The Case for Sanctions Fails at Every Turn

As pundits debate how much the Trump administration's penalties have contributed to Venezuela's economic crisis and as European governments move forward with a plan to trade with Iran in the face of U.S. sanctions reimposed on the Islamic Republic, it's time for some calm and straight talk about sanctions.

People who oppose putatively humanitarian military interventions are frequently charged with supporting genocidal tyrants. In the same way, people who oppose sanctions on disfavored regimes are often criticized as apologists for those regimes. Each charge is a non sequitur.

Suppose the American government sought to impose a general trade embargo on Bozarkia, a (fictional) country with a disturbing human rights record. No doubt some people would oppose the move because they happened to like the regime. But there would be good reasons to oppose sanctions on Bozarkia even if we found little or nothing to like about its government.

Sanctions are bad news for the same reasons trade barriers of all kinds are bad news. After all, they're designed to impede particular commercial relationships. If robust property rights are human rights that hold consistently across borders, and if these rights matter—because they promote prosperity, safeguard autonomy, reduce conflict, and so forth—then sanctions are obviously problematic, because they interfere with people's rights to use their property as they see fit.

An embargo on Americans' trade with Bozarkia would impede Americans' own property rights. It would involve the threat of force against the property and bodies of people who trade with that country. It would also, obviously, prevent Bozarkians from making unconstrained choices about the use of their property. For anyone who sees strong property rights as foundational to people's abilities to pursue their own projects, the obvious property-rights violations effected by sanctions should be sufficient to rule them out.

Property rights and the market exchanges they make possible enhance prosperity on an ongoing basis. Sanctions would intentionally interfere with Bozarkians' prosperity, but they would also interfere with Americans' prosperity, denying them the benefits that would otherwise come from trade.

Sanctions also limit people's associational freedoms. Sanctions on Bozarkia would keep Americans and Bozarkians from interacting with each other commercially. Again, if we value freedom of association, we have every reason to look skeptically at sanctions.

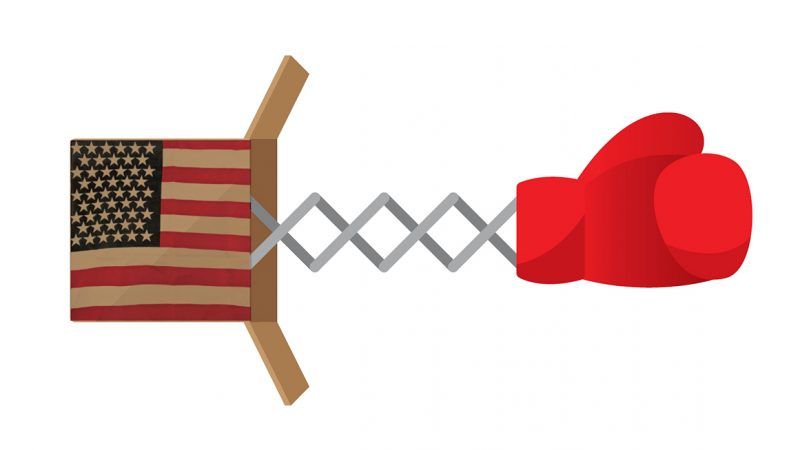

The U.S. government often structures sanctions specifically to interfere with the behavior of non-Americans. This is a kind of international bullying that seems designed to impose the will of a would-be global hegemon on unwilling subjects. It is not only an instance of egregious imperial overreach; it also encourages ill will, reduces the likelihood of international cooperation, and raises the possibility of aggressive pushback.

Indeed, sanctions are clearly instances of great-power meddling. (Countries that aren't great powers can hardly impose sanctions outside their own borders.) They're an especially ugly way for governments with military and economic influence to throw their weight around. To impose sanctions is to treat yourself as entitled to manage the lives of others.

Sanctions are deeply objectionable, too, because they represent purposeful attacks on others. Again, that's their point. They wouldn't work if they didn't undermine Bozarkians' welfare—not just by affecting the sizes of their bank accounts but also by impeding their access to the actual, life-enriching goods and services they could buy if trade were unimpeded. And choosing to injure real aspects of well-being is always cruel and unreasonable. It involves treating the welfare of Bozarkians as less important than, and therefore trumped by, our own putative policy goals.

Doing so might make sense if the goods we sought to realize really were more important than the goods sanctions deliberately attack. But they're not.

