Gerrymandering Is Out of Control

Computers could be the key to resolving partisan fights over congressional boundaries.

For weeks this winter, Pennsylvania flirted with a full-blown constitutional crisis.

In January, the Democrat-controlled state Supreme Court sided with activists from the League of Women Voters and ordered state legislators to redraw the state's congressional district map. GOP lawmakers, who had created the boundaries in 2011 during the once-per-decade reapportionment process, had engaged in a heavy dose of gerrymandering—the practice of drawing district lines intentionally to favor one party over another. Not surprisingly, Republicans objected to the court order, even threatening to impeach some of the state high court's justices. The two branches of government appeared to be deadlocked, with each determined to check what it saw as partisan opportunism on the part of the other.

Republican lawmakers in the General Assembly blinked first, offering a new set of district lines on February 9. It was promptly rejected by Gov. Tom Wolf, a Democrat. A week later, the state Supreme Court produced its own map, drawn by Stanford Law School's Nathaniel Persily. Republicans howled that the court had unconstitutionally usurped a legislative power and asked the U.S. Supreme Court to intervene.

For now, uncertainty reigns.

Even when the crisis in Pennsylvania is eventually resolved, deeper issues regarding electoral district lines are likely to persist. Around the country, courts and independent redistricting commissions have been called upon. But so far, the big questions that haunt every such dispute—What makes a district gerrymandered? How do you draw a truly neutral map?—have proven surprisingly difficult to answer.

At least, that is, by human beings.

Some researchers, armed with powerful new electoral data, have begun asking what might happen if human decisions were entirely removed from the equation. If regular citizens, state lawmakers, and Supreme Court justices can't figure out redistricting, perhaps an algorithm can.

Anatomy of a Crisis

The roots of Pennsylvania's crisis lie in the 2010 midterm election. After winning huge electoral victories, Republicans set about the regularly scheduled task of redrawing the commonwealth's congressional district lines. In a state with about 1 million more registered Democrats than registered Republicans, it's not easy to carve out districts that virtually ensure GOP victories. But they managed it.

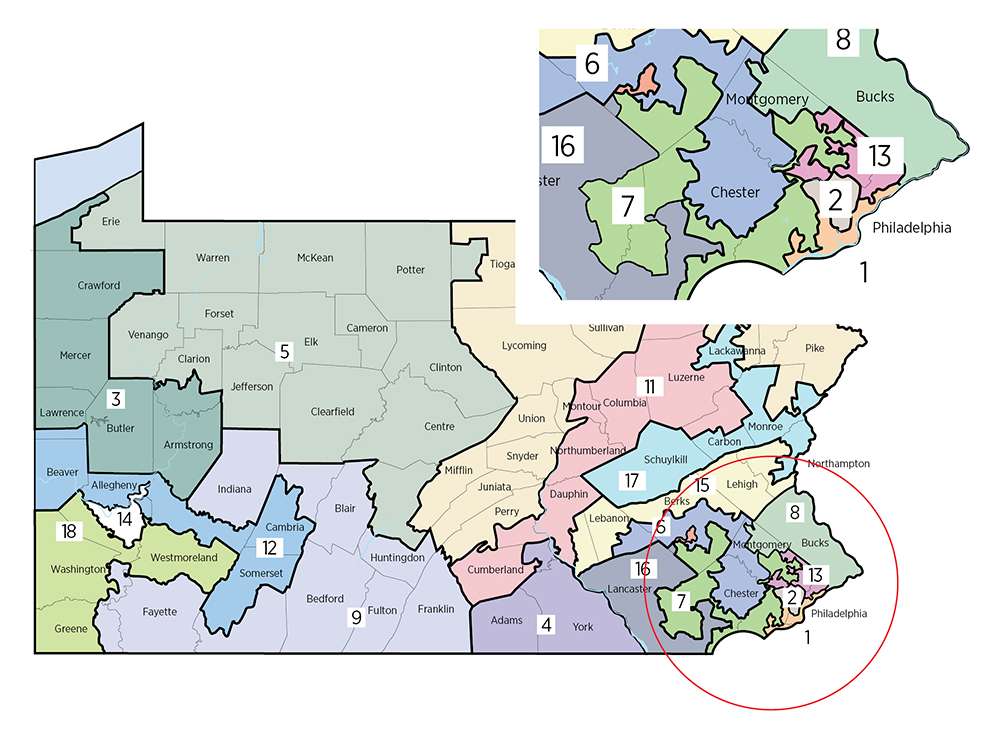

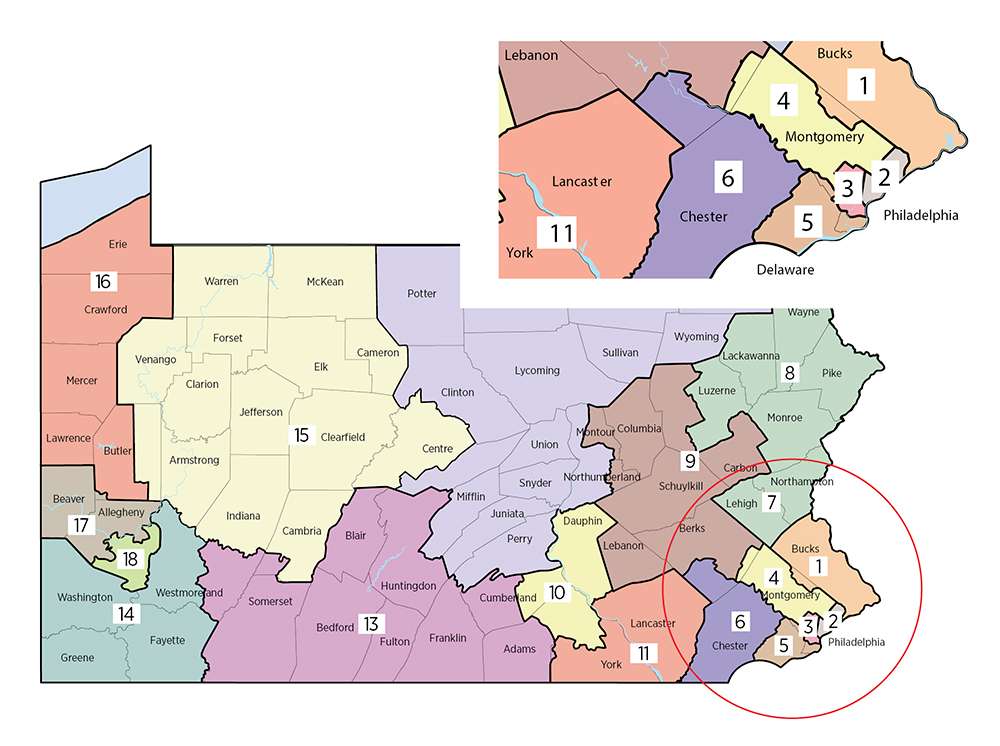

In 2012, thanks to the new maps, Republicans won 13 out of 18 races—even though Democratic candidates received more total votes. The 13–5 split in the state's congressional delegation persisted in the 2014 and 2016 elections, and the GOP-drawn districts made a Democratic takeover in 2018 seem nearly impossible to imagine.

Then in January, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ruled that the districts were "plainly, clearly, and palpably" unconstitutional because counties were unfairly fractured to give Republicans an advantage. In a 5–2 decision, the Court ordered the old maps scrapped. It then instructed the state legislature to draw new ones in less than a month. If lawmakers failed to do so on time, the Court said, the justices would do it themselves.

