How Vietnam Gave Us C-SPAN

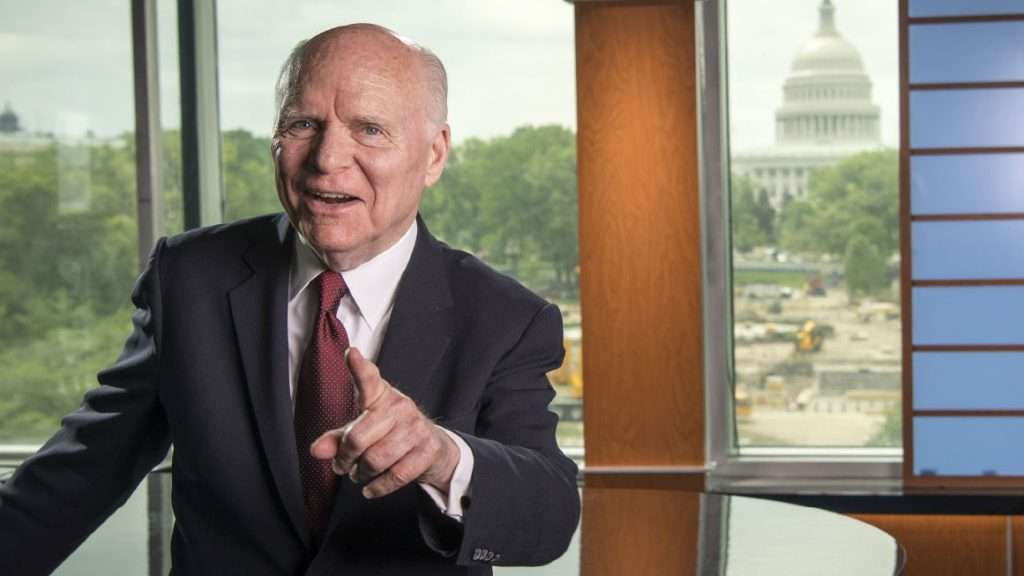

Brian Lamb, the network's founder, is stepping down as CEO after 40 years of putting cameras on Congress, hosting in-depth interviews, and creating an enduring home for diverse civil discourse.

On May 19, 2019, a major era in American media and politics quietly ended. Brian Lamb made his final official weekly* appearance on C-SPAN, the public affairs television network he launched 40 years ago. Fittingly, that last show was an in-depth interview with historian David McCullough, whose work often chronicles how previously underappreciated figures such as Harry Truman and John Adams radically transformed American history.

The 77-year-old Lamb could be one of McCullough's protagonists. He didn't just anticipate our era of transparency, in which governments, corporations, and other institutions are held accountable to an extent once unimaginable; he helped to create that era by effectively turning surveillance cameras on Congress. In 1979, C-SPAN started broadcasting live coverage of the United States House of Representatives. Long before reality TV shows such as Real World, Survivor, the Real Housewives franchise, and Sober House entered the zeitgeist, C-SPAN gave Americans direct, unmediated access to one of the most powerful groups of people on the planet. For the first time in history, we could see our elected representatives arguing, wheeling and dealing, and literally falling asleep during debates over federal budgets, foreign policy, tax plans, and much more.

In 1986, C-SPAN started covering the Senate in a similar fashion, giving us unadulterated views of confirmation hearings of Supreme Court justices, cabinet secretaries, and other high-level appointees. Other programming—ranging from live, comprehensive coverage of the Iowa caucuses to bus tours of presidential libraries and other off-the-beaten-track locales to hourslong interviews with authors, policy makers, and politicians—soon followed.

C-SPAN famously doesn't pay attention to ratings, because Lamb has long suspected that data on audience size would subconsciously redirect attention from what he considered important topics to merely popular ones. But in any given week, cable ratings show, about 20 percent of households tune in to the network. An early adopter when it comes to technology and distribution, C-SPAN has a remarkably robust, user-friendly, and free website that allows visitors to search through video clips and transcripts of 240,000 hours of archives. Clarence Thomas' confirmation hearings are there, along with Joe Biden's withdrawal from the 1988 presidential race, Rand Paul's epic 13-hour anti-surveillance filibuster from 2013, and dozens of appearances by Reason staff over the years.

