Term Limits for Supreme Court Justices Won't Save Us

But they might be worth trying anyway.

Debates over the merits of lifetime appointments for Supreme Court justices are literally older than the Supreme Court itself.

Alexander Hamilton tackled the question in Federalist 79, contrasting the lack of any limits on Supreme Court justices' tenure with the rules for judges in New York State, which at that time forbade anyone over age 60 from serving on the bench. Hamilton ultimately dismissed worries about judges becoming unable to discharge their duties in advanced age—"The deliberating and comparing faculties generally preserve their strength much beyond that period in men who survive it"—and concluded that those worried about a "superannuated bench" have an "imaginary fear."

More than two centuries later, there is still no limit on how long Supreme Court justices may serve. That makes the Court an outlier not just among global democracies but within the United States. Most states have mandatory retirement ages for judges (usually at age 70 or 75), and some require sitting judges to face the voters at predetermined intervals for up-or-down retention elections.

Many of the arguments in favor of placing limits on judges' tenure are the same as they were in Hamilton's day: concerns about the mental fortitude of elderly jurists, or of a Supreme Court that grows out of touch with the nation whose laws it reviews. Unlike in Hamilton's time, though, it is hardly uncommon for judges to remain on the bench well past age 60. Indeed, the average age of the eight current Supreme Court justices is over 67 years. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, who is 85, says she wants to remain on the court until she is 90.

But the acrimonious fight over whether Judge Brett Kavanaugh should be given one of those lifetime appointments has introduced a new angle to this age-old debate. Term limits "would make the current system fairer—and tone down the intensity of the confirmation process," David Leonhardt opined in the The New York Times last month. It would also impart other benefits, he added: removing aging judges from the high court, for example, and giving the Senate a predicable schedule for handling its advice-and-consent duties.

Since we're facing the prospect of a Supreme Court with a solidly conservative majority for the foreseeable future, it's probably not surprising that term limits are generating new interest on the left. Ezra Klein has already drawn a link between Kavanaugh's contentious confirmation process and reality of a lifetime appointment. His Vox colleague Lee Drutman has been more explicit, writing in June that "it's time for term limits for Supreme Court justices."

"If justices were staggered in their terms, everyone in Washington would know they'd have another opportunity to change the Court again soon enough," he wrote. "This regularity could also move toward more of a norm of fair play."

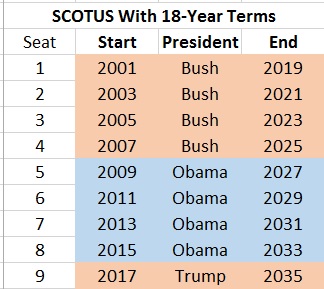

The most well-formed plan for term limits comes from Fix The Court, a nonpartisan group interested in making the Supreme Court more open and accountable. (They also favor TV coverage of oral arguments and making judges file annual financial disclosures.) Fix The Court favors fixed 18-year terms, allowing every president to nominate a justice in the first and third year of each term.

If 18-year term limits had been imposed in the past, the current makeup of the Supreme Court would change only slightly. Right now there are four justices nominated by Democratic presidents and four (soon to be five) nominated by Republicans. Using Fix The Court's system, the current court would have a 5–4 Republican slant, with President Donald Trump getting ready to replace one of President George W. Bush's picks next year.

This arrangement, the group says, would solve "key problems with the court that have led to the extreme partisanship and harmful polarization we see today."

This appeal to civility is one that might find a receptive audience after the rancorous Kavanaugh hearings. Would term limits (or age limits), and the predictability they provide to the presidents and senators responsible for choosing and confirming Supreme Court justices, save us?

Probably not. Would the stakes really be that much lower if Kavanaugh were in the running for an 18-year term on the court? With everything else being equal—in other words, with the current conservative-liberal split and the potential fate of abortion law hanging on the outcome—the promise that Kavanaugh would merely sit on the bench until 2036 would probably not bring Democrats down from the barricades, nor would it make Republicans any less likely to push for his confirmation.

Orin Kerr, a law professor at USC Gould and a contributor to the Volokh Conspiracy blog (which Reason publishes), is similarly skeptical—though as we'll see, he favors term limits for other reasons. "It would still be one politician doing the nominating and 100 politicians doing the advising and consenting," he says. "It's an inherently political process."

The politicization of the Supreme Court is worrying, but fixing it is a larger project than merely setting fixed terms for justices. As Sen. Ben Sasse (R–Neb.) observed during the early stages of the Kavanaugh confirmation process, the heightened role of the Supreme Court has as much to do with the failings of the other branches of government as it does with anything inherent to the court itself.

"When we don't do a lot of big actual political debating here, we transfer it to the Supreme Court, and that's why the Supreme Court is increasingly a substitute political battleground in America," said Sasse. "It is not healthy."

Even if judicial term limits aren't a bulwark against a hyper-partisan environment that's increasingly spilling over into the Supreme Court, the idea is worth considering for other reasons.

For one, people seem to like it. A Morning Consult/Politico poll conducted in July—just after Justice Anthony Kennedy announced his retirement—found that 61 percent of voters favored term limits for Supreme Court justices, including majorities of Democrats, Republicans, and independents.

For another, it would openly acknowledge something everyone already knows: that control of the Supreme Court is a reward for electoral success.

The Founders intended lifetime Supreme Court appointments to buffer the justices from political interests, but it's clear now—if it wasn't already when Republicans held a vacant seat on the court open for the final year of President Barack Obama's term—that both sides view Supreme Court appointments as the spoils that come from controlling other branches of government.

If the high court is going to be politicized anyway, it makes sense to have those seats be democratically accountable.

"If the Supreme Court is going to have an ideological direction—which, for better or worse, history suggests it will—it is better to have that direction hinge on a more democratically accountable basis than the health of one or two octogenarians," says Kerr.

Imposing term limits would require a constitutional amendment, which may be an impossibly heavy lift. It's also not clear how the transition would work: Which current justice gets the boot first? And it's not difficult to envision stumbling blocks once the system was up and running. Fix The Court's proposal would have presidents nominating judges in the first and third years of each term, but there's no mechanism to stop, say, a Republican-controlled Senate from refusing to have a vote on a Democratic president's third-year nominee and holding the seat open.

There would be unintended consequences too. Knowing that the winner of a presidential election will get two Supreme Court nominees could change the behavior of voters and candidates, possibly making presidential contests even higher-stakes affairs than they are now, when winning carries only the possibility of influencing the makeup of the court.

In all likelihood, nothing will change. We will continue to muddle through with the same broken process. Term limits, or the lack thereof, will not fix the underlying problems plaguing all aspects of the Kavanaugh confirmation process.

It may be that the questions about how long a judge should serve are as impossible to answer today as they were in 1788 when Hamilton was writing about them.

"The result, except in the case of insanity," he concluded in Federalist 79, "must for the most part be arbitrary."

Show Comments (73)