Pennsylvania Republicans accused the state Supreme Court of judicial imprudence. Although Pennsylvania judges are technically nonpartisan, they noted that all five justices who voted against the GOP's map had been elected as Democrats. One of them, Justice David Wecht, was elected in 2015, and had called gerrymandering "an absolute abomination" during his campaign. Republicans called that an implicit promise to strike down the 2011-era maps.

Wecht's comments, the party-line ruling in the League of Women Voters case, and the state Supreme Court's declaration that it had the authority to redraw the map without legislative input—a pretty clear violation of the rules found in both the state and the federal constitutions—looked to GOP lawmakers like a political coup from the bench. A bill to impeach several of the justices was introduced in the General Assembly, and all hell broke loose.

Amid the grumbling and the threats against sitting judges, GOP lawmakers did indeed draw a new map and passed it through both chambers of the legislature. Although it removed some of the most egregious elements of the old map, several analysts condemned it for maintaining a Republican tilt. "A prettier map can still conceal ill-intent," said Sam Wang, a neuroscientist who runs the Princeton Election Consortium site.

After Wolf vetoed the new districts, Speaker of the House Mike Turzai (R–Allegheny) and Senate President Joe Scarnati (R–Jefferson) wrote a joint letter accusing him of setting forth a "nonsensical approach to governance." Among other things, the governor had taken issue with the placement of Erie in a primarily rural district. But Erie is located in the state's sparsely populated northwest corner, near no other population centers. Where else, the GOP leaders asked, were they supposed to put it, given that "there are no voters in Lake Erie, and we are not allowed to go into Ohio, New York, or Toronto"? According to Turzai and Scarnati, the Democratic governor and Democrats on the state Supreme Court were conspiring to "divest the General Assembly of its constitutional authority to enact congressional districts."

If that was the justices' intent, they accomplished the mission on February 19 by releasing their own congressional district map and ordering the Department of State to use it for the upcoming midterm elections.

At first glance, the Supreme Court's districts appear less gerrymandered than either the 2011 map or the proposed Republican replacement. But a prettier map can still conceal ill-intent, and observers say Democrats stand to gain.

"This is the PA map Dems wanted," tweeted Dave Wasserman, the U.S. House editor for The Cook Political Report. "The PA Supreme Court's map doesn't just undo the GOP's gerrymander. It goes further, actively helping Dems compensate for their natural geographic disadvantage in PA."

Democrats could win between eight and 11 seats with the new map, Wasserman said. Other analyses came to similar conclusions, with Democrats favored in at least seven districts and having a good chance to win 10 or more—a big change from the previous 13–5 GOP edge.

Pennsylvania Republicans have petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court, asking the justices in Washington to rule that their state-level counterparts are usurping a power explicitly given to legislators in Article I, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution.* "Pennsylvania will be the future in every state if the Justices decide that judges should be redistricting kings," warned a Wall Street Journal editorial. Even President Donald Trump waded into the controversy. "Your original [map] was correct!" he tweeted. "Don't let the Dems take elections away from you so that they can raise taxes & waste money!"

'Destructive to Representative Democracy'

Pennsylvania faced the most acute gerrymandering crisis of the decade. But it is not the only place where an egregiously partisan map has been drawn. In 2011, North Carolina was carefully redistricted to give Republicans a significant electoral advantage. (A year later, the GOP won 10 of the state's 13 districts despite losing the aggregate vote.) The U.S. Supreme Court is currently weighing a challenge to Wisconsin's Republican-drawn districts, which critics say disenfranchise minorities in Milwaukee and other cities.

Democrats have increasingly seized on redistricting as an explanation for their electoral shortcomings. Gerrymandering is "destructive to the representative democracy that our founders envisioned," former Attorney General Eric Holder wrote in The Washington Post last year. He's now heading a campaign organization aimed at helping Democrats retake state legislative seats before the 2021 reapportionment happens.

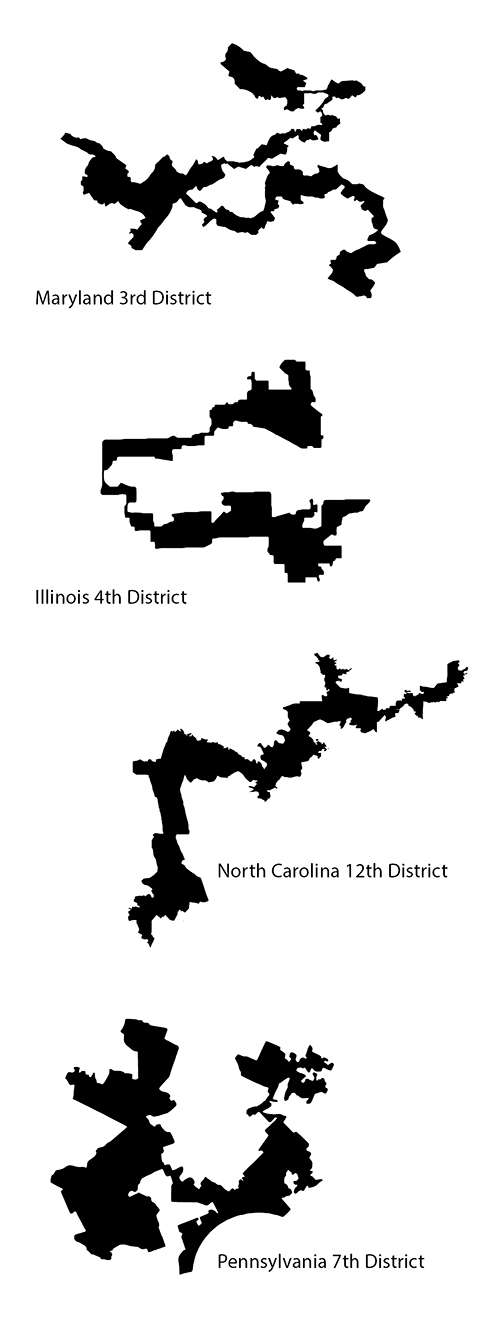

But Democrats have drawn maps designed to confer partisan advantage as well. In Illinois, the 4th district looks like a pair of earphones; its two halves are connected at one point by a strip only as wide as Interstate 294. Maryland's 3rd district bobs and weaves its way from Annapolis to Baltimore on a snaking path that in some places is no more than a few hundred yards wide.

Gerrymandering has been blamed for a lack of competitive congressional elections, for growing levels of extremism in both major parties, and for a perceived breakdown in trust between citizens and government. Opponents say it allows elected officials to choose their voters, rather than the other way around.

The practice is not singularly responsible for any of the ills attributed to it, and Democratic efforts to highlight the importance of fair districts are also fueled by partisan motivations. Yet as the showdown in Pennsylvania proves, battles over redistricting have the potential to become true constitutional crises.

Of Packing and Cracking

Fights over the "best" way to set district boundaries can seem like petty partisan distractions—just another way in which America's two major parties insulate themselves from meaningful competition in the political market.

But there's more to redistricting than simple partisan jockeying, says Walter Olson, a senior fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute. Redistricting also offers a glimpse into the hidden ways in which politicians exert and preserve their power.

"You miss a lot of it if you look just at the Republican vs. Democratic stuff," says Olson, who sat on a commission** that proposed alternative redistricting methods for Maryland in 2015.