If the typical cable news impresario is brash, arrogant, overbearing, and incapable of thinking in chunks of time longer than a few minutes, Lamb is the opposite. He speaks quietly and self-effacingly, and he prefers expansive, substantive programming to the partisan rat-a-tat-tat that defines contemporary cable news.

Born in 1941, Lamb joined the Navy in the early 1960s and was assigned to do media relations for the Pentagon during the Vietnam War. That experience, and a frustration with the superficial nature of broadcast coverage of important political matters, ultimately gave birth to the idea for C-SPAN.

Lamb also worked at the Office of Telecommunications Policy, a federal agency that was instrumental in deregulating the satellite industry in the 1970s. Under the "Open Skies" policy, the number of domestic communications satellites increased dramatically and quickly, thus making it possible for cable systems to provide original programming on a cheap, coast-to-coast basis by pulling signals from those satellites. The rise of cable TV in the 1970s, Lamb explains, provided a way to work around ABC, CBS, and NBC. "The most important thing to me was reducing the power of the three networks so that we had more opportunities to see more sides of more issues," he says. In the late 1970s, he pitched a group of cable executives on a network that would provide long-form coverage of politics and culture. American media would never be the same.

In March, as C-SPAN was celebrating its 40th anniversary, Lamb spoke with Reason's Nick Gillespie via phone about his four decades of fostering civil discourse and transparency. Later that month, he announced he would be stepping down as CEO.*

Reason: Set the scene for me. Why did you want to create C-SPAN? What need did it serve?

Lamb: I grew up in the very nice little town of Lafayette, Indiana, and I joined the Navy and went off to see the world. As I started to see the world, I realized how much was available in certain parts of the country that wasn't available to me in Lafayette. I grew up watching the three big networks that were located in New York City. I started doing radio and television when I was in high school and college. I went to Purdue, and it seemed to me that we were getting the same message from everybody. The three networks had an enormous amount of power. I didn't find anything bad about them—it's just they had so much power, and there was so much more going on in the world [that they weren't showing us].

During the Vietnam War, you worked for Defense Secretary Robert McNamara and President Lyndon Johnson. You also worked in Richard Nixon's White House. How did this affect your desire for government transparency?

Well, it's a stretch to say that I worked for Robert McNamara. I was in the Pentagon, working in the Defense Office of Public Affairs. My immediate boss was a lieutenant colonel in the Air Force. I didn't get close to Robert McNamara. At the same time, I was also a social aide for Lyndon Johnson, and I would be invited to come to the White House and work their social occasions. You really just did what the social secretary told you to do. I spent two years doing that in the middle of the Vietnam War.

I had worked on the 1968 Nixon campaign, and I hate to keep saying this, but it's important just to understand how close I wasn't. I wanted to go to work in the Nixon White House communications office, and I didn't get the job. Eventually I went up to Capitol Hill in a little office called the Office of Telecommunications Policy [which pushed for deregulation of satellites]. Frankly, I had tried to go to work for ABC, NBC, and CBS, and they all said no. Eventually, the good news was that power was taken away from NBC, ABC, and CBS by the creation of the [cable industry]. That's how I got involved.

Were those experiences spent on the periphery of power important to developing a sense that we should be seeing how government works?

Extremely important, but the most important thing to me was reducing the power of the three networks so that we had more opportunities to see more sides of more issues. People in the cable [industry] were willing to take a chance with us because they knew that we were going to be televising the House of Representatives. They understood what that meant. And also it was going to be done in a very inexpensive way.

When cable started, it was a bunch of men—almost all men—who got into the business of cable television to serve communities that didn't have clear pictures [from broadcast]. They were in mountainous regions and small towns, and they would deliver the channels from the big cities so that [viewers would] have some choice. It started out just that basic, because it was too expensive to be able to transmit programs all over the United States.

Then the satellites came in around 1974–75 [creating the ability of cable providers to transmit original, affordable programming all over the country]. HBO was the leader, showing movies without ads all over the United States on these cable systems. Everybody started seeing the opportunity, because you could bring in something unique. It didn't have to be just another over-the-air television station. And so all these guys that were in that business were looking for new ideas [for cable channels], and I just came into the middle of that and said, "I have an idea."

