All Over the World, People Love Bootleg Moonshine and Hate Taxes

If you don't want a black market in booze to develop, keep the tax man on a leash and regulators in check.

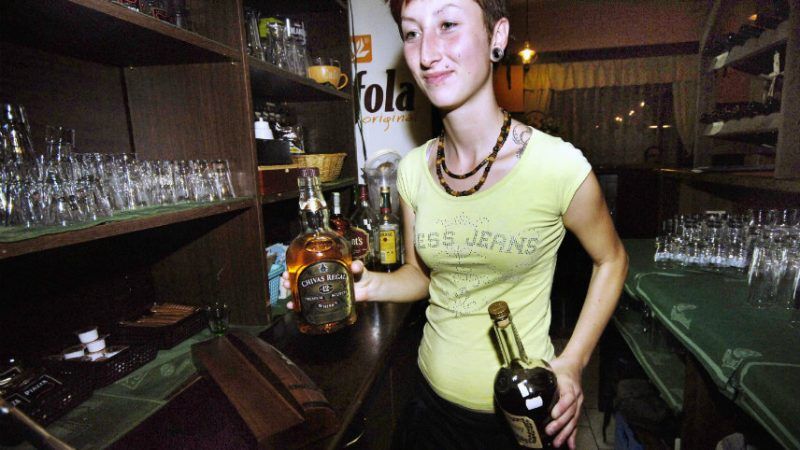

One enduring image of Prohibition is that of people sipping bathtub gin—illegal booze of dubious quality and safety, cooked up to satisfy the thirst of drinkers in an America that tried to ban alcoholic beverages. Bathtub gin was the result of regulators trying to eliminate access to a popular product—inevitably inviting supply to meet demand in the black market.

But you don't need an outright ban on alcohol to fuel the production of bathtub gin and its equivalents. A new report shows that the same result has been achieved in many countries through the imposition of excessively high taxes and overly restrictive regulations.

"Illicit alcohol accounts for a sizeable proportion of total alcohol, particularly in low- and middle-income countries," notes a new report (PDF) from the International Alliance for Responsible Drinking (IARD), a non-profit organization supported by the alcoholic beverage industry. The report cites World Health Organization (WHO) research, published in 2014 (PDF), to the effect that "illicit and informally produced alcohol accounts for nearly a quarter of the alcohol consumed globally."

More specifically, the IARD breaks the numbers down by country: In the Czech Republic, for example, an estimated 7 percent of booze is illicit, overshadowed by the 28 percent of alcoholic beverages that are illegally produced in Brazil, the 34 percent in Mexico, and the whopping 66 percent in Mozambique.

What's the attraction of drinking the local equivalent of bathtub gin when commercially produced products are widely available?

"Unrecorded alcoholic beverages are generally less costly than recorded alcohol," WHO dryly acknowledged in 2014. The IARD report goes into a bit more detail as to why that might be, noting that "these beverages are untaxed and outside of regulated production that can increase cost," which means there "is often a significant price difference between illicit and legitimate products, driving demand."

Availability drives demand for black market booze, too—especially when officialdom goes out of its way to make the legal stuff hard to get.

"Disproportionate regulation of the availability of legal and branded products, such as severe restrictions around licensing hours or on outlets, also drives the consumption of illicit alcohol, which is easily available from unregulated and informal sources," the IARD reports.

That makes a lot of sense when you consider that Prohibition represented the ultimate example of "severe restrictions around licensing hours or on outlets." Its near-total ban on commercial production and sale of alcoholic beverages did a legendarily bang-up job of driving consumers to "unregulated and informal sources." Some countries, or jurisdictions within countries, continue to impose total bans on alcohol consumption comparable to Prohibition, making the black market the only place to get a drink. Lesser restrictions also result in off-the-books production and distribution to whatever extent is needed to meet demand.

"In Latvia," the IARD reports, 40 percent "of unrecorded alcohol drinkers said that they consume contraband alcohol because there are fewer restrictions on hours and days of sale."

Turning to illegal sources becomes especially attractive, the IARD report says, in cultures that have a tradition of home and artisanal production and sale of alcoholic beverages. That's particularly true because "[m]any of these beverages are of high quality and comparable to regulated beverages" (though many others are not so good or safe, comparable to the American experience with varying quality during Prohibition).