That experience gave Olson a new perspective on how redistricting manipulates the political fortunes of individual politicians and shapes the membership of Congress. District lines are sometimes drawn for intensely personal reasons—to remove a prospective challenger from an incumbent's turf, for example, or to put two opposition lawmakers in the same district so that only one can win the seat.

"A lot of it is the ability of leadership to punish backbenchers. A lot of it is the alteration of districts in a way that benefits people with access to inside political resources," Olson says. "I realized that the system allowed manipulation of a much more varied and subtle type than I'd expected."

None of this is new. The word gerrymandering was coined in the 1810s to describe a particularly lizardy-looking district carved out of rural Massachusetts by Gov. Elbridge Gerry, who wanted a favorable constituency for a run at Congress. The practice stretches back into at least the early 18th century, when leaders of the counties surrounding Philadelphia conspired to limit the city's influence in the colonial assembly, according to historian Elmer Griffiths. Pennsylvania, it seems, has always been a leader when it comes to tilting the scales of representative democracy.

The U.S. Constitution gives few requirements for how districts are to be drawn. Article 1 puts state legislatures in charge of the process but says little else about it. The 14th Amendment, and later court rulings based on it, require that each district have roughly the same population. Beyond that, legislators have been able to get away with almost anything. The motivation is the same as it was in Gerry's day: Friendly district lines can be the difference between an early retirement and years of easy re-election campaigns.

The word gerrymandering was coined in the 1810s to describe a particularly lizardy-looking district carved out of rural Massachusetts by Gov. Elbridge Gerry, who wanted a favorable constituency for a run at Congress.

What is new is the level of sophistication available to the lawmakers charged with creating the maps. Over the past two decades, political campaigns have steadily evolved in their ability to use demographic data to target individual voters. That same technology has helped political mapmakers draw ever more exact district lines. The adage about politicians getting to pick their voters has never been more accurate.

There are two basic strategies used for crafting a partisan map: "packing" and "cracking." Packing involves crowding as many of your opponent's voters into a single district as possible. North Carolina's 12th district—which winds from Charlotte to Winston-Salem and Greensboro—is a perfect example of packing Democratic voters into one weird-looking district, thus excluding them from the districts nearby. The packed district becomes, effectively, a single-party domain, while neighboring districts become more favorable for the other side.

Cracking is exactly the opposite. Pockets of demographically similar voters are separated into different congressional districts to eliminate their potential influence. This may explain why the famously liberal city of Austin, Texas, is split between three districts, all controlled by Republicans. Or why the relatively liberal enclave of Salt Lake City and its suburbs fall into four different districts, effectively leaving Utah's only significant population center without a representative in the U.S. House.

In Pennsylvania, Republican mapmakers packed as many of the state's Democratic voters as they could into just five districts: two in Philadelphia, another in a bluish part of the Philly suburbs, one in Pittsburgh, and a fifth that winds between several Democrat-heavy cities in the state's northeastern corner but excludes the redder areas outside them. Democratic leaders did not object much because party bosses in the state's two major cities got the districts they wanted. The 2011 vote to approve the map was a bipartisan one.

The biggest beneficiaries of redistricting are not the members of one party or the other but sitting office holders on both sides. "It's a multidimensional thing, but I think it all comes back to incumbents," says Olson. A party can safeguard key players and rising stars, and it can end the political careers of outsiders who buck the party line—all by shifting the map one way or another. Since state lawmakers draw the lines for members of Congress, redistricting is also a way to keep federal lawmakers beholden to their state-level party bosses. "Cross the leadership and you just might get cut into a tough new district next time," Olson says.

No Clear Line

The 2017–18 term is not the first time the country's high court has confronted this issue. In 2004, a group of Pennsylvania voters challenged an earlier set of Republican-drawn district boundaries on the theory that they unfairly disenfranchised Democrats. (Sound familiar?) In the end, the Court ruled in Vieth v. Jubelirer that it could not adjudicate claims of political gerrymandering for lack of a "workable standard" for identifying it. In a dissenting opinion, then–Justice David Souter proposed a multistep process to determine whether districts exhibited an "extremity of unfairness" toward one party or another. But the other justices were not convinced.

Each step in Souter's proposal, then–Justice Antonin Scalia wrote in his plurality opinion, required "a quantifying judgment that is unguided and ill-suited to the development of judicial standards." There is no clear line to indicate how much packing and cracking is too much, he observed, and courts should not be in the business of trying to sort out the motivations of partisan legislators. "The devil lurks precisely in such detail," Scalia wrote. "The central problem is determining when political gerrymandering has gone too far. It does not solve that problem to break down the original unanswerable question into four more discrete but equally unanswerable questions."

The current debate involves the same tensions highlighted 14 years ago by Souter and Scalia. Smart people often come down on different sides of the central question: Is it possible to apply objective, measurable standards to determine whether a district has been unlawfully gerrymandered?

Since 2011, Pennsylvania's 7th district has been cartoonishly shaped. David Daley, author of 2016's Ratf**ked: The True Story Behind the Secret Plan to Steal America's Democracy (Liveright/W.W. Norton), described it as looking like "Goofy kicking Donald Duck." It wound through parts of five counties, from the rural Amish farmlands around Lancaster to the heavily urbanized western edge of Philadelphia. In its January ruling, the state Supreme Court pointed specifically to that odd shape as an example of a district that is not compact.

Compactness is a term that gets thrown around a lot in redistricting debates. It can mean different things in different contexts, and there's probably not a single gold standard for measuring it, according to Daniel McGlone, a senior analyst for the Philadelphia-based mapping software firm Azavea. Yet it's a generally accepted principle among redistricting reformers that more compact districts are usually better than weirdly stretched or branched ones.

Math to the Rescue?

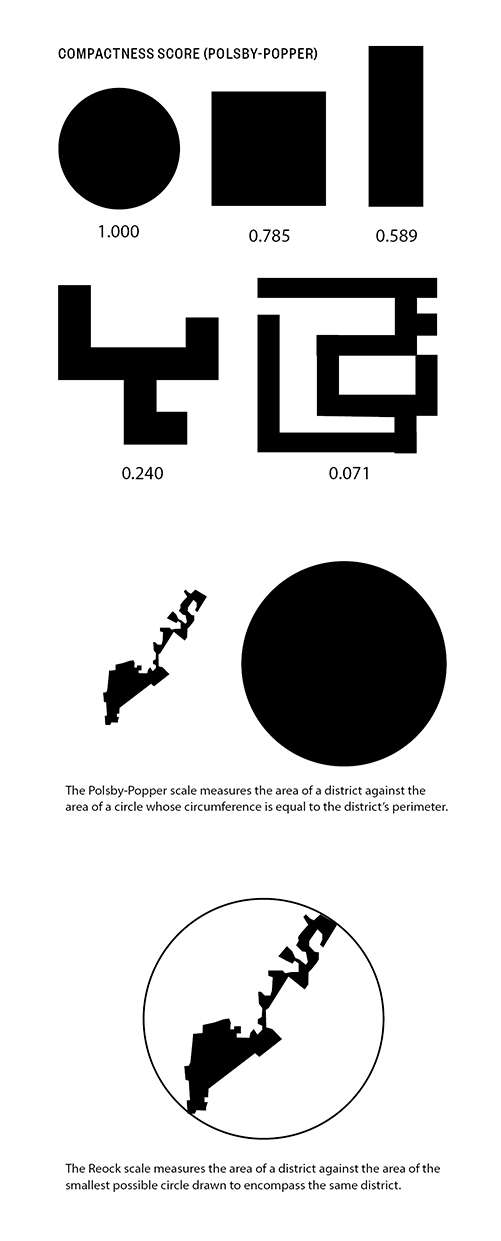

Various methods for calculating compactness have been proposed. The Polsby-Popper system, invented by two lawyers in the 1990s, compares the ratio of a district's area against a theoretical circle with the same circumference as the district's perimeter. That ratio indicates how much the district is indented on a scale of zero to one. The national average for a district is about 0.223, but the infamous Pennsylvania 7th scored just a 0.041, making it one of the least compact districts in the country.

