In a State of Emergency, the President Can Control Your Phone, Your TV, and Even Your Light Switches

Under a little-known regulation that dates back to the 1930s, the president has legal power over electronic transmissions.

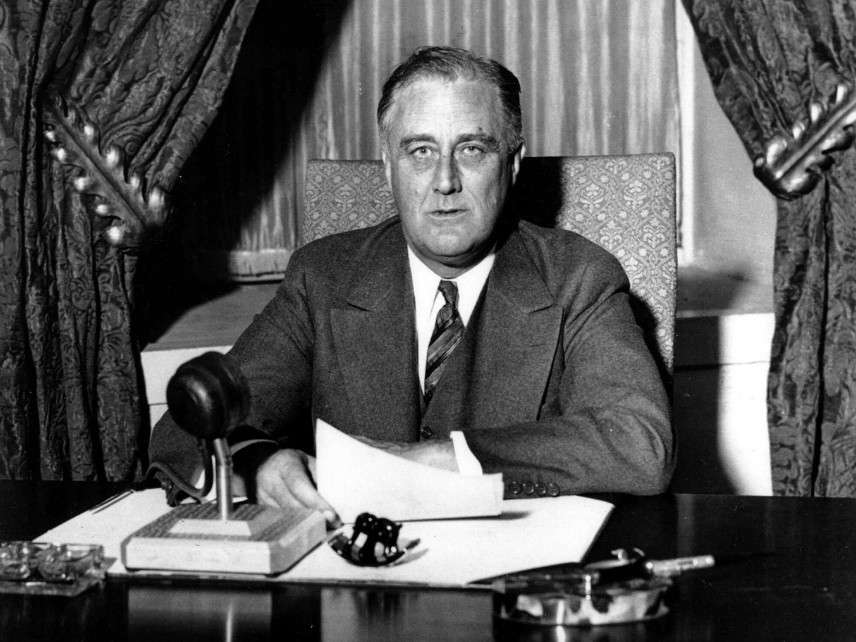

December 11, 1941, is not nearly as memorable a date as the one that lives in infamy. But that Thursday after Pearl Harbor is still an important moment in American history, because it's the day that Germany declared war on the United States and the U.S. immediately reciprocated. And it was on that date that President Franklin Roosevelt told his press secretary, Stephen T. Early, that the government should take over one of the national broadcast networks.

Early informed James L. Fly, the chairman of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and director of the newly created Defense Communications Board (DCB), that Roosevelt had personally directed Fly to acquire a national broadcast network for the government. The DCB had been created for just such a national emergency: Its mandate was to coordinate all communications (both military and civilian) in case of war or another national emergency. Both the FCC and the DCB were empowered by Section 606 of the 1934 Communications Act, which expressly gave the president full control over electronic transmissions in such circumstances.

Section 606(c), in particular, gave the president full control to suspend and commandeer the country's entire electronic regulatory system. "Upon proclamation by the President that there exists war or a threat of war, or a state of public peril or disaster or other national emergency, or in order to preserve the neutrality of the United States," the law said, the president "may suspend or amend, for such time as he may see fit, the rules and regulations applicable to any or all stations or devices capable of emitting electromagnetic radiations within the jurisdiction of the United States as prescribed by the Commission." He had the power to shut down any radio station—"or any device capable of emitting electromagnetic radiations between 10 kilocycles and 100,000 megacycles, which is suitable for use as a navigational aid beyond five miles"—and could commandeer its equipment, "upon just compensation to the owners."

Chairman Fly was prepared for this request, because he'd been working on broadcast propaganda plans for more than a year. Yet Fly was a civil libertarian, and he strongly disagreed with the White House's order. Pushing his own plan, he ultimately convinced his colleagues in the administration that propaganda delivered by Jack Benny, Bob Hope, and other established radio stars would be far more persuasive than any federal functionary offering exhortations on state-run broadcasts.

But the communication between Early and Fly on December 11, 1941, remains significant in the history of American media regulation. It's the closest we came to the implementation of Section 606 and a government takeover of America's electronic communications system. Section 606 remains in effect today, because the Telecommunications Act of 1996 incorporated substantial sections of the original 1934 Communications Act.

Now that President Donald Trump is declaring yet another national emergency, it's important to reconsider Section 606. Most Americans have no idea that these emergency declarations permit such sweeping powers over our way of life. Upon declaration of a national emergency, Trump can commandeer every single television and radio station in the United States and demand that it perform as he directs.

That's bad enough. But wait: There's more!

The law permits the White House to take over any device that emits radiofrequency transmissions. In 2019, that's everything from your implanted heart device to the blow dryer for your hair. It includes your electric exercise equipment, any smart device (such as a digital washing machine), and your laptop—basically everything in your house that has electricity running through it.

We tend to think of the FCC as the policeman of the airwaves: issuing licenses, fining stations for airing indecent words, and otherwise regulating radio and TV broadcasters. But its mandate is far broader. The FCC regulates all devices that can transmit electricity. Even the light switches in your home are regulated by the FCC, as they transmit tiny amounts of electricity in the course of operation. Though the danger to the public is minimal, the FCC regulates basically everything using electricity in your house.

Household electric devices usually fall into one of two lightly regulated categories: "incidental radiators" or "unintentional radiators." Your cell phone, the transmission tower of a radio station, and even your Bluetooth device are intended to radiate electricity, so they therefore fall into a more regulated category: "intentional radiators."

But when it comes to a president's emergency powers, these subcategories are essentially meaningless. The White House's sweeping power over electricity in a national emergency still exists, and it has been conferred upon the President by legislation passed by Congress. We're simply lucky that it's never been used previously, and that the only serious attempt to use Section 606 in U.S. history was stymied by a bureaucrat with a civil libertarian streak.

So remember: If he wants, President Trump—or any other president—can control your radio, your TV, your laptop, and even your light switches and microwave oven. Once again it's obvious: The history you don't know can hurt you.

Show Comments (146)