Did Vaping Stop the Downward Trend in Adolescent Smoking?

One survey shows cigarette use holding steady, while another shows it continuing to fall.

Survey results published this week indicate that cigarette smoking was about as common among high school students last year as it was in 2017. Is this evidence that the surge in adolescent vaping is finally reversing the decline in adolescent smoking that began in the late 1990s? Probably not.

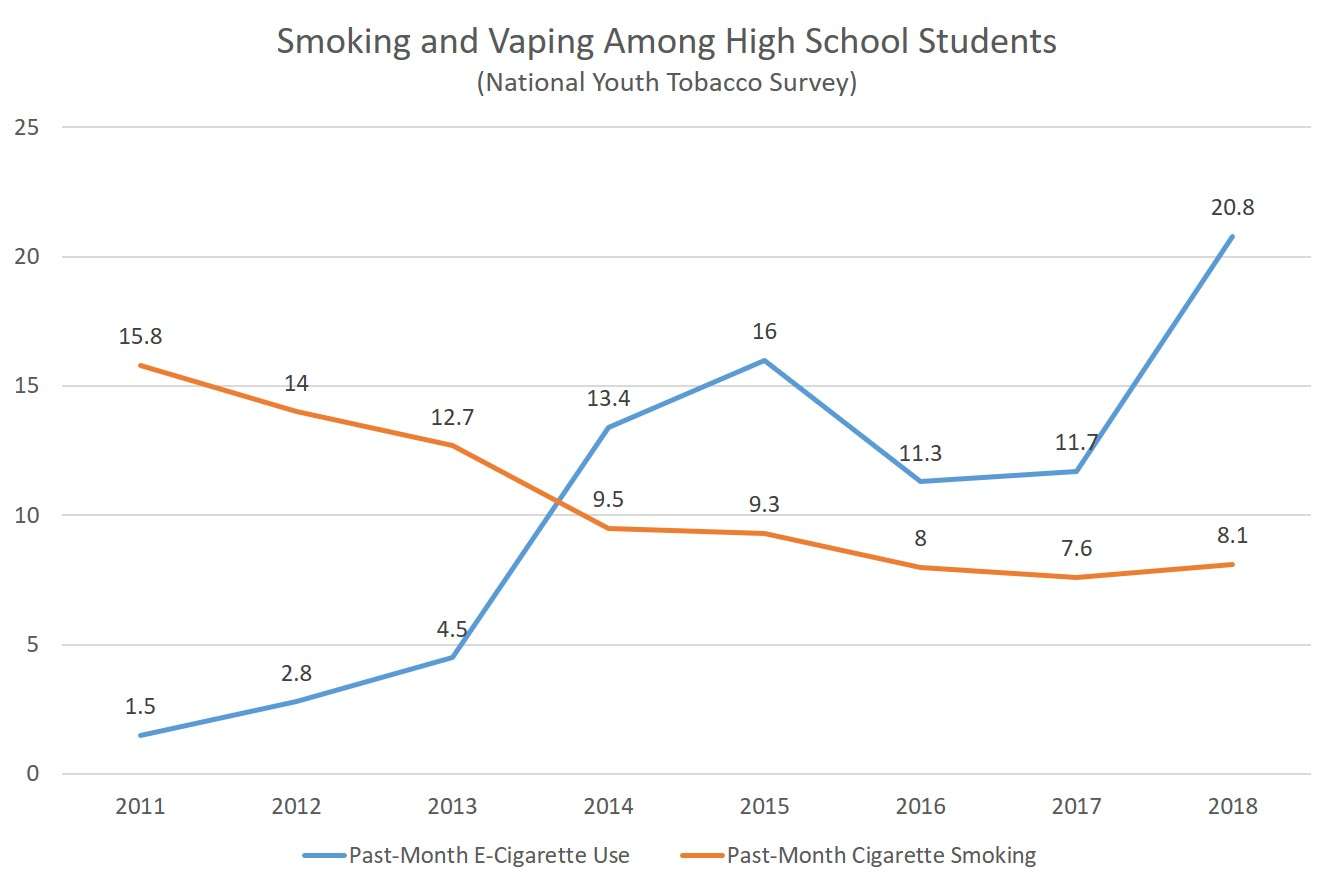

In the 2018 National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS), which is sponsored by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 8.1 percent of high school seniors reported smoking cigarettes in the previous month, compared to 7.6 percent in 2017. The difference was not statistically significant. Meanwhile, as the Food and Drug Administration revealed last fall, 20.8 percent of high school students reported past-month e-cigarette use in 2018, up from 11.7 percent in 2017.

"Cigarette smoking rates have stopped falling among U.S. kids," the Associated Press says, "and health officials believe youth vaping is responsible." A.P. quotes CDC spokesman Brian King, who says, "We were making progress, and now you have the introduction of a product that is heavily popular among youth that has completely erased that progress."

King is being tricky here. The "progress" has been "completely reversed" only if you count vaping, which does not involve tobacco or combustion, as a kind of "tobacco use" and ignore the huge difference in health hazards between the two forms of nicotine consumption. The CDC, notwithstanding its supposed focus on minimizing morbidity and mortality, habitually obscures these important distinctions. From a public health perspective, a situation in which 20 percent of high school students are vaping while 8 percent are smoking is vastly preferable to a situation in which 0 percent are vaping and 29 percent are smoking (as the NYTS found in 1999).