There are other methods for measuring compactness as well. The Schwartzberg score is similar to Polsby-Popper, except it's the ratio of a district's perimeter measured against the circumference a circle whose area is equal to the district's. The Reock score requires drawing the smallest possible circle that would encompass all points of a district, then comparing the area of the circle to the area of the district.

These systems allow anyone with a map, a few basic drafting tools, and a calculator to score any district in the country. But looking only at the shapes can miss an important part of diagnosing a partisan political map: the outcome of elections held within it.

When a computer can spit out 100 different relatively fair and compact options, a map full of conspicuously partisan districts becomes harder to rationalize.

That's why another metric has gained currency in redistricting circles in recent years. Devised by Nicholas Stephanopoulos, a law professor at the University of Chicago, and Eric McGhee, a researcher at the Public Policy Institute of California, the "Efficiency Gap" is at the center of the Wisconsin redistricting case that is currently before the U.S. Supreme Court. To catch "packing" and "cracking" in action, it looks at whether districts are overloaded with voters from one party in order to boost the political fortunes of the other party in other places. Unlike purely geographical measurements, it attempts to quantify the partisan intent behind district lines.

The Efficiency Gap measure the number of "wasted" votes in each congressional district, defined as any vote for a losing candidate at all and any vote for a winning candidate above and beyond the number needed to secure a victory. The formula attempts to highlight partisan imbalance among all the districts in a state, with the underlying assumption being that districts should be as competitive as possible to reduce the number of "wasted" votes.

Working in its favor is this system's simplicity: No software is needed, just election results and basic math. But there are gaps in the Efficiency Gap. For one, it requires that elections be held before it can be employed. That makes it useful for determining whether districts are fair after they've been drawn and put to use, but it doesn't offer much help for how to go about drawing boundaries to avoid such problems in the first place. For another, the Efficiency Gap relies entirely on election results, which can be misleading. A blowout win in one district means lots of "wasted" votes for the victorious party under the Efficiency Gap model, but that doesn't necessarily mean the map was designed to bring about that outcome. A particularly bad opponent, a national electoral wave, or any number of other factors could give a false positive if the Efficiency Gap is the only metric you're using to decide whether a district is unfair.

Measures that seem more objective, such as Polsby-Popper, have shortcomings too. A congressional district that follows lines already on the map—geographic dividers such as rivers, or political boundaries such as municipal borders—is more likely to respect already-recognized communities and less likely to unnecessarily split up constituencies. But this salutary outcome may come at the expense of a better Polsby-Popper score. "Statistical compactness measures can have a problem because they don't look at the underlying geography," says McGlone. A perfectly round district would score a 1 in this system, but that doesn't make it ideal.

We have yet to discover a perfect method for deciding whether a district is "compact" or "fair," but the tools now available to judges, lawmakers, and activists at least offer a few ways to get at that question. Which is important, because as Scalia pointed out in 2004, gerrymandering will remain an "unanswerable problem" until courts have a way to define what it is and what it isn't.

'Redistricting Should Be Boring'

In their attempts to prevent partisan redistricting, many states have created "independent commissions" that empower supposedly disinterested members of the general public to craft maps, or at least to give input to the legislature.

Those efforts have had mixed results, with biases often managing to infiltrate a supposedly nonpartisan process. In California, for example, a highly touted "citizens commission" redrew congressional district lines in 2011, but a ProPublica investigation revealed that Democratic activists and labor unions had secretly packed the body to influence the outcome.

Even when they are not consciously sabotaged, citizens commissions don't do a very good job of un-gerrymandering districts. Researchers from Yale and the University of California, Los Angeles compared a set of 1,473 proposed district maps from 13 states where citizen input is part of the process against a set of maps created by computer simulations. After comparing simulated and actual election results using the different maps, researchers concluded that 77 percent of maps drawn by state lawmakers were less competitive than the computer-drawn alternatives—not very surprising, given the incentives for legislatures to create "safe" districts for incumbents. But the maps drawn by members of the general public were just as bad, with 75 percent of them being less competitive than their simulated counterparts.

So what if we took human beings out of the equation entirely?

"Redistricting should be a bureaucratic, boring process where you get the census data, you turn the crank, and you get new maps for the next decade," says Brian Olson (no relation to Walter), a Boston software engineer who has designed a computer algorithm to do exactly that. Olson's model uses numbers collected by the U.S. Census Bureau to ensure each district has the same number of voters and produces districts that are as compact as possible—garnering high scores on measures like Polsby-Popper and Reock—without regard for party registration or demographic information. Partnering with the website FiveThirtyEight, Olson then tweaked the model to show greater respect for existing political boundaries, such as county borders.

In his simulated map, there are few tendrils reaching out to snare extra pockets of desirable voters and, by design, no cities split three or four ways in order to eliminate their political influence. Any set of arbitrary lines on a map can be criticized for being drawn here instead of there, but Olson's algorithmic congressional maps are more compact and, according to a FiveThirtyEight analysis of likely election results, more competitive than what most states have now as well.

McGlone believes technology will play an important role in holding mapmakers accountable in 2021, when the next nationwide redistricting occurs. Azavea, where he works, is developing a program called District Tracker that will allow anyone to plug in freely available census data and draw their own congressional district maps. It's set to launch nationally later this year.

If the U.S. Supreme Court doesn't accept the Efficiency Gap as a bright line for ruling certain districts out of bounds, people will have to look for other ways to challenge maps they believe were drawn in bad faith. By giving average citizens and reform-minded organizations access to the same mapmaking tech that experts already use, Azavea and others make it easier for petitioners to provide courts and legislative bodies with alternatives to consider. When a computer can spit out 100 different relatively fair and compact options, a map full of conspicuously partisan districts becomes harder to rationalize.

Checking Our Worst Impulses

Stopping politicians and parties from using redistricting to preserve their power probably requires settling on an objective standard for determining gerrymandering. Fourteen years ago, the Supreme Court said such a standard did not exist. Now perhaps it does.

But even if the justices come to the same conclusion when they rule in the Wisconsin case that they came to in '04, lawmakers in any given state could take the initiative and create a gerrymandering standard on their own—forbidding districts with a Polsby-Popper score of less than 0.25, for instance. In comparison, the 2011 Pennsylvania districts averaged 0.16 on the Polsby-Popper and 0.28 on the Reock. The new Supreme Court–drawn map averages 0.30 and 0.43, respectively.

Setting a lower bound "would provide something like a fence," says Cato's Olson. "Gerrymandering could be as politically motivated as they want as long as they stay within the fence."

