The Wall Won't End Pot Smuggling at the Border. Legalization Will.

Pot is bulky and pungent. That makes it difficult to conceal in, say, a suitcase or a truck. For that reason, marijuana traffickers tend to avoid legal ports or entrances, preferring instead to traverse the expanses of deserts and canyons where Border Patrol agents are often the only signs of human life. To the extent that other drugs cross outside normal entry points, they are most often hitchhikers along for the ride with the weed. In 2013, for example, Border Patrol agents seized 274 pounds of marijuana for every one pound of other drugs.

So for those familiar with the history of drug smuggling, there was a dog that didn't bark in Donald Trump's early January Oval Office address, which was intended to frighten Americans into supporting a border wall and give him leverage to end the shutdown. While Trump described the southern border as "a pipeline for vast quantities of illegal drugs," he only specifically mentioned "meth, heroin, cocaine, and fentanyl"—all drugs that typically come in through formal points of entry. He did not speak of what has been, for most of living memory, the most-smuggled item over the Mexican-American border: marijuana.

Pot, and the impoverished undocumented immigrants who often bring it, are no longer flowing across the border at the rate they once were. This decline has virtually nothing to do with expensive security innovations at the border and everything to do with legalization in the United States. If it were any other industry, one imagines the president would be delighted: When it comes to pot, customers prefer to buy American.

A Century of Fecklessness

President Trump is far from the first politician to use drug smuggling to justify greater border security. During the 1920s, the "need" to combat smuggling served as a primary justification for the creation of the Border Patrol. In 1922, the commissioner general of immigration warned that "dope, liquor, Chinese, and alien smuggling has become a lucrative business and is being carried on by international gangs in which there have been found the hardest, most daring, and cleverest criminals." These nefarious forces, he added, were "backed by no limit of funds and possessed of the highest powered vehicles."

In 1924, Congress responded to these concerns and the need to enforce new restrictions on legal immigration by creating the Border Patrol. During alcohol Prohibition, the agency went on to confiscate millions of quarts of liquor. Year after year, the immigration commissioner's reports requested more agents, vehicles, and even airplanes to compete with the traffickers.

Then, in December 1933, national Prohibition was repealed. Though some states continued the pernicious policy, the illicit smuggling of booze immediately dropped by 90 percent. By 1935, liquor importation at the border, and the grave warnings over it, had disappeared entirely.

The calm, however, was short-lived.

Barely two years later, Congress enacted a nationwide ban on marijuana through the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937. Suddenly, the Border Patrol began touting the "drive against narcotics"—in particular, "Mexican marihuana"—as the justification for spending more money to "secure the border." With the official launch of the "war on drugs" under President Richard Nixon, when marijuana was classified as having "no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse," the Border Patrol focused even more attention on drug smuggling. In 1972, the Immigration and Naturalization Service announced that "because of known alien involvement in illicit drug traffic, Service officers have directed increased attention to the detection of possible drug violations."

Today, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) spends billions of dollars a year on drug interdiction efforts. In addition to its 20,000 agents, the Border Patrol has constructed 650 miles of fencing and "vehicular barriers" designed to stop drug runners across the deserts. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has nearly 1,500 canine units and a coast-to-coast surveillance network that includes a fleet of Predator drones. Despite this costly effort, the DHS inspector general concluded in 2016 that the department "could not ensure its drug interdiction efforts met required national drug control outcomes nor accurately assess the impact of the approximately $4.2 billion it spends annually on drug control activities."

Foretelling the doom of Trump's wall, the Border Patrol discovered on average more than one drug smuggling tunnel from Mexico every month from 2007 to 2010, even as it built out hundreds of miles of security fences along the border. This was in addition to more than 300 holes per month that people were putting in the fences. When smugglers weren't going under or through the barriers, they were literally driving over them on ramps—a fact uncovered when an unlucky smuggler's SUV pinned itself on top of a fence. Even that hang-up didn't stop the innovative criminals from making off with the dope.