From shebeens—informal bars—serving homebrew across much of Africa, to home production of cachaça in Brazil and rice wine in Vietnam, people across much of the planet have the knowledge to make their own alcoholic drinks and a history of thinking that's a perfectly fine occupation. Why wouldn't they put those skills to use when it becomes desirable—and profitable—to do so?

So, if high taxes and restrictive regulations have been complicit in driving people to seek cheap and convenient booze on the black market, and the learning curve to do so is less than daunting, that would seem to bode failure for the WHO's preferred policy of hiking the price of alcohol through taxes and minimum prices and choking off availability by tightening regulatory screws. WHO officials may cite studies finding "raising the price of alcohol to be effective in reducing harmful use of alcohol," but the tax hikes and restrictions they propose apply only to the legal stuff and look like gifts to underground producers and distributors.

The IARD isn't immune to the siren song of control either, proposing increased monitoring and tracking of raw materials used in the production of alcohol (good luck with that; pretty much anything will ferment when given the opportunity). It also proposes various varieties of stepped-up enforcement and control, as if that's a new idea to the average bureaucrat.

More sensibly, the IARD recommends legalizing home production, promoting standards for production, and encouraging competitions to improve quality. It favorably mentions codes of conduct developed by shebeens and community organizations in South Africa. The industry group even suggests "appropriate pricing policies" and "favorable fiscal incentives" that could be interpreted as a suggestion to keep the appetite for taxes somewhat in check so as not to drive legal booze out of the market.

But let's not be coy. If you don't want a black market in booze to develop, keep the tax man on a leash and regulators in check. And then, maybe, you can avoid repeated iterations of Prohibition and the bathtub gin it made so famous.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Even the Chinese understand this. "The opioid problem is due to demand in America."

Specific product doesn't matter ? if it's in demand, reducing the supply will raise the price and eventually (sometimes almost instantly) lead to black markets.

Abolitionists tend to have a hard time comprehending this point.

I am making $150 reliably by tackling the web at home. A month earlier I have gotten $19723 from this activity. This development is staggeringly astonishing and its customary compensation for me is superior to anything my past office work. This activity is for all and everyone can without a considerable measure of a broaden join this correct currently by utilize this link... https://howtoearn.club

Not "illegal" (as far as I know, and I don't believe so), but some of my Croatian relatives by marriage prefer to drink wine that comes from their own small vineyards, because it's traditional and fun, as well as because it's economical. Without discounting any of them, it's not *only* cost, hassle, and raised hackles that count -- it's also the plain old positives of making your own.

Every generation in my family since Prohibition has made alcohol in some form, The easiest way is to buy apple cider and an unwaxed apple. Put some apple peelings into the cider and leave the cap loose so it can ferment. My grandmother used "hardening cider" to start wine, and used a pierced balloon as a fermentation lock, and added sugar to it every week until the balloon didn't stand up any longer.

My grandfather and his father made and sold corn liquor and applejack brandy.

I keep bees and make sack mead.

Put some apple peelings into the cider and leave the cap loose so it can ferment.

My college roommates did this my freshman year of college. There was a non alcohol policy in the dorms, and the bottle was sitting out in plain view, but the RA never said anything. Not sure if it was because he didn't care or if he didn't realize what we were doing. Felt kind of good to get away with something right under their noses though.

It's sort of funny how prohibitionist types never seem to connect their idea's regarding sin taxes to any other kind of taxes. If it's a tax on something 'sinful' the tax becomes magical and only then does it have effects on a market.

A Romanian coworker brought me an iced tea bottle filled up with the homemade hooch they make make there. Forget what they call it but made from plums I think.

Dayum. That stuff had more kick than an angry mule.

Interesting. An organization called the International Alliance for Responsible Drinking (IARD), a non-profit organization supported by the alcoholic beverage industry, is concerned about "illegal" (read: homemade) booze.

Hmm. Something tells me that they are concerned about something other than lost tax revenue or product quality.

All over the world, politicians, bureaucrats, and other busybodies pretend to care about their fellow human beings.