The Arizona Reapportionment Commission, overseen by a bipartisan collection of county commissioners, officially uses Polsby-Popper to evaluate proposed districts. Currently, there are no hard rules about what constitutes an acceptable score. If the commission did draw a line, critics would surely complain that its exact placement was arbitrary—and they'd have a point. But at least it would give both sides a clear understanding of where, to use Olson's term, the "fences" are.

Both parties should want to erect those fences now. Republicans took advantage of the opportunity afforded them in 2011 on the heels of the Tea Party wave. But who holds the reins of power could look different in 2021 and beyond.

It seems inevitable, especially in a hyperpartisan environment, that political parties will want to use every tool at their disposal to gain a redistricting advantage. That prospect should be worrying enough to convince lawmakers to place some limits on the process. Even if the five Democratic justices on Pennsylvania's high court had nothing but good intentions in tossing the 2011 map (which was, after all, plainly political), the appearance of partisan motivation is unfortunate in a case that's already entirely about competing political interests.

Will every subsequent change in the balance of the state Supreme Court mean congressional districts must be redrawn again to the majority of the bench's liking? If so, judicial elections in Pennsylvania just gained a new level of partisan significance—and the same thing could soon play out in other states. On the other hand, rules that a legislature sets for itself are less likely to create future constitutional crises.

One defining feature of American democracy is the intentional inclusion of elements meant to check politicians' (and factions' or parties') worst impulses. When those limitations do not exist, abuses like gerrymandering occur, inverting the all-important relationship between voter and representative. Removing self-interest from redistricting is probably impossible—too many people are too invested in the outcome of the process—but if we can finally get to a definition of gerrymandering, courts and citizens can start to do something about it.

"I don't think we're ever going to be able to take humans out of the process completely," says McGlone. But with technology, at least we can "shame politicians, or just show that it can be done better, done in a more collaborative way, rather than just by politicians behind closed doors." And with any luck, by limiting the nastiest abuses, we'll prevent a repeat of the current conflagration in Pennsylvania.

*Since this story went to press, the U.S. Supreme Court decided against reviewing the new district map drawn by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. The federal court offered no comment on the map or the process used to draw them, issuing only a one sentence statement by Justice Samuel Alito denying the Republican-backed bid to have the new map reviewed. In the wake the decision, some Republican lawmakers in Harrisburg have again discussed a longshot bid for the impeachment of state Supreme Court justices.

**CORRECTION: The original version of this story erroneously claimed that Walter Olson was a member of Maryland's redistricting commission in 2011. He was a member of the Maryland Redistricting Reform Commission, which met in 2015 to review the 2011 commission's work and to propose alternative methods of redistricting to Gov. Larry Hogan.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Gerrymandering Is Out of Control."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Here is a different approach, which is simple to accomplish and with profound but undetermined effects on political life:

1. Fix the appropriate number of voters to be included in an election district (let's say 100,000)

2. Have voters in a state randomly assigned to an election district (this means that an ED is virtual, having no relation to a location)

3. Any candidate can run in a any primary in any ED

4, The candidate can be told who are the voters in his/her ED, but will know little about them

Results:

1. No promises to bring money or jobs to an ED, since an ED does not physically exists

2. No pandering by candidates since they do not know enough about what their voters care about. Thus the candidate will have nothing to run on other that the candidate him or herself

3. All candidates (and thus all parties) will have to move to the center

As an aside, I propose having the ED's contain about 40,000 voters, resulting in a House of about 3 times the size it is now. That will make the cost of lobbying much harder, and will reduce the number of powerful lifetime Members.

Any thoughts?

Look! LOOK! A unicorn!

An interesting proposal that does deserve a serious look.

Of course, the pay of the legislature will need to be reduced, and the time they spend legislating will need to be increased as more people means a slower moving body.

Such a proposal would solve many issues, yet create more. People would decry it as throwing away key tenants of "democracy." Your congressman would no longer necessarily come from anywhere near you. People would claim that it disenfranchises voters.

Your proposal is far better than anything else, thus it will go nowhere.

Representatives are supposed to represent a locality, not a state.

You're correct that there are way too few of them though. In Germany for example there is one legislator for about every 100K residents versus 700K+ in the US. This seems a good size to me. Small cities like Erie PA won't get ignored in a vast sea of rural voters.

We need to increase the number of legislators, and lower their pay and perks.

Exactly.

Just one absurd detail in raz's plan: most families with multiple voters would have different representatives.

That is a GREAT detail. Why should families be forced to all have the same representative? They should be able to have as many critters as they have differing arguments about politics at Thanksgiving dinner. No one should have to lose their representation itself merely because they aren't in the majority on particular issues. Most people can accept winning or losing on a particular issue. What people can't and shouldn't have to accept is the notion that they will always be outvoted - on everything - always.

The number of representatives was capped, which turned out to be a terrible idea but since it concentrates power there's pretty much no chance that it will be reverted to it's original form. Unfortunately.

The number of representatives was capped at 435 by two laws of Congress - Apportionment Act of 1911 and Reapportionment Act of 1929. That's it.

I understand the duopoly and party establishment has no interest in writing a new apportionment act either now or following the 2020 census. But there is no reason why critters themselves cannot be made to make a campaign promise to actually reapportion and increase the size of the House. That is pretty much entirely up to voters themselves forcing it to become an issue and that can easily be across partisan lines.

Which yeah - is tough as long as voters are basically brainless partisan hacks who will only support what their preferred pols tell them to support. Hmm - ok yeah - it's impossible to change.

It won't be reverted because more Congressional Rep's means less power per Critter. It's pretty simple math.

Yes but. If they're elected because they promise to create and apportion a bigger more representative house, then that's what they'll do. They have to actively pass that enabling legislation after every decennial census. If they're elected without having to make that promise, they'll continue to do nothing re that.

This really ain't just up to congress on its own and in its own self-interest and its not pure math/undoable. It's up to voters to make it an issue. Obviously that itself ain't easy since most voters ARE brainless party hacks.

"Yes but. If they're elected because they promise to create and apportion a bigger more representative house, then that's what they'll do."

Right, like the Republicans who campaigned on repealing Obamacare? Or cutting spending?

Yes but. If they're elected because they promise to create and apportion a bigger more representative house, then that's what they'll do.

A politician keeping an election promise? One that would decrease his own personal power? What are you smoking?

Losing an election means losing power. Sure - if voters don't have the balls to hold their pols accountable to election promises, then it doesn't matter whether we even have voting or elections or a legislature or a constitution and we will deserve to lose all of it. Certainly that's where the brainless party hack voter is moving us. Question is - is there any other kind of voter? Maybe not.

JFree,

Go to http://www.boldtruth.com/

and see what the founders intended, and that there is a good argument for having included in the amendments.

It was, actually, the first one offered for the Bill of Rights.

Actually don't even need to reduce their pay. Right now Congress may have 530 elected critters - but there are 20,000 staffers. Most of those staffers exist only because districts are too large and complex for a single elected official to get a handle on. Constituent services, polling and election consulting, legislative specialists outside committees. And staffers are also the originating source of a lot of K-street and lobbying corruption.

Perks like pensions - yeah those should be eliminated.

You're exactly right regarding the number of legislators. I found this site several years ago that goes through the history of congressional districts, and makes the case that district sizes shouldn't be larger than fifty thousand:

http://www.thirty-thousand.org/

Finrod,

another site for that is: http://www.boldtruth.com/

And when you get assigned a rep 500 miles away just ignore your right to interface with your government?