Pot Smuggling Plummets

Drug smuggling moves in an underground economy, which necessarily means rigorous formal statistics are hard to come by. Importers understandably make no publicly available reports, so the true scale of the enterprise can only be estimated indirectly, when government agents bring portions of the invisible market to light. The absolute amount of drugs that smugglers bring into the country is many times greater than the amount seized, but drug seizures can serve as a proxy for changes in the flow of drugs. In the absence of other developments, a significant increase in drug seizures likely indicates an increase in the flow.

If the government cracks down on the border, seizures will increase even if the same quantity of drugs is being smuggled. But focusing on the amount seized per agent controls for the level of enforcement activity.

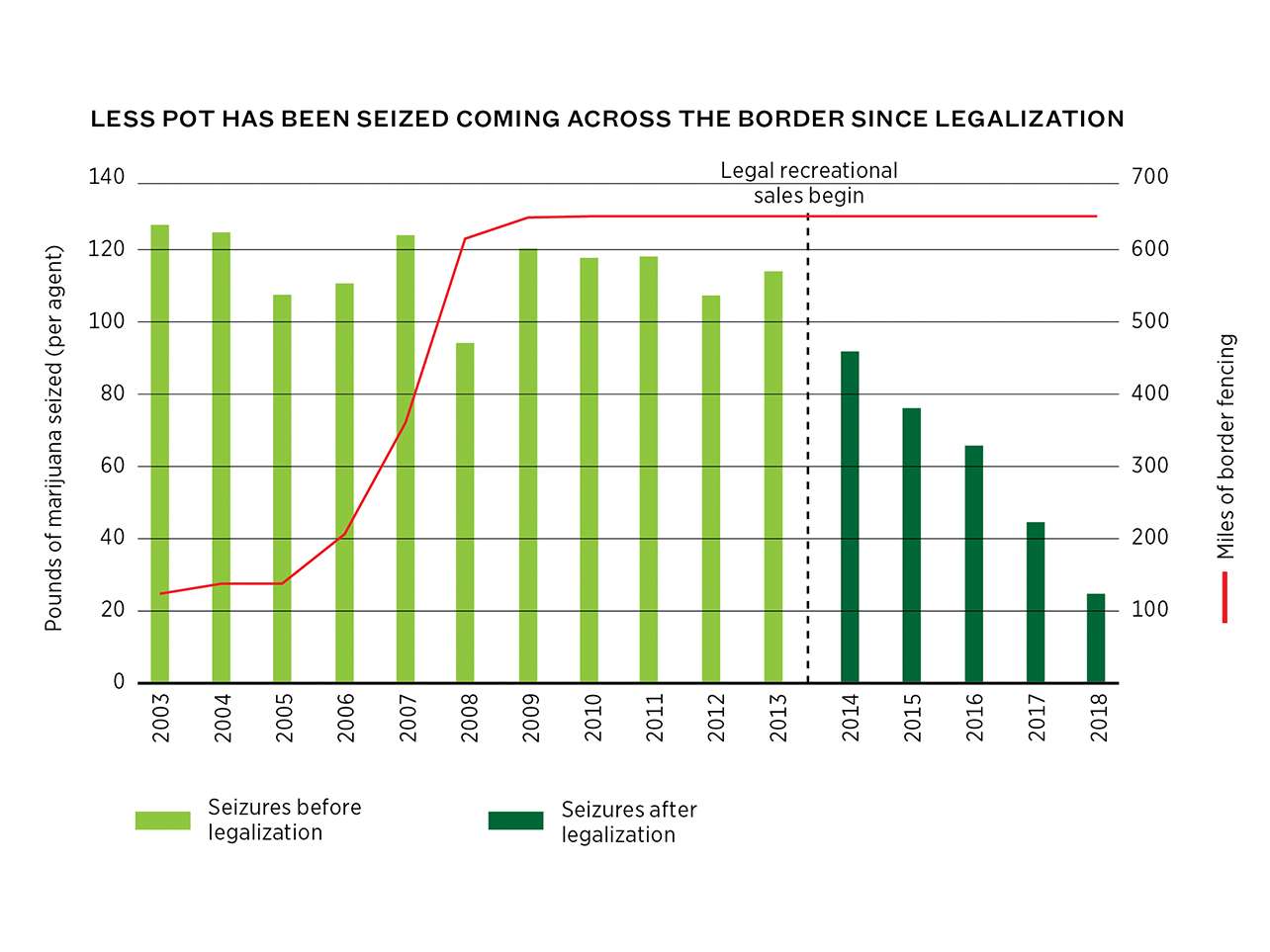

From 2003 to 2009, Congress made massive investments in border security. It nearly doubled the number of Border Patrol officers from 10,717 to 20,119, and nearly all of the existing border barriers were constructed during that period. But the amounts of marijuana seized per agent remained virtually constant, with the average agent confiscating about 115 pounds annually throughout.

In 2013, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) concluded that marijuana smuggling had "occurred at consistently high levels over the past 10 years, primarily across the US-Mexico border" and indicated no particular hope of halting the flow. From 2010 to 2018, enforcement remained roughly constant—no new hires or fences—but something strange happened in 2014: Seizures per agent began to decline. By the next year, they were down by a third. By 2018, the average Border Patrol agent was seizing just 25 pounds for the entire year, or less than half a pound per week—a drop of 78 percent from 2013. Even within 2018, monthly seizures during the first quarter of the fiscal year were a third higher than those in the remainder of the year.

Although it is the most important agency for interdicting marijuana, the Border Patrol isn't alone in witnessing the sudden disappearance of pot smugglers. Its sister agencies in the DHS—Air and Marine Operations, the Coast Guard, and ports of entry inspectors with the Office of Field Operations—saw similarly large drops in marijuana seizures. While full 2018 figures aren't yet available, all DHS agencies together seized 1.8 million fewer pounds of marijuana in 2017 than they did in 2013—a decrease valued by the department at about $1.5 billion.