Bozarkians seek to realize all sorts of goods by engaging in trade—physical well-being via nutrition, aesthetic experience via entertainment, and so forth. And American policy makers seek to realize all sorts of goods by restraining trade. We can argue about what these are—the real goals may have to do with imperial dominance, though the nominal objectives may have to do with promoting the Bozarkian people's well being by freeing them from tyranny. In any case, different kinds of goods can't be quantitatively compared on a common scale. This means that the good things proponents of sanctions say they want to achieve don't objectively outweigh the good things sanctions exist to harm. Therefore, deliberately attacking Bozarkians' welfare in order to achieve these other goods just isn't reasonable.

Sanctions also enhance the risk of violence and full-blown warfare. Imposing sanctions is, in effect, an act of war, and sanctioned countries can be expected to respond violently against embargoes and other forcible attempts to interfere with peaceful trade. Whether or not they formally declare war, they will likely judge that war has been declared on them and act accordingly. Anyone who values peace should seek to cement trading relationships rather than undermine them.

Sanctions are frequently unfair because they are cast much more widely than their stated rationales would permit. Across-the-board sanctions on trade with Bozarkia affect not just Bozarkia's authoritarian leaders but also ordinary Bozarkians—in theory, the victims of their leaders' bad behavior whom sanctions are designed to benefit. Sanctions of this kind would impose costs on people who are not, in this case, responsible for the harms the sanctions purportedly seek to remedy. Indeed, a general embargo would seem likely to harm the most vulnerable people most severely, since those people lack the financial resources to cushion the blow sanctions deliver.

Unsurprisingly, then, sanctions often help inadvertently to legitimize sanctioned governments. Many Bozarkians may resent various choices made by their rulers. However, sanctions make them suffer. The imposition of sanctions—even in putative response to their government's misdeeds—would quite reasonably seem like bullying. Many Bozarkians might tribalistically identify with their government, which is, after all, made up of fellow Bozarkians. Seeing their country and even their government as being victimized by the United States, they would likely push back. More than that, they could be expected to rally around their leaders as their representative in the context of the crisis created by the sanctions.

Sanctions intended to undermine a bad government would thus likely end up strengthening it.

Sanctions also prevent the use of two crucial tools that can be used against authoritarian regimes. The brutality and unfairness of such a policy make it impossible for Americans to trade on an image of benevolence. The invitation to ally with us comes to seem more like the proverbial "offer you can't refuse" than like an attractive appeal to embrace attractive values and partners.

Meanwhile, sanctions directly interfere with cultural exchange in various ways, making it less likely that ideas, texts, music, films, and other drivers of cultural change will be available to people living under authoritarian regimes—with the result that there will be fewer spurs to social and political transformation.

Thus, sanctions seem rarely to undermine authoritarian regimes substantially. Even if the interference with property rights and the attacks on people's welfare that are essential to any sanctions regime were justified—which I believe they're not—sanctions fail to achieve what is often taken to be their ultimate goal.

Sanctions proponents sometimes cruelly suggest that they are intended to make people suffer enough to overthrow their government and install one sympathetic to U.S. interests. But sanctions will often prompt people to support embattled governments more, and people subjected to sanctions seem strikingly unlikely to rally to the side of the power responsible for increasing their suffering. Even if they do overthrow their government, what are the odds that they'll respond positively to an interfering power that caused poverty, loss, and death by means intended to manipulate them?

Everything I've said so far assumes that sanctions are well-intentioned. But the rationales characteristically offered for sanctions can hide bad motives. Humanitarian rhetoric can provide excuses for economic policies designed to benefit domestic political interests or to foster imperial goals. As long as the policy tool of sanctions is on the table, fallible governments can hardly be expected to consistently employ that tool in anything like a virtuous way.

Imposing sanctions means interfering with people's freedom to trade and their freedom of association. It means undermining not only the prosperity of the people who live in the target country but also our own prosperity. It means deliberately, and therefore unreasonably, attacking various aspects of people's welfare. It means harming them as a way of controlling them. It means increasing the chance of violent conflict and eliminating factors that make conflict less likely. It actually props up bad governments and limits efforts to undermine them. It's a classic instance of international bullying. And it is all too likely to be used as a means not of humanitarian assistance but rather of imperial mischief.

Sanctions are cruel, ineffective, and unreasonable. We should unequivocally reject them as tools of international policy.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

This article is laughably naive. If your fictional country prevents you from actually engaging in real free trade with its people, then you are just propping up an evil government and actually making it harder for the people in the country to dethrone their despot. Using the simplistic logic in this article, it is okay if I sell sarin gas to a horrible regime because "free trade". Who cares about the obvious ramifications of that decision? All the moralizing in the world doesn't change the fact that allowing that free trade is objectively horrible for the people under that regime.

