In Giant Cross Case, Justices Struggle to Clean Up a 'Dog's Breakfast' of Confusing Precedents

The alternatives suggested by defenders of the monument do not seem much better.

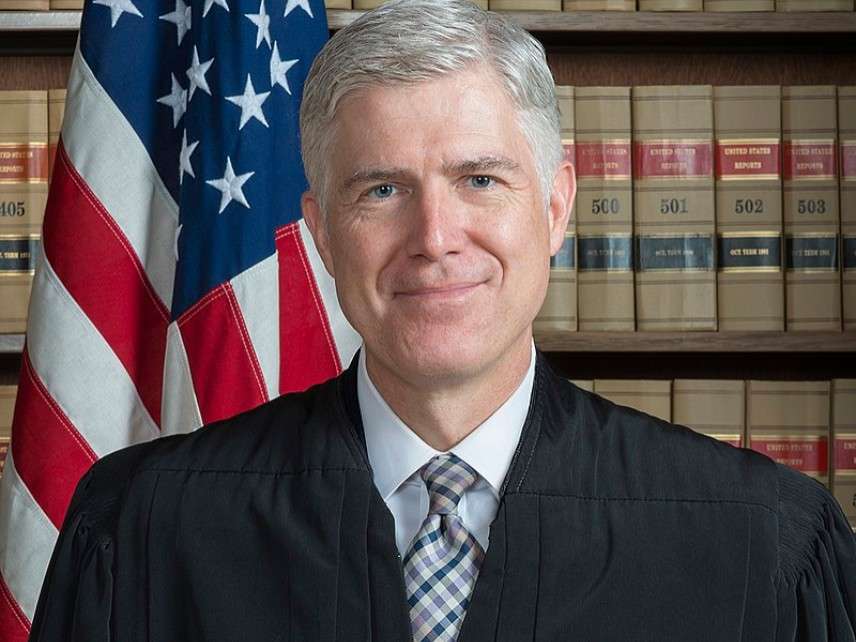

Yesterday's oral arguments in a Supreme Court case involving a giant cross vividly illustrated how hard it is to define "an establishment of religion" once you go beyond the clearly prohibited practice of forcing people to support a government-backed church. Justice Neil Gorsuch twice referred to the highly subjective test described in the 1971 case Lemon v. Kurtzman as a "dog's breakfast." But the alternatives suggested by the lawyers defending the cross, a state-owned World War I memorial that sits in the middle of a busy highway intersection in Bladensburg, Maryland, do not seem much more promising.

Under the Lemon test, a government-sponsored display violates the First Amendment's Establishment Clause if it lacks a secular purpose, if its "principal or primary effect" is to advance or inhibit religion, or if it fosters "an excessive government entanglement with religion." In 2017 the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit concluded that the Bladensburg monument ran afoul of the second and third prongs.

Neal Katyal, representing the state commission that is responsible for the monument, told the justices the test should be "whether or not there's an independent secular purpose," which suggests that the first prong of Lemon is the only one that matters. Later he revised that position, saying the real issue is the display's "objective meaning."

In divining the meaning of the Bladensburg cross, Katyal argued that four facts make it sufficiently secular to pass constitutional muster: It has been accepted as a war memorial for 93 years; it has an American Legion symbol at its center and the words "Valor, Endurance, Courage, Devotion" on its base; it includes a plaque of dead soldiers' names but "not a single word of religious content"; and it is "situated in Veterans Memorial Park alongside other war memorials" (although "alongside" is rather misleading, since the cross is isolated from the other monuments, which are across a highway and 200 feet to half a mile away).

These details, in Katyal's view, distinguish the Bladensburg cross from an Indiana monument that a federal appeals court deemed unconstitutional in 1993: "a huge cross with Jesus Christ nailed in the center of it in a public park." That cross, which bore the initials INRI, representing the Latin for "Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews," also was presented as a war memorial. But "the 7th Circuit said that is unconstitutional," Katyal said, "and we agree."