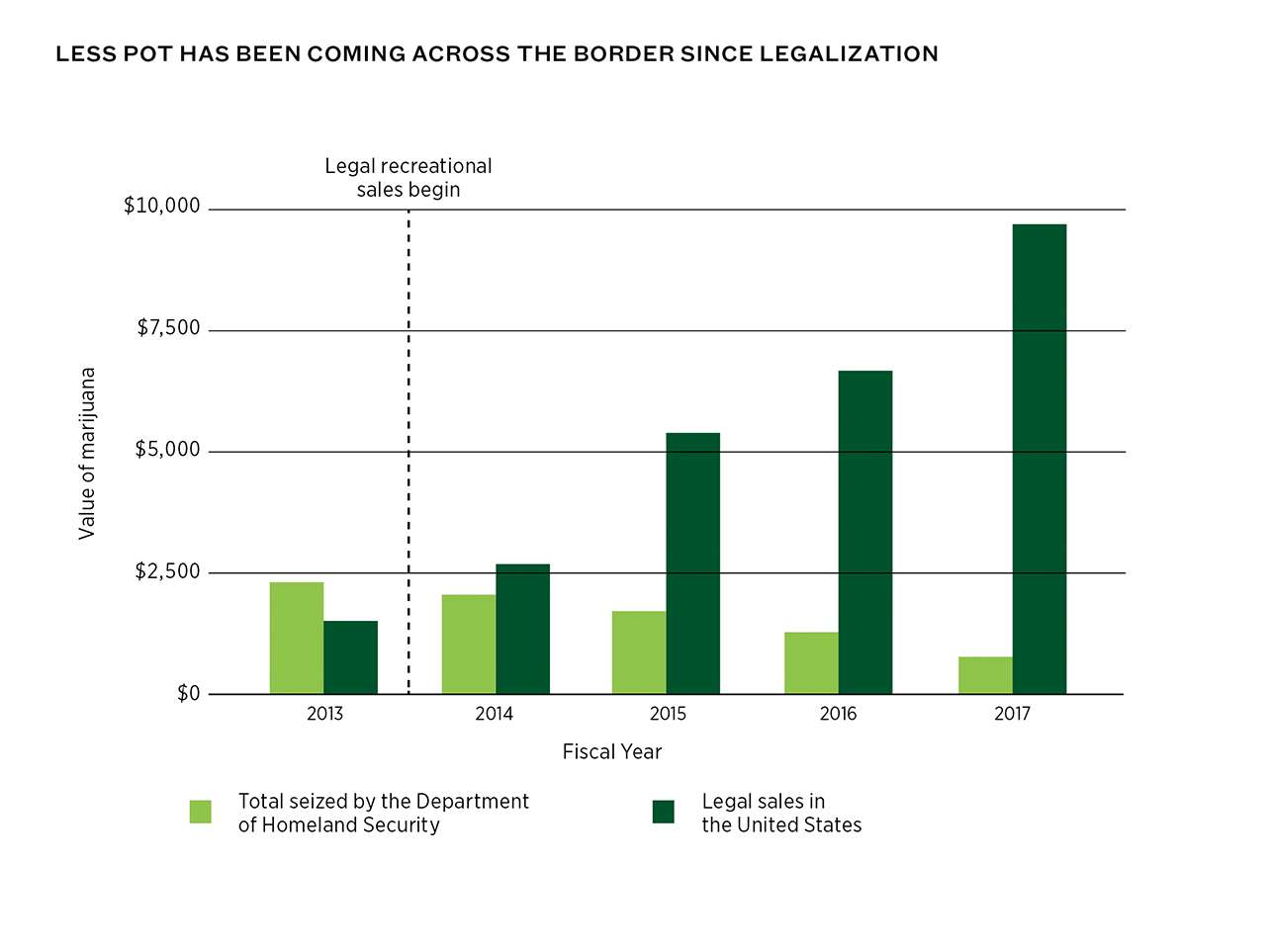

Legalization Does What Fences Can't

The mysterious disappearance of illicit weed did not coincide with any significant changes in use of marijuana by Americans. Indeed, slightly more people told government surveyors that they had used marijuana during the prior year in 2017 than in 2013, continuing a trend that started before legalization. But the disappearance did coincide with a nearly sevenfold increase in legal sales, according to estimates from Arcview Market Research. A relatively small number of such transactions had gone on prior to 2014 under the auspices of medical use, but full legalization jump-started the industry.

It was in 2014 that Colorado and Washington state permitted the first legal sales of marijuana for recreational purposes. Oregon officially joined the pot party in 2015, Alaska in 2016, and Nevada in 2017. California opened fully legal dispensaries in January 2018. Massachusetts did the same in November. And Michigan and Maine have similar plans to be implemented in 2019 and 2020.

By September 2018, one in six Americans lived in states with legal marijuana sales. After Michigan and Maine open their dispensaries, nearly one in four will do so.

Some opponents of legalization doubted the black market would dry up. At least in Colorado, they were wrong. A study commissioned by the state's Department of Revenue found that a "comparison of inventory tracking data and consumption estimates signals that Colorado's preexisting illicit marijuana market for residents and visitors has been fully absorbed into the regulated market." States with more taxes and regulations have seen less success, but except in heavily regulated California, legalization has been accompanied by major increases in legal sales and moves away from the black market.

Within the year, two-thirds of Americans will live either in or next to states where marijuana is legal. Given the ease of travel, these legal sales can end up supplying places where pot prohibition is still the law of the land. The Colorado study noted that "legal in-state purchases that are consumed out of state" are likely occurring. How far these purchases travel is difficult to know, but even before Washington and Colorado implemented legalization, a study by the Mexican think tank IMCO predicted that U.S. domestic weed would quickly replace the imported stuff, since it would likely be more expensive to smuggle the plant from Mexico than to ship it from those two states to any other state except Texas.

Colorado authorities working with the DEA have made several high-profile busts of interstate smuggling rings. "Residents of Colorado, and people that I'll call 'transplants to Colorado,' are moving here, becoming involved in the marijuana industry with the expressed purpose of hiding their illicit proceeds and their illicit activities in plain sight under some of the laws that we have," said Barbra Roach, head of the DEA's Denver division, in March 2017 after breaking up a smuggling operation that involved shipments to Illinois, Missouri, Arkansas, and Minnesota. Oklahoma and Nebraska even sued Colorado in an attempt to stop legalization there, a case the Supreme Court declined to hear in 2016. But no one disputed that legally grown Colorado marijuana was making its way to other states.