Certainly agree with increasing the legislature size a lot but not sure what the other stuff does except to reduce information and representation.

Why not get rid of elections altogether and use random selection? That eliminates the need for gerrymandering but if they want to gerrymander districts that's OK too since it doesn't matter. Pick a voter in any district randomly and they are the critter. They speak and vote in the legislature for only themselves plus whatever the outcome of next paragraph. Also greatly reduces the number of sociopaths and power-seekers in office and increases the number of normal people.

Everyone else can use 'liquid democracy' and blockchain to allocate their preferred voting power inside the legislature to the randomly selected. eg critter A for local stuff, B for all war/peace issues, C for all issues relating to truckdrivers and D for everything 'cats'. That can be done/changed anytime for any reason. Blockchain just verifies each voters current preference. If voter has no interest in any of that, that's ok - the randomly selected critter is their neighbor (better w smaller districts).

Oh - and since this doesn't require elections it also doesn't even require a law to make it happen. Just some talent to create the structure - some to market it and make it known - and then let competition work to see whether people prefer this new type of assembly or their old legislature. The more people vote in one (and implicitly agree to abide by those decisions/laws), the less they will vote in the other. And the existing system can tolerate everything except - being ignored.

I've had a similar idea: random drawing of SSID numbers.

Your formulation is far more detailed and we'll thought out.

I'm on board.

The impetus for my original thought: a legislative body composed of completely randomly chosen citizens from throughout the US can't do any worse than Congress has performed.

That sort of system (called sortition) is actually how Athens functioned back in the day. It was Sparta that had elections. Athens thought that elections led merely to oligarchy (because it made buying elections both profitable and necessary).

We completely misinterpreted all of the ancient writings on governance and history because we didn't realize (or chose to distort) the actual mechanics of how demokratia (think of it more as consent of the governed rather than the modern word democracy) worked in both Athens and the Roman Republic.

Results 4. Candidates (and after election, politicians) will have even less incentive to care about the opinions and concerns of the constituents they are supposed to represent.

Results 5. Elections will be even more skewed toward well-funded candidates who can afford a statewide election and against poorer or non-professional-politician candidates.

An "election district" is a physical voting booth, and the area whose people vote at it. I think you mean a Congressional district. Congressmen are supposed to represent particular areas, not random assortments of people in the state. So this sounds like a very bad proposal. So does minimizing the so-called Efficiency Gap - there is no reason to desire districts that are divided 50-50 between Democrats and Republicans. There are algorithms for dividing an area (a State) into a given number of districts which would have maximum "compactness". One of them should be chosen and adhered to.

I like your idea. The downside I see is that in many states where the split is 70/30 or 65/35, gerrymandering will almost always result in at least 5-10% of the districts voting for the minority party. In the solution you propose, it would be very easy to see the minority party achieving 0% representation.

I don't really like the idea of our representative in Washington being closely tied to a small geographical region. It seems like it increases incentives to add earmarks for local projects.

My proposal would be to do away with districts completely instead of having virtual districts. After all the votes are in, you can divide the votes along party lines, choosing candidates with the most votes until you reach the proper percentage of representation.

For example: A state has 12 seats. 1/2 of the vote is Democrat, 1/3 republican, and 1/6 Libertarian. Therefore 6 seats would go to the 6 Democrat candidates with the most votes. 4 seats would go to Republicans and 2 to the top Libertarian candidates.

The down-side of this is that if you are independent and your top 5 choices are a mix from all 3 parties. It also increases the number of people running to the point where no one would research each candidate and would simply vote along party lines. Maybe ranking candidates within a party would be done through party caucus meetings? I don't know how to solve all problems. I just think this would be better than our current system. Thoughts?

Take party affiliation out. If a state has 18 seats, then the seat seeker has to get at least 15% of the of the 30,000(Article 1,Section 2)or what ever amount is established, in signatures to be placed on the ballot. The ballot will contain the name and city/town of the office seeker. Each voter will get to choose just one name. The top 18 get to serve. No primaries required.

The PA Legislature is moving forward with impeaching some of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court justices too.

Which they should. The federal Constitution is clear on who makes the maps. It is one thing for a judge to toss a map and an entirely different thing for them to create a map. Can you imagine the outrage if the judicial branch started appointing and confirming Trump's cabinet because Congress won't consent to them? It's essentially the same demand they gave the legislature for the maps.

The correct way to fix gerrymandering is with a constitutional amendment.

Judges have become entirely too comfortable lately with legislating from the bench.

Or, Republicans have become too comfortable legislating unconstitutionally.

Judges rarely void laws because they are unconstitutional and send the entire bill back to the legislature. The courts like to unconstitutionally "fix" the law. Like with the unconstitutional ObamaCare.

Or maybe courts, for now, don't operate according to a tribal grudge instinct quite so much as you do. As in, if Bush passed Bushcare and it were identical to Obamacare, you'd love it, and don't pretend otherwise.

Tony, you're projecting your own unreasoned, irrational partisanship onto others.

As in, if Bush passed Bushcare and it were identical to Obamacare, you'd love it, and don't pretend otherwise.

You can tell that by how popular Bush's TARP program was here compared to when Obama bailed out the auto makers.

Actually, both moves were shit and most people here said so.

I was talking to a specific poster who probably believes that TARP was an Obama program.

"Like with the unconstitutional ObamaCare."

Do you say this because you find anything you don't like "unconstitutional", or is it just that you don't understand the Constitution?

A constitutional amendment that will never happen because districts are already severely gerrymandered and you need a super-majority for a constitutional amendment. That's a great solution if you have no interest in fixing the problem.

What problem? Be precise. What is the glaring problem you see that should be remedied judicially and not through the proper mechanisms.

What problem? Be precise. What is the glaring problem you see that should be remedied judicially and not through the proper mechanisms.

The problem of not having representation if you are in a cracked or packed district.

My constitutional amendment to limit gerrymandering:

No Congressional District shall be drawn that does not cover at least half of its state's land area inside of east-west lines through the northernmost and southernmost points of the District, and north-south lines through the easternmost and westernmost points of the District.

It's very similar to their circle, except it uses a square and it doesn't need a computer. You could check whether districts pass this test with a printed map of the district, a straightedge, a pair of scissors and a balance scale.

Well, rectangle not square. (My kingdom for an edit button.)

We're fixating on redistricting because it's screwing Democrats.

They need an excuse, an edge, anything.

Republicans have managed to redistrict THEIR states in ways that no longer put THEM in control. Republicans have had control at the crucial post-census points

And that's why we're talking about this.

You can tell because 'fair' has risen it's head. It's not fair....that Republicans get to do the thing WE like to do!

Phrases like "there are a million more Democrat voters" leaves out 'all crammed into a tiny area'.

See, those county by county vote maps show an uncomfortable truth. The vast majority of the country--the people out living on the land--are NOT Democrats and they don't want themselves OR their land controlled by Democrats.

There might be 400 people living on a million acres out there who don't want to lose control of their farms and ranches because the nearest population center is full of soft-brained Democrats.

Fair is letting the districts shift as they have since almost the dawn of the country. Fair is NOT stopping the process because the party that needs it to maintain power has lost control of it.

Land doesn't vote. People do.

Right, that's why, because the population of the US is a small fraction of the US plus China, China should rightfully control the US plus China. Because land doesn't vote.

People in one place don't want to be ruled by people in another place. THAT is the issue here.

