If Cops Don't Die From Incidental Fentanyl Exposure, a Drug Treatment Specialist Warns, They 'Could Become Addicted to It Instantly'

Such scaremongering poses a potentially deadly threat.

When Iraq fired Scud missiles at Israel during the Persian Gulf War in 1991, many people near the first blast reported breathing problems, which made sense in light of fears that the missiles carried chemical or biological weapons. But it turned out that the missiles had no such payloads, meaning that the symptoms were a product of anxious anticipation rather than physical causes. Something similar seems to be happening in the United States among police officers who encounter people who have overdosed on illicit fentanyl.

The latest example is an incident in Hazleton, Pennsylvania, early last Friday morning, when three officers responded to a call about a man who had overdosed. WBRE, the NBC station in Wilkes-Barre, reports that "all three became ill and it could have been much worse." After the officers "were exposed to the highly addictive and potentially deadly opioid fentanyl," WBRE says, "one officer nearly overdosed," while the other two felt unwell. Hazleton Police Chief Jerry Speziale explains the context:

My officer goes to pull him out, the first officer on scene. They hit him with Narcan [a.k.a. naloxone, an opioid antagonist], and when he does he realizes that on the individual's chest and on his face and around his nose is fentanyl. The other two officers were a little bit sketchy. They checked their vitals. He started to feel a little weird right away, so when EMS got to the scene they checked him out. His vitals were a little off. They transported him immediately. They called me in the middle of the night. I said get him to the hospital right now. They Narcanned our officer.

Given how difficult it is to absorb fentanyl through the skin (which is why the companies that make legal fentanyl patches for pain treatment rely on patented technology that took years to develop), the likelihood that these officers were actually feeling the narcotic's effects is approximately zero. Fortunately, WBRE consulted a drug treatment specialist…who proceeded to confirm all the worst fears about incidental exposure to fentanyl and upped the ante by claiming that first responders who don't die can end up accidentally addicted to the drug:

Jason Harlen has worked in addiction counseling for 20 years. He says the officers were very lucky. It could have been a much different outcome.

"Fentanyl is extremely addictive. Someone, say a first responder or a family member, who enters a room with a person who's having an issue with fentanyl could become addicted to it instantly [emphasis added]. It's that strong of a synthetic drug made by humans," Harlen said.

As the journalist Maia Szalavitz pointed out on Twitter, there is no such thing as instant addiction. Addiction is a gradual process through which people become strongly attached to an experience that provides pleasure or emotional relief. Individual characteristics and circumstances play a crucial role in that process, which is why patients who take prescribed opioids, including fentanyl, for pain relief rarely become addicted to them. So even if these officers somehow absorbed enough fentanyl to experience its psychoactive effects (say, by accidentally injecting themselves with a loaded syringe found at the scene), they would not become addicted to it unless they liked those effects enough to repeatedly seek them out, which they clearly did not.

Wilkes-Barre is my hometown, and my first job out of college, as a police/general assignment reporter on the night shift at The Times Leader, required me to simultaneously watch the evening newscasts on WBRE and the other local stations, in case they had any scoops that I needed to follow up on. That experience helps explain my lifelong hatred of local TV news, which tends to credulously pass on whatever law enforcement agencies say, especially when the story is scary and the subject is drugs (which is not to say that the national networks are immune to such scaremongering.) When TV stations bother to interview additional sources, it is usually to amplify police claims and rarely to question them. In this case, the "expert" consulted by WBRE clearly has no idea what he is talking about.

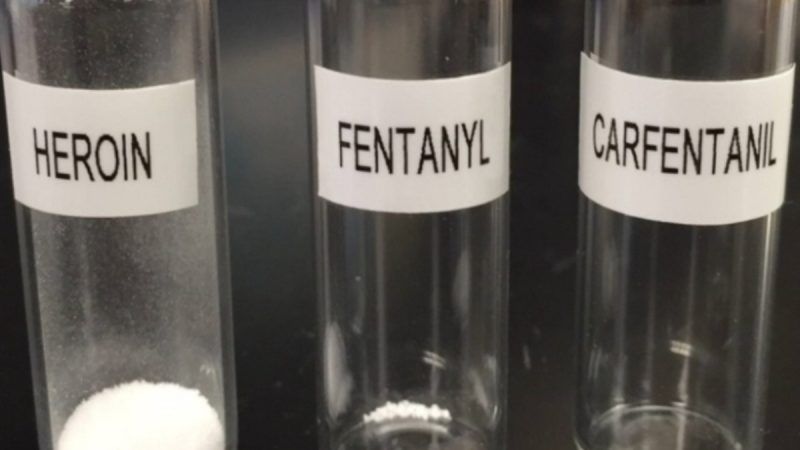

In a 2017 Slate article headlined "The Viral Story About the Cop Who Overdosed by Touching Fentanyl Is Nonsense," Jeremy Faust, a Boston E.R. physician and clinical instructor at Harvard Medical School, noted that "neither fentanyl nor even its uber-potent cousin carfentanil (two of the most powerful opioids known to humanity) can cause clinically significant effects, let alone near-death experiences, from mere skin exposure." Faust quoted Harvard medical toxicologist Ed Boyer, who flatly stated that "fentanyl, applied dry to the skin, will not be absorbed."

A few months later, my colleague Mike Riggs interviewed Stanford anesthesiologist Steven Shafer, who said "fentanyl is not dangerous to touch," adding that "transdermal fentanyl patches deliver fentanyl across the skin, but they require special absorption enhancers because the skin is an excellent barrier to fentanyl (and all other opioids)." Shafer did note that fentanyl "is readily absorbed through mucus membranes, so snorted, rubbed in the mouth, or swallowed are all effective ways of administering fentanyl." Neither the incident in Hazleton nor the other cases where first responders reportedly had brushes with death by fentanyl overdose seem to have involved such administration.

As Walter Olson noted here last June, the implausibility of these accidental overdose stories has not stopped members of Congress from rushing to address "a fentanyl problem that fentanyl experts say probably does not exist." The danger of lending credence to these reports should be clear: If first responders perceive drug users as potentially deadly threats, requiring officers to conduct field testing, don gloves, and take other precautions (hazmat suits?) for their own protection before rendering aid, people who have overdosed are less likely to promptly get the help they need to survive. The deadly threat here is not fentanyl users but fentanyl phobia.

Show Comments (43)