The increased supply of U.S.-grown cannabis has undercut demand for the Mexican product and harmed marijuana farmers south of the border. Growers in Mexico have reported declines in wholesale prices of 50–70 percent in recent years. "If the U.S. continues to legalize pot, they'll run us into the ground," one marijuana producer in Mexico told NPR in 2014. "We're only getting $40 a kilo. The day we get $20 a kilo, it will get to the point that we just won't plant marijuana anymore."

That is exactly what has happened as the flood of higher-quality marijuana from the U.S. has begun competing with the illicit plants from Mexico. CBP itself has hypothesized that one explanation for the decline in pot seizures since 2014 could be that "legalization in the United States [h]as reduced demand" for imported cannabis.

Two Failed Government Wars

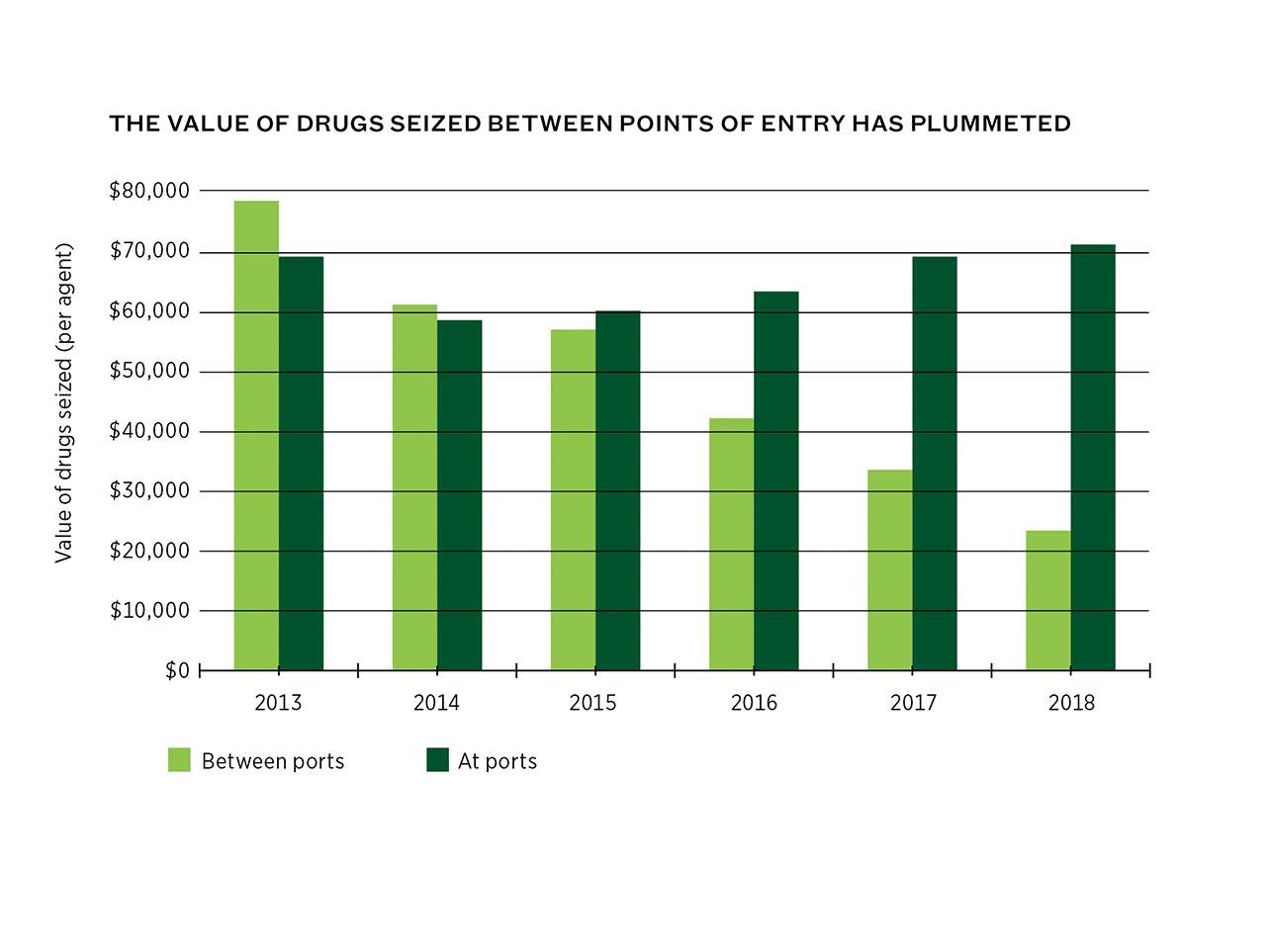

Marijuana, thanks to its volume and odor, has traditionally been the primary drug smuggled into the U.S. between official points of entry. Those routes are risky and expensive; thousands of migrants have died in the deserts trying to use them. This is why drug cartels primarily rely on U.S. citizens to bring more easily concealable drugs, such as heroin, into the country in their baggage or on their person through normal ports of entry. They already have the right to enter, which reduces the reason for law enforcement to stop them.

Given this dynamic, the decline of marijuana smuggling has made the Border Patrol, which focuses on areas between ports, of much less use to drug warriors. In 2013—before the first state legalization laws took full effect—the average Border Patrol agent seized drugs that were more valuable than the average inspector at ports of entry, based on the agency's own valuations. With the disappearance of marijuana coming across the deserts, the value of all drugs seized by the Border Patrol declined 70 percent from 2013 to 2018. Today, the average port inspector seizes drugs three times more valuable than those seized by the average Border Patrol agent.

The difference is even more dramatic for "hard drugs": 87 percent of the meth, cocaine, heroin, and fentanyl seized by Border Patrol agents or port inspectors in 2018 came in through a point of entry. DHS valued its nonmarijuana drug seizures at official entrances at $1.5 billion, compared to just $216 million for those by Border Patrol. In other words, Trump's border wall won't touch the vast majority of hard drugs entering the country, despite him singling them out in his Oval Office speech. And even if it did, it would be no more likely to succeed than the fence, agents, or cameras were in combating marijuana or alcohol.