This is a great point. 'Majority rule' is not the core principle this nation is based on. Rather, America is based on the principles of individual liberty and self government.

It's not fair the California and Texas are so powerful so we have to redraw the states to have equal population! This is the same argument that the Democrats are making only on the state level.

State decide how their voting systems are setup. They can switch to counties decide all political wins except for the House of Representatives.

No, they can't. The Supreme court ruled that unconstitutional.

What case is that where the SCOTUS decided that states cannot determine state elections by using majority wins in counties carries the counties and the most counties wins the political position?

Reynolds v Sims.

I have never understood what the purpose of a state senate is. It's just another layer of government only slightly more removed than the state assembly or house or whatever.

The purpose was to be an analog to the US Senate. You have one chamber apportioned by population, the other by geography, so that bills must both be popular, and have reasonably distributed support, in order to pass. Same point as at the federal level.

Reynolds v Sims did render state Senates redundant, it was a common complaint after the ruling.

And that was before I was born - I didn't know it used to be otherwise.

Yah I get it. I meant it was never like that in my lifetime & I didn't know it used to be differnt.

Thanks. Looks like that case needs to be overturned. It was the Warren Court and was more concerned with getting rid of segregation than maintaining checks and balances to government power.

The dissent was right, it removes safeguards of a republican government all the way down to a local level. The 1 person 1 vote fits the state Houses and US House fine and makes sense but not fit the intended purpose of the state Senates and US Senate.

State Houses could be based on population while State Senates based on counties, just like the House of Rep was based on population and the Senate was based on 2 per state.

The Senate in the state is a check and balance to the state House or equivalent. The US Senate is a check and balance to the US House.

Alas, I think Reynolds v Sims falls into the "you can't unscramble an egg" category. Once you give the cities control over the whole state, they won't give it up.

You can. You just need more justices like Gorsuch who are more originalist. I do not know his particular position on this issue but this court decision is not necessarily constitutional.

I don't think so; Most states will have explicitly amended their state constitutions to comply with Reynolds v Sims, so the Supreme court merely permitting the old system wouldn't change anything.

And they're not going to mandate a return to the previous system, there's no basis for that. It would have to be a state level amendment in each case, and again, the problem is that the politicians elected under the present system wouldn't agree to that.

No - the Senate in a state does not have the same check-and-balance function as the original (or even direct-vote) Senate at the federal level because it does not have the same separation of powers function.

The US Senate had/has specific enumerated responsibilities that derive purely from state-level authority:

Appointment of federal judges opining on and potentially overriding state law.

Declaration of war which was supposed to require state militia to become federalized for the duration

Ratification of treaties with foreign powers which creates both federal and state level law.

Those are all good reasons for selecting senators via state legislature appointment - but direct vote doesn't change those enumerated responsibilities either.

There is nothing comparable at the state level. They merely copied a bicameral legislature. Counties are entirely a creation of and legally subordinate to the state so there is no separate legal interest cuz no separate legal system.

Brett, thanks for the case law. I meant to add what constitutional authority the SCOTUS had to do that and it looks like none.

Making the state Senates redundant via a court decision would call into question the validity of the court decision since the Founding Fathers were not known for adding redundant forms of government.

I mean that is true that most rural America does not want Democrats representing them but the districts are supposed supposed to be based on people not land. That is why there are two houses in Congress where the Senate was supposed to represent the states because Senators were appointed by state Legislatures.

Having all voting by county for all political positions except Congressmen would fix that problem. State carries president base on counties won not population, for example.

So what you're saying is that states should gerrymander their counties instead of gerrymandering their districts and everything will be OK and all problems will be solved.

Ya sure ya betcha

The efficiency gap isn't actually a measure of gerrymandering. It's a measure of how close you've come to producing districts that would replicate the effect of proportional representation. In theory, you could achieve an efficiency gap of zero while having districts that look like an Escher tiling, literally shaped like salamanders. It would actually make lowering the efficiency gap easier! In most states a zero efficiency gap can't be achieved without deliberately violating normal districting rules like compactness.

In truth, the real meaning of "gerrymandering", if it isn't weird shaped districts, is just drawing the districts to produce a particular political outcome. If you need to know how people voted in past elections to draw the new districts, you're gerrymandering.

The reason Democrats like the efficiency gap, is that the fact that they tend to cluster in cities, while Republicans tend to be spread out all over the place, causes them to be disadvantaged in redistricting. If you draw the districts without any regard to political effects at all, you'll generally get a map that hurts Democrats.

Using the efficiency gap to define "gerrymandering" gives the courts an excuse to engage in actual gerrymandering to negate this natural disadvantage Democrats are under.

Yes, the court actually committed gerrymandering in PA. They produced a map that was actually more favorable to the Democrats than the map the Democratic party itself had proposed!

Gerrymandering is bad, politicizing the courts is worse. Of course, politicizing the courts is a totally unintended and unforeseeable consequence of giving the courts this power, nobody could possibly expect it. It's not like judges are venal and corruptable just like every other human being.

It's like mandating direct election of Senators rather than allowing the state legislatures to set the process, the state legislatures were venal and corrupt and some of them would sell the office to the highest bidder so instead we have the venal and corrupt populace selling the office to the highest bidder. Fundamentally changing the nature of the Senate from a body jealously guarding the sovereignty and the prerogatives of the state to a body offering free shit to the citizenry just like the House hasn't worked out so well if you ask me.

Are you insinuating something here? What? Being judgmental, perhaps, are we? Condemning those who pander to the Gerrymanderers?

Watch OUT, buddy, or ye will be known as a...

"Gerrymanderer panderer slanderer"!!!

And ye may NOT do this without the approval of your Betters in Government Almighty! There are those who supervise this function, for the safety of ALL, and they are known as the...

"Gerrymanderer panderer slanderer commanders"!!!

Hey! Political nerds have hearts, too!

Given that people self assort into like-minded communities, and that republicans and democrats don't overlap as much as they used to, wouldn't you expect a "natural" district to be heavily biased? The only real measure of fairness is whether the legislative body reflects the population split.

If the Democrats don't want to be gerrymandered out of state politics maybe they might consider not living all clustered together in cities, from where they wish to lord it over the rural territories they don't live in by sheer weight of numbers.

It's easier to have a corrupt government in dense population centers.

Yes, because people are randomly born Democrats and they all eventually migrate to cities. Not that people who live in cities tend to be Democrats because big government appeals more to people who live among lots of other people. That would make too much sense.

And it makes equal sense that people who live in smaller areas will be Republican.

It's just that Democrats won't leave the Republicans alone.

Ask California farmers how great life is with LA and SF running the state.

Yeah but OK Republicans from the countryside control everything and are making laws that affect me. It goes both ways. How can you possibly not understand that?

Is "rural Republicans control everything" the Democrat version of blaming the "deep state"?

Welfare is the all powerful magnet.

Yep. Democrats are not geographically diverse. Sucks to be them.

" Over the past two decades, political campaigns have steadily evolved in their ability to use demographic data to target individual voters."

Sounds like Cambridge Analytica.

So, when do we crucify them?

They already are. Population social graphing was cool when Obama did it, evil when Republicans do. Gerrymandering was cool for 50 years when Democrats controlled the process, evil after 2010 when Republicans did.

One of the advantages of having nearly 100% of the people in your district of the same party, is that your representative might actually represent you.

Is it really great to make every district competitive, guaranteeing that nearly 50% of them lose every time?