An ad hoc group of cable television system owners had these meetings, and they would invite people to come in and pitch them. I was just one of those guys that got 30 minutes one day out of the goodness of the fellow's heart that ran the thing. My pitch was: Let's do something other than movies and sports. Let's do public affairs television, and let's start in a limited way.

A fellow who liked the idea went back to the industry, and they said, "No, we don't want to pay for that." Then it was a month or two later that the idea popped up to [put a camera in] the House of Representatives, and that's when they said, "Yeah, we like that one. We will pay for that one."

I made it really clear to them that I had absolutely no interest in putting it together in a way that would require taxpayer money. This should be independent of all government connection, and it would be a journalistic institution, and we wouldn't be regulated, and we could make up our own minds.

What are some of your favorite moments over the past 40 years?

I think the most significant thing was the change of leadership [in the House of Representatives]. Watching that process, from 1979 when Tip O'Neill was in charge to 1995 [when Newt Gingrich took over], was the most important thing that we've been able to see. The Republican Party had been out of power for 40 years.

I must say: I thought that when the American people could see how the money was spent that they would be more responsible, and it's just been the opposite.

Is that an unintended consequence of filming lawmakers? People were like, "Now that I see that everybody else is getting money, I want mine too. Just put it on the credit card."

I don't know. I've never thought about the unintended consequences. We used to get a lot of criticism because people would say that the presence of cameras changed [the way politicians govern]. But the number of hours that they're in session has not changed. You do see more people show up at some of these hearings—members of Congress [actually attend] instead of having just their staff sit there and tell them what happened. I think one thing is that now a lot of people around the country know what their [representatives and senators] look like.

When I first came to town, Margaret Chase Smith was the only woman in the Senate. There are now 23 women. And there are all these new members of Congress who are attractive and well-spoken and interesting and have good backgrounds, and we've covered them all.

C-SPAN has always been an early adopter of technological innovation. You were early streamers of content online. You supply transcripts of everything. You let people make and circulate their own clips. Where did that vision come from?

It's all part of a group of people here who came when they were 22 and now they're 55, and they were able to build this place out of whole cloth. Every time you see things change, you say, "We've got to be a part of it." We were the first ones to stream nationally on the internet in 1995, free of charge to everybody. Nobody paid a whole lot of attention to it at the time, but now [live streaming is] the flavor of the day.

Your archives are this incredible repository of meaningful conversations that are waiting to be mined for insight and history.

Robert Browning, a professor at Purdue University working with us, created the archive. We now have 240,000 hours of [material] that anybody can see and use worldwide, free of charge. You don't have to pay a dime to anybody. This is all a product of what cable television executives decided to do back in the late '70s.

You have a lot of programming besides the House and the Senate. There's Washington Journal, a call-in show with journalists, politicians, and activists; all the Book TV programs, where you do in-depth interviews with writers; coverage of events all over the country. How do you come up with those types of programs?

We started our first call-in show on October 7, 1980. I said this was an opportunity for the public to talk back to the television set. I had listened to Larry King, who started his nationwide radio call-in show in 1978. We came along and said, "Let's do [call-ins] all the time." There's nothing magic about this place other than we were really given an opportunity by our board of directors to experiment. They never looked over our shoulder and said, "Do this; don't do that."

I remember the exact [inspiration for our book coverage]. I was really anxious to see Neil Sheehan's book, A Bright, Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam. I grew up in the Vietnam War. It was a very difficult time for our country, and I don't think we've really ever recovered from it. And I wanted to find out what Neil Sheehan had found.

I also knew what was going to happen when his book came out. He'd be on the Today show for six minutes. They'd probably talk about John Paul Vann's sex life. [Vann was an adviser to the regime in Saigon whose U.S. military career was derailed by a statutory rape charge.] I said, "This is an opportunity for us to do what [the networks] can't do." So I interviewed him for two and a half hours. We put Sheehan on every night for 30 minutes and then on the fifth night got him in the studio and opened the phone. We let people talk back to him. That's how we got into books.

It's been a magnificent evolution. The government finally got out of the way of over-regulating the cable television business. This thing blew open with the internet, so that now any human being in this country can dream about doing something in video and audio, and they don't have to ask anybody's permission.