The cartels, reeling from the loss in marijuana income, have attempted to replace pot with other drugs, but that proved easier said than done. The total value of all drugs seized at the border—at ports or otherwise—has fallen by a third since 2013. So cartels that invested significant capital in the marijuana trade are attempting to make up the losses in another way: by using their drug tunnels to smuggle immigrants across the border. The profit margins for moving humans are so small, and the effort has such a large footprint, that only desperate times would justify using tunnels to bring them in.

"While subterranean tunnels are not a new occurrence along the California-Mexico border, they are more commonly utilized by transnational criminal organizations to smuggle narcotics," a CBP official stated after the agency busted a group of 30 immigrants emerging from underground in 2017. "However, as this case demonstrates, law enforcement has also identified instances where such tunnels were used to facilitate human smuggling."

This shift allows Trump to point to the other purpose of his proposed wall: to keep migrants out. But just as the fences failed to keep out drugs, there is no evidence that a wall would keep out people.

Indeed, the border brings together two failed government wars in one place: the war on illegal drugs and the war on illegal immigrants.

When Congress enacted the first draconian caps on legal immigration in the 1920s, illegal entries became a regular occurrence for the first time. Everyone understood what had created the problem—the ratcheting back of legal immigration—and immediately made the comparison to alcohol Prohibition. In 1926, the immigration commissioner wrote that "as a consequence of more recent numerical limitation of immigration, the bootlegging of aliens…has grown to be an industry second in importance only to the bootlegging of liquor."

While the war on booze has ended, the wars on drugs and illegal immigrants have continued at full speed. The origins of these efforts have long since receded from the national memory, and people view illegal immigration and drug smuggling like hurricanes: as natural phenomena that the government manages or mitigates rather than causes. But as the effects of marijuana legalization prove, smuggling is not caused by traffickers; it's caused by government.