Exactly. Author fails to see that sanctions aren't denying the offending country's people anything, but rather the corrupt autocratic regime that would clearly benefit from unimpeded association. I don't always approve of sancions, but this article was a shitty analogue. Also, #BozarkiaForever

People like this author dont even care if the trade is actually "free trade" where all trading partners play by the same rules, even if they are simple and unwritten.

Unilateral trade will do too, as long as the USA is the nation who can get cheap shit from slaves working for the tyrants.

If you think that the US benefits very much from slave labor, you're a moron. The biggest trading partners of the US are China, Mexico, and Canada. Which one of those places is employing slaves?

USA Prison Industrial Complex.

Chinese huge prison industrial complex.

There you go moron.

^^^ This ^^^

Yup number of prisoners per 100000

US 737

China 118

Russia 615

Does that count China’s re education camps?

There aren't a ton of actual slaves anymore, although the prison industrial complexes are a thing... But there are a lot of shit working conditions. I tend to believe if the shit conditions are less shit than they would have otherwise, it's fine.

But, I also don't believe we should be offering favored status to nations that actively want to slit our throats...

Agreed. This reads like a bad high school writing assignment on ‘why sanctions are really mean’.

So this article effectively states do not use the three main tools of foreign policy. However, it makes no mention of any sort of remediation to the problem.

Gary, I'm listening, but you need to actually make a case to replace some other tools with those you object.

The Anarchy-Land that these people want is what humans moved away from millennia ago. The strong man wins.

These Anarchists wont even pool their money and purchase an island or some other land to start Anarchy-Land. They want the USA to burn. They're cowards.

The tool is free trade and exchange. Just look at Iran. Plenty of young people are saying fuck you to the regime, refusing to wear their hijabs, and starting a massive shift.

Was it because of sanctions? No.

Was it because of a bombing campaign? No.

It was actually because they saw twitter, instagram, etc. They see how much better Americans' lives are, and are now starting to shift their own country to match.

Why do you think the Iranian govt is trying to crack down on twitter?

And in another 40 years, I'm sure they'll make some progress

Shit, why not just sell the Ayatollah nuclear technology then?

Do you think if we'd helped them be vastly wealthier economically that they'd be more or less pissy?

I think China proves without a doubt that the old theory that economic freedom leads to political freedom is not accurate. So does Singapore. If South Korea or Taiwan had remained harder edged I don't think people there would have minded much either.

So I think the TRUE answer is that sometimes you can't force a result with ANY means at your disposal. Sometimes ya can, sometimes ya can't.

War with Bozarkia, obviously, is the Libertarian Free Trade approach. Because sanctions are bad

Just as long as we sell them the arms to fight us, we will remain on the right side of history

So. it's 1939 and the NSDAP in Germany want to buy P38s from the plants in California. You sell them, right? Also large stocks of strategic materials, more than they could possible need for several years.

Peace in our time!

It's why Anarchy does not work for 99.999999999% of Americans.

We want peace and live in the real World.

Sometimes you have to stand up to the tyrants of the World since they wont play by the same rules as the rest of us. Part of the reason for these United States was for the common defense. Anarchists hate the USA as a Constitutional Democratic Republic.

Yeah, and fighting Hitler only helped Stalin. Fighting Hirohito only helped Mao. Stop acting as if WW2 had a good ending. Interventionism always, yes ALWAYS, fails.

always cycling through the socks.

So responding to Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor is interventionism? Or defending legitimate American interest in the Pacific was interventionism? I'm sure all those who were reached by the American led allied forces at Buschenwald and others viewed America action as intervention.

Shame on us for intervening in Hawaii's affairs

What if we'd been smart enough to do what Patton and Churchill wanted, IE continue riding those tanks on into Moscow? Or perhaps forced capitulation when we were the only ones with nukes?

It's essentially the sunk cost concept... But I think it is a valid one sometimes. The way we allowed the end of WWII to play out was bullshit. I don't think it was a horrible idea to fight the Axis... But on that same principle, given our footing, it WAS a horrible idea to NOT take out the USSR and Mao. Too much had been invested to not go that extra little bit to have a proper good result.

Sanctions also enhance the risk of violence and full-blown warfare. Imposing sanctions is, in effect, an act of war, and sanctioned countries can be expected to respond violently against embargoes and other forcible attempts to interfere with peaceful trade.

NO sanctions are NOT an act of war (even with your caveat "in effect"). International law does not support your claim nor does any legitimately recognized casus belli for war in the last 100 years.

Embargoes are considered an act of war because you are actively blocking ALL trade into the target country.

Sanctions are disincentives for trade that goes into a target country from the initiating nation and nations that choose to do business with the initiating nation. All nations can end trade relationships with the initiating nation and do as much business as they want with the target nation.

