavishly produced, star-studded Hollywood is also a case for his continuing relevance as a top-tier filmmaker, and, more grandly, for the relevance of movies as a means of inducing both pleasure and cultural conversation. It's a defense of the idea that filmmakers all have something worthwhile to say, even and perhaps especially when they depict violence. Which is to say, it's a distinctive argument made by a distinctive filmmaker, the product of years of making—and thinking carefully about—movies and their place in our lives. We may not need more Quentin Tarantinos in Hollywood, but we sure could use more of that.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Suderman on film: zzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz

Seriously, I'd rather read Pete on his favorite mixed drinks. Please, Pete, stick to health care and the utter moral and spiritual decay of the Republican Party, topics that are actually worth writing about.

Did you see this before Kadın Giyim

Good review. One can analyze something to death, however. But, you can take it from me. My wife and I saw this last night. Overall, I think it is Tarantinos' best work.

Great movie.

Is that miserable one-trick hack from the '90s still making movies?

It's a pretty good trick though.

Alright, okay. Jackie Brown is one of my favorite movies ever. I'm a contrary sunuvabitch sometimes.

I had to walk out halfway through Reservoir Dogs, and didn't see his next movie because of it. Violence for the sake of violence is not art. If I wanted that I could go watch a Rob Zombie film and cut out all the artsy crap. Tarantino was too obsessed with the form to understand that he needed function as well.

Reservoir Dogs is about way more than "violence for the sake of violence" as are all of his films. However I get that it can be a bit much for some people (my wife included).

If you're not familiar with his other stuff Jackie Brown is a great film without much violence, and Pulp Fiction (IMO one of the best movies ever made) has some disturbing scenes but not to the level of, say, Reservoir Dogs or Kill Bill.

Jackie Brown is a great film yes. Everyone should see it.

Was. Not is.

>>>Make films that reflect their own sensibilities and interests, that feel as distinct as faces.

people are less distinct now.

"Tarantino has made a movie about a fictional movie star coping with becoming a has-been; it's hard not to see echoes of his own arc as a filmmaker whose cultural capital, while still significant, has declined"

I haven't seen the film yet, but it seems to me that the whole idea of telling new stories has declined. Don't pin it all on Tarantino. They hardly make big budget films for adults that aren't based on a preexisting property anymore.

If it's an original story with big name actors who are doing something that didn't already exist as a comic, a book, or is a movie for kids . . . that's not a Tarantino movie. That's the way they used to everything. After the studio system collapsed, they started doing movies like that--and that was the state of film industry from the end of the 1960s until at least the end of the 90s.

In that era, it used to be that you could get a budget to do pretty much anything you wanted so long as you had a bankable star. That isn't enough anymore. You need a bankable property. Few people get $100 million to do whatever they want. It needs to have a built in audience.

If you took an English composition class at UCLA in the 1990s, they'd tell you that you shouldn't bother writing books. The medium was film, and we were in Los Angeles. If you can write, write for film. You don't want to be the next Thomas Pynchon or Phillip Roth. You want to be the next Coen Brothers or David Lynch. I'm not sure there's a market anywhere for literary people anymore.

There's a market for lit, but it's a buyer's market, and the modal, median, and damn near mean price is 0, thanks to the 'nets.

It’s a sellers market Vince. Now white people who know? This is the house they come to, I’ll take the Pepsi challenge on that Amsterdam shit any old fucking day of the week.

"I haven’t seen the film yet, but it seems to me that the whole idea of telling new stories has declined. "

In the multiplex, yes. On the small screen, no. That's the place to go now for original, new non-comic book entertainment.

I was going to say QT is the only one still doing original content in movies. But I honestly don't know.

Shane Black and Michael Mann are also very good film makers who are in love with LA. See their, respectively, The Nice Guys and Collateral. See also Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang and Heat.

Back in the summer of 1999 we had pulp fiction playing in the background all day all night, only getting drowned out by sublime when the beer showed up. Best days of my life.

I can take or leave most of Tarantino's movies, but he seems to get some great performances out of actors and does write compelling dialogue. I might check out this film when it comes to VHS.

It is a terrible movie. Certainly no Django. Slow, boring and a very bad premise to boot. Too much hype....Lion King was King

I love how Reason is so de-centralized that Loder and Suderman can publish vastly different takes on the same movie for the same publication on the same day. If Reason ever wrote a tribute to Hayek it would be done by WhatsApp or Slack Group chat one phrase at a time by 8 different editors /writers