Fixing Illegal Immigration

The story of widespread pot legalization contains a clear lesson for immigration policy.

For nearly a century, Americans have been told that illegal immigrants ignore the law and bypass the legal options. But they aren't ignoring the law. They are acknowledging what it says: that they are barred from coming to this country. And they aren't bypassing legal options, because no such options exist for them.

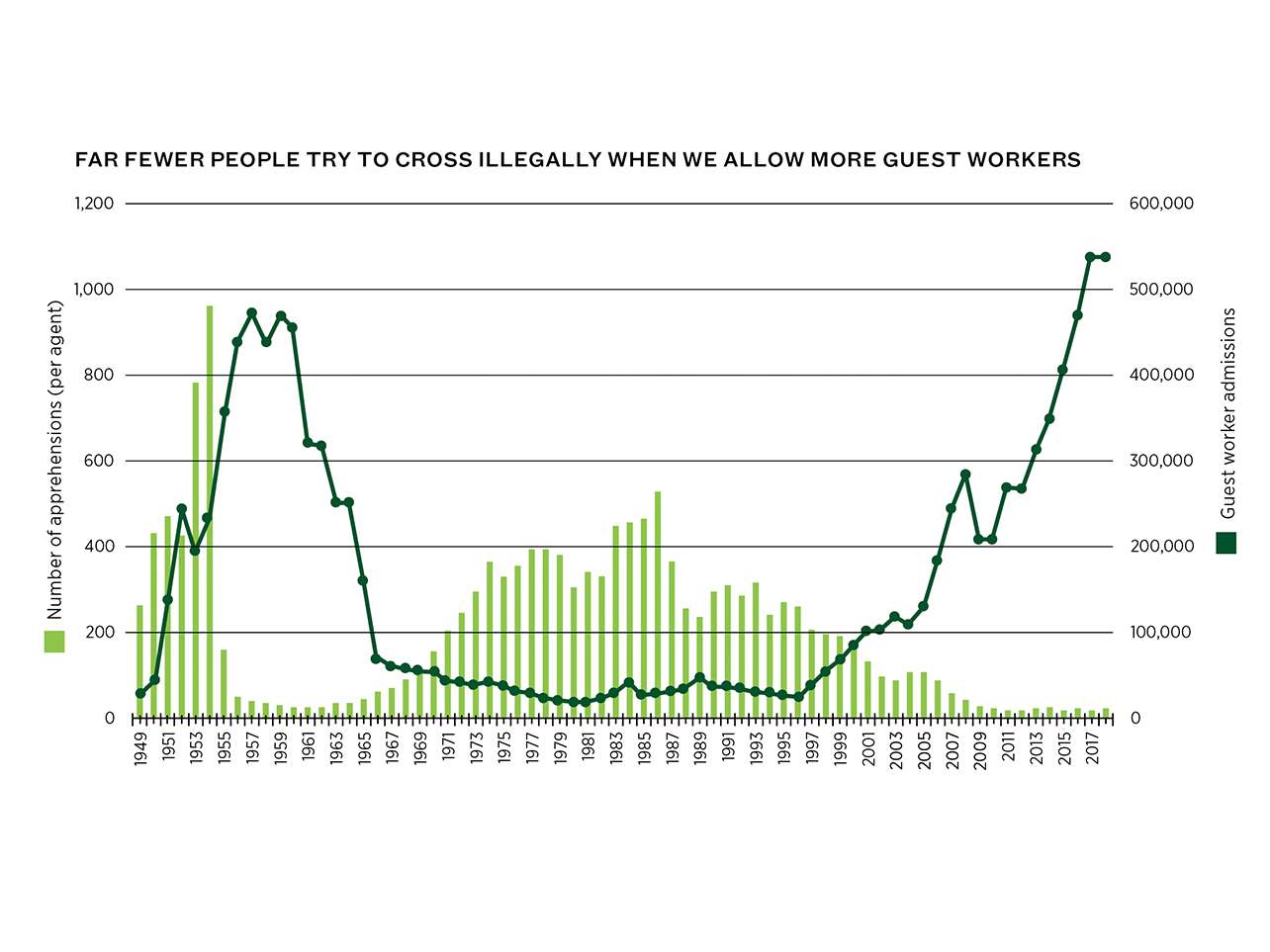

Whenever aboveboard options do appear, the problem dissipates. The more unskilled guest workers that the United States allows in legally, the fewer illegal immigrants appear at the border to be caught. In the seven decades from 1949 to 2018, the average Border Patrol agent apprehended 86 people annually in years when guest worker entries were greater than 200,000. In other years, the average was 269 people per year—three times as many. Since 1986, thanks to the lack of a quota on agricultural workers, the total number of legal guest workers in the United States has increased twentyfold to 536,634; meanwhile, the average agent now apprehends 97 percent fewer people than he did 30 years ago.

Legalization works. More legal immigration, like more legal pot, means less illegal activity. The problem with America's immigration laws is that we make it almost impossible to come here while following the rules. While those guest worker admissions are impressive, nearly all of the increase has gone to Mexicans, because regulations require U.S. employers to pay for employees' round-trip travel, which incentivizes hiring the closest candidates. Central Americans therefore have a much harder time finding legal entry. No wonder they constituted the majority of apprehended migrants in 2018.

Even for Mexicans, lesser-skilled workers without U.S. citizen family members have no legal way to come to the country permanently or even to work in year-round positions. Businesses can't sponsor their lesser-skilled guest workers for permanent residence (lawmakers want them to have to leave), and since 1990, Congress has allocated just 5,000 green cards per year for employees of U.S. businesses who lack college degrees—a infinitesimal fraction of the nearly 11 million immigrants here illegally today.