The American Legion, which is also defending the Bladensburg memorial, sees things differently. The organization's lawyer, Michael Carvin, argued that all such monuments are constitutional. He urged the justices to apply the "coercion test" that it used to uphold Christian prayers before town board meetings in the 2014 case Town of Greece v. Galloway. That test, Carvin said, "prohibits tangible interference with religious liberty, as well as proselytizing."

The justices immediately pointed out the difficulties with that approach. If the Establishment Clause is all about preventing "tangible interference with religious liberty," Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wondered, how is it distinct from the Free Exercise Clause? Gorsuch, meanwhile, suggested that "proselytizing" is just another word for "endorsement," which is impermissible under Lemon and seems to be what is happening when the government owns and maintains a 40-foot version of Christianity's central symbol on a highly conspicuous piece of public property.

"I don't see the daylight between proselytizing and endorsement," Gorsuch said. "It seems to me that you are taking us right back to the dog's breakfast you've warned us against." Chief Justice John Roberts agreed. "What you advertise is a pretty concise test," he said, "but it degenerates pretty quickly into, well, I need to know about this, I need to know about that, and becomes kind of a fact-specific test rather than the crisper one that you propose in your brief."

Justice Brett Kavanaugh noted that the four dissenters in Allegheny County v. ACLU, the 1989 case in which the Court said a nativity scene in a courthouse violated the Establishment Clause, all agreed that "the permanent erection of a large Latin cross on the roof of city hall" would be unconstitutional. "Because it constitutes proselytizing," Carvin said, "we certainly do agree." But if the government takes that cross, sticks it on a highway median, and calls it a memorial, it is no longer prohibited proselytizing, according to the American Legion. Katyal agrees that the cross in that context is constitutional—unless there's a statue of Jesus nailed to it.

Justice Elena Kagan, one of three Jews on the Court, pushed back against the argument that the Latin cross "has taken on a secular meaning associated with sacrifice or death or commemoration," as Acting Solicitor General Jeffrey Wall, who also urged the justices to declare the Bladensburg monument constitutional, put it. "It is the foremost symbol of Christianity, isn't it?" Kagan said. "It invokes the central theological claim of Christianity, that Jesus Christ, the Son of God, died on the cross for humanity's sins and that he rose from the dead. This is why Christians use crosses as a way to memorialize the dead. It is because it connects to that central theological belief."

But that does not mean every government-hosted memorial featuring a cross has to go, said Monica Miller, the lawyer representing the American Humanist Association and three local residents challenging the monument. The constitutionality of such displays, Miller said, depends on details such as the monument's purpose, history, location, size, and appearance. "It's very difficult, and I think that's why the Court hasn't come up with that one, you know, singular test, because the cases are complex," Miller said. "That's the Establishment Clause."

Several justices noted that the Court has failed to give judges clear guidance in this area. "If I were…a lower court judge and I get that type of analysis," Roberts observed, "I'm just going to throw my hands up."

Kavanaugh noted that the Supreme Court in recent decades has made little use of the Lemon test. "If the test isn't being used, that would suggest that the test doesn't work for this context," he said.

Gorsuch agreed. "It has resulted in a welter of confusion," he said. "Is it time for the Court to thank Lemon for its services and send it on its way?…I think a majority of this Court, though never at the same time, has advocated for Lemon's dismissal….What about all those poor court of appeals judges who are left still with confusion?" I will go out on a limb and predict that they will be no less confused after the Court reaches a decision in this case.

Addendum: Stanford law professor Michael McConnell, who filed a brief in this case on behalf of the Becket Fund, proposes an "historical approach" to the Establishment Clause that starts by asking what counted as "an establishment of religion" when the First Amendment was written. In that context, he says, displays like the Bladensburg cross would be constitutional, but unconstitutional practices would include, in addition to establishing an official church and coercing religious practice, "government action that favors one religion over another, that involves the government in doctrinal or ecclesiological issues, that invests religious bodies with political power, and much more." McConnell argues that "an historical approach is bounded and objectively administrable, but not as narrow as 'coercion' or as subjective as 'endorsement.'"