I've always felt the idea of having a government employee sitting in an office at the [Federal Communications Commission] determining what's fair or not fair is a joke. What's fair today would not have been fair 20 years ago, and we're better off in spite of the fact that we don't like a lot of what we see or hear. It's better to have the freedom to say and do what you want to do and let the marketplace make that decision.

I can't stand the idea of regulation of content, and I can't stand the idea that government officials, including the Supreme Court, determine what we can see and not see. It's just the way I grew up. I'm not even sure I'm right. I'm sure a lot of people who loved the Fairness Doctrine [a defunct policy that required broadcasters to offer competing viewpoints on controversial public issues] would totally disagree with this. Back in the day, the right wing and the left wing [both] loved it, because they thought they could control the content. If it wasn't for the [end] of the Fairness Doctrine, you couldn't have started The Larry King Show. You had to match everybody's comment on radio with somebody else's comment. They wouldn't have taken a chance.

Do you worry that we're going through a new spasm of restriction, whether it's the attempts to bring back net neutrality rules or the effort to limit the legal immunity of websites and internet service providers under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act?

I'm too old to worry about stuff like that. Twenty-five, 30, 40 years ago I worried about it. It is the nature of Washington, D.C., that the cycles continue. No matter what we did 30 years ago, we're going to go back and do it again. When people get into power, they love control.

The cameras in the House and the Senate are under the control of the House and the Senate. No matter how hard we've tried to put our own cameras in there, they want to protect what people can see. It's the same way with the Supreme Court [refusing to allow cameras inside]. I love the Supreme Court. I think it's probably the best of the three branches of government. But the idea that they have hunkered down and said, "We're not going to let you see 75 one-hour arguments a year in which no decisions are made" just drives me crazy. There's really no excuse for it.

You've been trying to get cameras on the Supreme Court's oral arguments for years. You don't see any hope for that?

I have no hope in my lifetime that we'll get cameras into the Supreme Court. The new, younger members come into the Court, and they [seem amenable to the idea], but about six months in, they all of a sudden say, "Well, I've taken a look at it, and I think it's probably better off that we not televise proceedings." It's going to take somebody years from now who says, "It's time for the rest of the country to see what we do here in that little tiny courtroom."

You've mentioned that the Vietnam War was a shock to the system in many different ways, but especially when it came to the credibility of government and media. We now live in an age of "fake news" and hyperpolarization. Do you think things are better or worse or about the same when it comes to faith in media and politicians?

I'm not smart enough to know how to answer that question. As an individual I have far more information available to me today if I want to use it. There's really the 10 percenters in the United States that pay attention, who worry about the government and the future and all that stuff. The rest of the people just go on about their lives, and I think they've sadly learned to not trust their government.

[I recently interviewed] Amy Greenberg, a professor from Penn State, who did a book on the wife of James Polk, who was our president back in [the 1840s]. At one point in the interview I said, "Are you saying that James Polk lied us into the Mexican War?" She said, "Absolutely." And it just struck me: I mean, it's usually not quite that simple, but people have lied us into wars forever. With the situation with Vietnam, they were not able to sell us on the value of being there, but they lied us into it and lied to us during the war. It just so happened that I was in the Pentagon at the time, helping them lie. That had a big impact on me personally.

You see the polls all the time, and they're not very reassuring. The last poll I heard [said that] only 26 percent of the American people can identify the three branches of government. And that's disappointing when I think about the fact that we've been in business for 40 years. I would always think, along the way, that this might help people get to know more than they did before, but it doesn't seem to be working.

What will the next 40 years of C-SPAN look like?

This sounds a little bit pessimistic, but our next responsibility is to survive. The economic model is changing in front of our eyes. People are dropping cable. The kids don't watch television. They watch their phones, and our revenue stream is entirely based on the number of homes that are connected to C-SPAN. It used to be 100 million, but it's down to 88 million. Who's going to own these [cable companies], and will they be civic-minded? There's a lot more available through YouTube, websites, podcasts than we ever dreamed. We have got to continue to convince the people who pay our bills that we're worth $70 million a year—that we still have value.

This interview has been condensed and edited for style and clarity. You can listen to the full conversation, and don't forget to subscribe to the Reason Podcast.

*CORRECTION: This story has been updated to reflect the fact that Lamb is stepping down as CEO and ending his weekly programming but will still serve as executive chairman.

Show Comments (11)