John Mackey and Conscious Capitalism Have Won the Battle of Ideas With Everyone but Libertarians

Why can't free marketers celebrate entrepreneurs and titans of industry who change our world unless they admit they're in it only for the money?

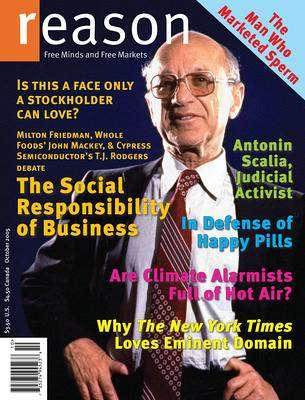

Thirteen years ago in the pages of Reason, John Mackey, co-founder and CEO of Whole Foods Market, debated Milton Friedman, the Nobel-winning economist famous for declaring that "the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits," and T.J. Rodgers, the CEO of Cypress Semiconductor who was (rightly!) famous for publicly telling buttinsky activist-investor nuns that they had no understanding of how to create jobs (the Catholic schoolboy in me still thanks Rodgers every night during my evening prayers).

Mackey argued an early version of a business philosophy that he would later codify in a 2013 book, Conscious Capitalism, and a nonprofit organization of the same name. Contrary to Freidman's Ahab-like focus on shareholder value, Mackey said,

The enlightened corporation should try to create value for all of its constituencies. From an investor's perspective, the purpose of the business is to maximize profits. But that's not the purpose for other stakeholders—for customers, employees, suppliers, and the community. Each of those groups will define the purpose of the business in terms of its own needs and desires, and each perspective is valid and legitimate.

Friedman and Rodgers toed the standard libertarian line: Take care of profits and shareholders, and good things will follow. Markets are set up in such a way that profits happen only when what a business does is valuable and wanted; the business can keep making money only if it uses resources wisely and efficiently, which includes paying good wages to keep talented people around. The intricate interplay of investors, entrepreneurs, employees, raw materials, competition, and so forth guarantees that if a company is doing right by its financial backers, it will be doing right by its workers, customers, and society.

According to this view, any discussion of the "social responsibility of business" to do anything other than earn a buck (such as Whole Foods' support of charities picked by local store workers) is either cheap P.R. or a dangerous invitation to all sorts of new expectations and regulations layered on top of the already brutally hard business of keeping the lights on at your store, factory, or hot dog stand. (As Joseph Schumpeter noted in his 1942 book Democracy, Capitalism, and Socialism, in any given year more businesses go tits up than make a profit.) "Mackey's philosophy demeans me as an egocentric child because I have refused on moral grounds to embrace the philosophies of collectivism and altruism that have caused so much human misery, however tempting the sales pitch for them sounds," Rodgers complained, even as Mackey insisted that "my argument should not be mistaken for a hostility to profit."

Today that 2005 debate reads like it's from the distant past, if not from a different planet. Friedman is dead, of course, and Rodgers retired in 2016 after helming Cypress for 34 years. Whole Foods is now part of Amazon and, more important, helped to transform the stodgy, old grocery business so fundamentally that my local Kroger store in Oxford, Ohio, has two Asian guys making sushi in plain sight eight hours a day and enough organic produce on every shelf that the local food co-op, a fixture in college towns, is barely scraping by. Walmart is not simply the largest seller of guns and ammo in America; it moves more organic produce than anybody else.

And here's the thing: Mackey's call for businesses to explicitly care about more than revenue per square foot or investors' earnings has effectively won the argument with just about everyone but libertarians.

"In the last 13 years, more and more people are beginning to see it our way," Mackey told me in a just-released podcast that was recorded last month at FreedomFest, the annual gathering of 2,000 libertarians in Las Vegas. "Honestly, I get the biggest pushback when I come to FreedomFest. I'd say the hardcore libertarians don't believe it, though people who run businesses tend to believe it….The enemies of business and the enemies of capitalism have put capitalism and business in a very narrow box, where it's all about greed, it's all about selfishness, it's all about just money, money, money…..There's a deep cynicism out there about business and businessmen, and economists fall into the trap. They say, 'Yeah, it is all about money. Get over it!' But I've known lots of entrepreneurs in my life—hundreds of them—and very few of them started their businesses simply to make money. They had some kind of dream or vision they wanted to realize."

It's not that America's business class has been magically transformed from uptight, Robert McNamara types in towering corporate skyscrapers or cigar-chomping, baby-stomping, tuxedo-wearing pigs into turtleneck-clad hippies who use organic deodorant or everyday-is-casual-Friday-clad hipsters riding penny-farthings to work. But there's no question that the firms and start-ups that define the cutting edge of contemporary capitalism—everything from Apple to Chipotle to WeWork—grok a Whole Foods vibe much more than they do, say, the ethos of General Electric, which was just dropped from the Dow Jones Industrial Average after a 100-year run.

People want to work for companies that not only have social commitments but live them every day in the office or store. Many customers willingly pay a premium by patronizing companies that express similar values or employ practices that accord with various environmental, philosophical, or social views. These companies (the successful ones, anyway) don't use such commitments as an excuse to deliver shitty service or products. It's more of a giveaway, like the toy in a McDonald's Happy Meal. And they face real wrath when they contravene their own stated commitments. Chipotle, which prided itself on using local organic ingredients and being transparent about its operations, is still struggling with fallout from a 2016 e. coli outbreak. People aren't just scared to eat there; they feel betrayed. In 1993, the fast-food chain Jack in the Box served food that killed four and injured 178 others. Its rehabilitation was simply about making customers feel safe to eat there, which is an easier lift.