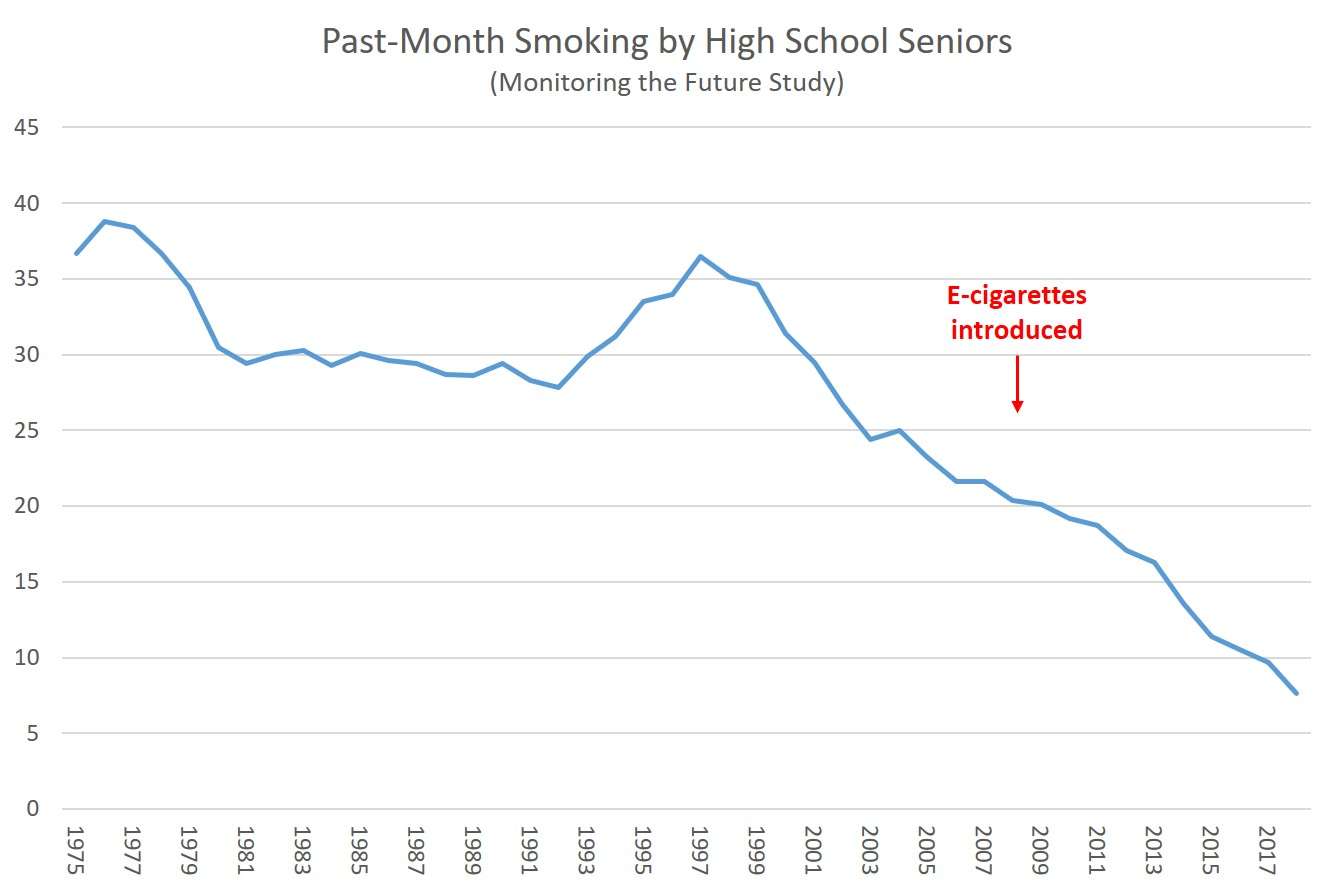

While the NYTS indicates that past-month cigarette smoking has been flat among high school students since 2016, another government-sponsored survey, the Montoring the Future Study, which also detected a big increase in vaping last year, shows a continuing decline in past-month smoking among 12th-graders:

Past-month cigarette smoking also continued to fall among 10th-graders in that survey, although it ticked upward among eighth-graders (from 1.9 percent in 2017 to 2.2 percent in 2018).

This week Food and Drug Commissioner Scott Gottlieb reiterated his determination to reverse the upward trend in adolescent vaping, even if that means making it harder for adult smokers to quit by switching to e-cigarettes. "As a society, we've made great strides in stigmatizing cigarette use among kids," he said. "The kids using e-cigarettes are children who rejected conventional cigarettes, but don't see the same stigma associated with the use of e-cigarettes. But now, having become exposed to nicotine through e-cigs, they will be more likely to smoke."

In other words, Gottlieb worries that vaping is leading to smoking by teenagers who otherwise never would have experimented with tobacco. But if that pattern is common, it's hard to explain why smoking has fallen to record lows among both teenagers and young adults in recent years, or why the downward trends accelerated as vaping became more popular. By contrast, the hypothesis that teenagers who otherwise would be smoking are instead vaping is consistent with the data we've seen so far.

Maybe Juul, the leading e-cigarette, changed everything by offering better nicotine delivery in a discreet and convenient device. But it is hard to fathom why someone who likes Juul and its imitators would be attracted to products that are not only dirtier, smellier, and much more hazardous but also more expensive. If Gottlieb is right, last year's 78 percent increase in vaping by teenagers should be followed by a substantial increase in smoking among teenagers and young adults within the next few years.

A.P. notes that some researchers "had linked e-cigarettes to an unusually large drop in teen smoking a few years ago, and they say it's not clear to what extent the decline in smoking has stalled or to what degree vaping is to blame." One those researchers, Georgetown's David Levy, warns that "it's not clear yet what's going on, and it's best to not jump to any conclusions."

Show Comments (23)