For people fleeing violence south of the border, the situation is even bleaker. Their only legal option is to somehow get to the U.S. and request asylum. The government is supposed to process anyone who asserts a fear of returning to her home country at a legal port of entry, but the Trump administration is turning them away, saying it's prioritizing other travelers. The result is that most asylum seekers are now crossing illegally and turning themselves in. Even then, only people with a "well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion" can actually receive asylum. Reasonably believing that you're going to be murdered isn't enough.

The answer to these problems is the same as the answer we've stumbled upon to marijuana smuggling: Legalize it. Make it simple. Get rid of as many regulations as possible so that people truly have the option to "follow the rules." If peaceful people want to put their talents to work for Americans, let them. If someone is fleeing a fire somewhere in the world, America doesn't need to put it out—but we shouldn't block the fire escape. Until the government learns that its own policies are the causes of illegal immigration and drug smuggling, the problems will continue. Legal weed offers a blueprint for a better way forward.

Sources, Figure 1: U.S. Department of Homeland Security Ofce of Inspector General, "Independent Review of the U.S. Customs and Border Protection's Reporting of Drug Control Performance Summary Report," 2008, 2011; Customs and Border Protection, "Sector Profiles," 2012–2017; Customs and Border Protection, "Enforcement Statistics FY 2018," August 31, 2018; Border Patrol, "Staffing Statistics," December 12, 2017.

Sources, Figure 2: Arcview Market Research, The State of Legal Marijuana Markets, 1st–6th editions; author's calculations based on drug valuations and amounts from Customs and Border Protection, "Local Media Releases," 2013–2018; U.S. Department of State, "Narcotics Control Reports"; Customs and Border Protection, "Enforcement Statistics FY 2018," August 31, 2018; Air and Marine Operations, Reports and Testimony, 2013–2017.

Sources, Figure 3: author's calculations based on drug valuations and amounts from Customs and Border Protection, "Local Media Releases," 2013–2018; Customs and Border Protection, "Enforcement Statistics FY 2018," August 31, 2018.

Sources, Figure 4: U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, "General Collection," 1949–1995; U.S. Department of Homeland Security, "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics," 1996–2017; Immigration and Naturalization Service, "History: Border Patrol," 1985; TRAC Immigration, "Border Patrol Agents," 2006; Border Patrol, "Staffing Statistics," December 12, 2017.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Wall Won't End Pot Smuggling at the Border. Legalization Will.."

Show Comments (58)