As we move further into a post-scarcity economy, one in which our basic material needs are completely taken care of, we move into a world where our choices will be guided by more than simple questions of cost, availability, or even quality. Consumption has always been a symbolic activity as well as a starkly pragmatic one. Take it from a long-dead economist whom we can safely assume never wore sandals to work or called for team building via goat yoga or paintball outings:

"Choosing determines all human action," wrote the eminent Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises more than 50 years ago, sounding more like Jean-Paul Sartre than Adam Smith. "In making his choice, man chooses not only between various materials and services. All human values are offered for option. All ends and all means, both material and ideal issues, the sublime and the base, the noble and the ignoble, are ranged in a single row and subjected to a decision which picks out one thing and sets aside another."

In a world where supermarket shelves are crammed with endless choices, commerce is about speaking to consumers' moral and ethical values every bit as much as their plummeting blood-sugar levels. The same goes for workers: Given a choice between working for a company that offers a compelling, holistic vision of the world that aligns with your own and one that doesn't, which are you more likely to sign up with?

This needn't be a totalizing vision, in which everything we do every minute of every day must have deep ethical and spiritual meaning. Many of us may want to fully separate work from play or personal life. But as work becomes more artisanal and expressive (even cake baking is now seen as akin to painting the Mona Lisa), it seems likely that the fusion of work and personal values will be increasingly taken for granted. You can call it virtue signaling, but since when is signaling a shameful activity, especially among free-market libertarians, anarchists, and fellow travelers? All things being equal (or even just most things being equal), why wouldn't you want to work and shop at places that share your values?

Libertarians who reflexively recoil from ideas like conscious capitalism seem to do so mostly because they think it's an attempt to get with the cool kids on the left or because they view it as a betrayal of foundational values, insights, and axioms developed by Friedman and others under very different circumstances. Friedman made his original statement about corporate social responsibility in 1970, at a time when belief in what John Kenneth Galbraith called "the new industrial state" was at its zenith. Through a mix of market power and cronyism, massive corporations such as IBM, Xerox, Philip Morris, and GM had supposedly tamed the vicissitudes of the marketplace. They were immune from the ups and downs of smaller, less-efficient, poorly managed firms. These companies would exist forever and would provide cradle-to-grave employment, health care, and retirement for us all, taking over many basic functions of government.

Friedman recognized how wrong that consensus was: The great mid-century monopolists of the U.S. economy were already falling apart due to mismanagement, growing global competition, and failure to adapt and innovate. He understandably bridled at the idea that businesses should be concerned with more than their bottom line. They were about to go out of business, and here they were, talking about all sorts of things completely unrelated to profit. Politicians and activists had their hands in the supposedly bottomless pockets of America's leading corporate citizens.

But nearly 50 years later, we live in a very different world. Despite all sorts of ups and downs and a global recession, we are infinitely wealthier and better off. We live in a world of super-abundance that is provided not by governments but by endlessly churning, innovative businesses that change the world and then die off or limp along as zombie versions of their formerly great selves, barely remembered even by their biggest fans. There is just one Blockbuster video store left only a couple of decades after the chain changed all our viewing habits. Anyone remember just how great BlackBerry's phones were?

If the idea that where you buy and work should reflect your core values is ascendant, there's still a much tougher task for Mackey and his nonprofit, Conscious Capitalism. In the podcast, I also talked with Alexander McCobin, the CEO of Conscious Capitalism (and the founder of Students for Liberty). The group hopes to pull together companies and startups that share the vision that businesses should care about more than shareholder value. One goal is create a vibrant community that can share experiences and promote best practices, especially for novice entrepreneurs. Another goal is to change the way the world thinks about business.

"We don't want to just help the businesses out" by sharing advice and building networks, says McCobin. "We want to make sure we're sharing their stories with the world to change the narrative about business and society. We want to highlight all these businesses and business leaders who are making the world a better place, why business is a force for good, and to encourage people to go into business to make the world a better place."

The idea that businesses make the world a better place is a point on which virtually all libertarians wholeheartedly agree. It's common to hear libertarians say that Bill Gates (or Ted Turner, John D. Rockefeller, Henry Ford, etc.) did far more for humanity during his days as a rapacious, profit-driven businessman than he has done as a philanthropist. Isn't creating cheap, ubiquitous, good-enough software or driving the price of home heating oil down to nearly zero worth more than free money for libraries?

That way of thinking reflects a disconnect that libertarians should engage with and work to resolve within our movement. We aspire to create a world in which individuals are free to pursue happiness in whatever peaceful way they want. We recognize that commerce and work, every bit as much as art, music, and writing, are expressive. Yet we can't quite celebrate entrepreneurs and titans of industry who change our world unless they admit they're in it only for the money.

Here's the full podcast with Mackey and McCobin. Go here to subscribe via RSS, iTunes, and more.

Show Comments (200)