Trying to push your Anarchist agenda that any trade restrictions are, in effect, acts of war is ridiculous. If you are teaching students this claim, you are literally horrible at your job.

Okay, what percentage of trade needs to be restricted to not be an act of war? 99%? 90%? 50%?

Yes, all trade restrictions are, by definition, acts of war.

Your definition of "act of war" fell off.

So, since Japan has restrictions on US ag exports we should nuke Hiroshima again? Maybe launch a few missile strikes against Europe because they severely restrict US grain and meat exports?

What do you consider the massive institutionalized industrial espionage, forced IP transfer, patent infringements, and tariffs that China has been foisting upon us? If it is war, how many decades are we supposed to let go by before we fight back?

LOLOLOLOL

You're so detached from reality it's not even funny dude.

Look, whether you like it or not, strategic control of trade resources has always been a thing. Sometimes it was for purely economic reasons, other times for political ones. Either way, within reason, it is NOT an act of war.

It is certainly a form of pressure... But conflating the two is like how an SJW considers a mean word to have the same weight as shooting somebody in the dick with a 12 gauge. Any sane person can see there's a gradient, it's not black/white.

I agree with the general observations made in this article, but I do have a couple of reservations:

1) Sanctions are sometimes successful, but it depends on what you're trying to accomplish.

On Friday, I linked to a story about Putin and his cronies at Rostec withdrawing operations from Venezuela. In addition to doing surveillance type contracts for the Venezuelans, Rostec was also training and maintaining military helicopters for the Maduro regime. They were also building a Kalashnikov factory in Venezuela. If you read the story, the reason the Russians are withdrawing their personnel and shutting down operations is because they can't get paid by the Maduro regime and see no likelihood that they will be paid in the future. Meanwhile, both Rostec and the Maduro regime are subject to sanctions. No, sanctions won't drive Maduro from power, but they have helped drive Russian defense contractors out of the country who were supplying Maduro with expertise and hardware necessary to maintain control.

http://www.wsj.com/articles/in-a-blow-to-maduro-russia-withdraws-key-defense-support-to-venezuela-11559486826?

2) From a moral standpoint, sanctions are at best the lesser of two evils, but that means they are sometimes really are the better alternative to something worse.

The same thing can be said of war.

Dropping bombs on other countries, invading, and occupying them is generally a bad things to do from both a strategic and a moral perspective, but it can be justified (in a variety of situations) within the context of Congress exercising its proper authority to declare war and a moral case for the war in question like self-defense or even for (perhaps misguided) humanitarian reasons.

If wars can sometimes be a necessary evil, why can't sanctions, in which bombs are dropped on anybody and no one is occupied, be a lesser necessary evil--especially IF IF IF and when they're the alternative to war?

As tiny and limited government is a necessary evil, so sanctions can be to discourage tyrants from using American trade to get so strong that they can hurt American long term interests.

One American long term interest is that South America and North America remain relatively stable. Nothing ruins international trade like massive armed conflict in the same area of the World.

Yup. As with war, they are things that should be used sparingly, and only when it makes sense. But there is a place for both war and sanctions.

[…] Chartier makes a very compelling case against the use of economic […]

I'm assuming that Reason is now withdrawing its objections to arms sales to Saudi Arabia. I know, I know, that's different, because reasons.

lol

[…] Chartier makes a very compelling case against the use of economic […]

"Sanctions are cruel, ineffective, and unreasonable."

Ahem. "Ineffective?" South Africa.

South Africa has one of the most failed economies in the world.

Apartheid and racism, corruption, all of that matters. All of those still exist. To say that sanctions helped, well prove that.

Ummmm... Their economy actually wasn't bad back in the day. They were the wealthiest country in Africa, and outside of the tribal hinterlands their average incomes were basically up to 1st world standards.

For better or worse, our sanctions DID wreck their economy to a large degree, and was a major reason why they finally caved and allowed majority rule. Funny thing is majority rule has probably created more economic problems for the nation than they would have has living in complete isolation! LOL

As I said above, sanctions should be used sparingly... But there is a time and a place for them. Just as there is a time and a place for actual war.

Sanctions are just one point along a line that represents pressure against another nation. Especially if you get lots of other nations on board, it can amount to quite a lot of pressure, but without outright violence.

I think most times we've used sanctions were doomed to fail... But sanctions where other nations join us, and it's an especially vulnerable regime... They can achieve things.

Whether or not we should bother is the question. If tyrant XYZ wants to hose their own people, should we care? I'm often inclined to say no, provided they're not trying to become a nuclear power or something. When a belligerent nation has ill intent that they might manifest towards us directly via violence, that is another thing.