It seems like the real solution would be to abandon geographical boundaries as a districting mechanism altogether.

True. But I've always wondered about those nearly 100% Democratic districts. Are they 100% Democratic because Democrats are the best fit to the local population? Or is it because once Democrats take control of a local government, they drive everybody else out or into hiding?

I suspect it's some of each, but with a big helping of the latter.

The only districts that are 100% Democrat are also 100% "minority". Trump, for example, got something like 40% in my Brooklyn district, and won outright in some others.

OTOH there is a lot of hiding too. On both sides.

The only districts that are 100% Democrat are also 100% "minority". Trump, for example, got something like 40% in my Brooklyn district, and won outright in some others.

OTOH there is a lot of hiding too. On both sides.

The efficiency gap metric is just plain idiotic. Number of reps and proportional districting is determined by a ten year census. In a ten year period people move. The efficiency gap measures total number of votes which is population eligible multiplied by percentage of voting. It refuses to acknowledge voter enthusiasm and would tilt elections to urban areas where voter percentage are higher since it's easier to mobilize population dense areas. The efficiency gap is purely an attempt to harm rural areas.

The efficiency gap metric is just plain idiotic. Number of reps and proportional districting is determined by a ten year census. In a ten year period people move. The efficiency gap measures total number of votes which is population eligible multiplied by percentage of voting. It refuses to acknowledge voter enthusiasm and would tilt elections to urban areas where voter percentage are higher since it's easier to mobilize population dense areas. The efficiency gap is purely an attempt to harm rural areas.

Given our America confusion of sports and politics, let's turn districting into a draft. Divide a state into a grid, with the number of blocks at least 10 times greater than the number of reps. Then let each sitting rep choose a block in the first round. In subsequent rounds, each rep chooses more blocks but with the rule that his or her blocks must be contiguous. Televise the whole thing with pundits and commentary.

Interesting idea, but it runs afoul of the constitutional requirement that districts have equal population, where your approach provides equal geographic area.

Easy enough to fix. Once a candidate hits the minimum population for his district, he's done. Might have to be some minor adjustment with fractional squares to hit the pop dead-on, but that wouldn't be too difficult to assist for.

It would look a little bit like a game of Carcassonne. What happens when an incomplete district is surrounded by claimed blocks?

All you're really saying is that instead of having legislatures draw lines on the map you're going to outsource that to some unaccountable computer programmers instead. That really doesn't seem like much of an improvement.

Well legislatures will create districts that the programmers will need to run in, to get elected, to create the code, to draw the lines, to elect the legislature, to swallow the spider, to catch the fly. Why oh why did we ever swallow that fly.

All you're really saying is that instead of having legislatures draw lines on the map you're going to outsource that to some unaccountable computer programmers instead.

There are many people who work at Facebook who think that's a wonderful idea.

If you give the job to me, I'll do it exactly the right way.

Just one thing - do I have to include every teensie inch of the land in the state?

This article, when talking about Pennsylvania, mentions that the Democrats won the state generic ballot in the 2012 election (by a narrow margin), but failed to mention that the Republicans won the congressional generic ballot in 2014 and 2016 by 11 and 8 points respectively. But now the PA SC is going to impose a map that might give the Democrats a majority of PA's US House seats? Give me a break.

This is politics pure and simple.

When a single party controls the Legislature, Governorship, and the courts gerrymandering problems are rarely upheld.

Pennsylvania is a big deal because its a swing state and Democrats are losing control of it.

Controlling the state Legislatures tends to be the better move and Republican control 32 with 4 more split legislatures.

I realize most of you idiots lack the capacity for empathy at any level--it's why you're here--but just try to imagine a counterfactual scenario, if you can. Imagine that Democrats control the House of Representatives and Senate despite winning millions fewer votes. Imagine we have President Hillary who lost the popular vote. Would all of you GOP footlickers be saying "Well we're not really a democracy," and "That's the way the cookie crumbles!" so uncaringly? You already think Democrats want to spoil your precious bodily fluids even without them having any power. I doubt you'd take such a scenario lying down. So don't act surprised when actions are taken to restore some measure of fairness and democracy to the system.

Imagine there's no strawmen, it's easy if you try.

What we GOP footlickers say is that the federal government is too large and that the outcomes of federal elections

should matter so little that these issues become immaterial.

Oh, we have empathy alright, but we make a conscious effort not to misapply it to politics. For example, I empathize that Democratic losses make you feel bad and that you generally must feel totally miserable in your life, but I'm making a conscious effort not to care.

YEAH! WHY WON'T YOU IDIOTS SHOW A LITTLE EMPATHY FOR ONCE??!?!

You have learned so well from David hogg these last few weeks.

Fuck off, slaver.

Most of us want to take away the possibility of anyone having the awesome power of the state levied against them.

I fully support anyone who want's to have a relationship with whatever you want. If you want to invite me to your wedding with your giant high def 3d flatscreen, I'll be there with bells on and happily celebrate your different take on life.

You keep wanting libertarians to be Republicans, and most of us aren't. We just don't want anyone to be forced into lifestyle choices by someone else.

You've seen through our mask: our opposition to the criminalization of poverty (for example) is driven by our privilege and lack of empathy.

Of course!

Computers drawing districts based on census data "adjusted" by congress is a great idea.

What could possibly go wrong?

Multi-seat districts with a more nuanced method then "first past the post" solve 99% of these problems.

May I humbly suggest:

legislation for drawing voting district boundaries shall be along the borders of the next smaller government entity, or contiguous entities, except when the population demands that the smaller entity border be transected. In that case, the dividing line shall be exactly that. A line: 1) Drawn straight from one border of the smaller government entity being divided to any other border of that same entity. 2) When the border of the next smaller government entity would be divided by that line, all residents shall be assigned together to either one or the other district. 4) This shall continue down to and including residential property, so that no residents of an single property vote in different districts.

Perhaps this algorithm is simple enough to satisfy the critics. Perhaps it is complicated enough to satisfy the wonks. Certainly the mathematicians and the lawyers would love the employment potential! And the judges could finally catch a break. Every 10 years, the incumbants would have something to occupy their time, diverting them from inventing ever more silly laws. And district maps would be a tad prettier, leaving political reporters time to find more cash in the freezers of politicians.

My rep is John Lewis (D). Literally across the street, the rep is Karen Handel (R).

I'm f'ed either way.

Oops, that wasn't meant to be a reply

Ok, just don't ever ask for majority-minority districts ever again, or complain that blacks cannot win without such districts.

The creation of majority-minority districts or at least packed-minority districts was a Democratic gerrymandering impetus, which was welcomed by Republicans as it tended to remove Democrats from other districts, making them more Republican.

Gerrymandering for this racist purpose was just hunky-dory for Democrats when they were in charge.

P.S. I've heard/read a depressingly large number of people who complain that it was gerrymandering by Republicans that won Trump the White House. I guess they think that state borders are redrawn every ten years?

I've also heard/read a depressingly large number of people who say something like "Republicans only win because they've gerrymandered the state i their favor."

Of course, totally ignoring the fact that Republican could not gerrymander a state until AFTER they'd won a majority to accomplish the gerrymandering. The gerrymandering can cement future wins, but can't happen until the bloc has already achieved a majority, or at least the self-serving support of enough of the minority (who might be guaranteed of winning their own new district cram packed with their voters).

mpercy - that really is the issue. What does winning an election actually entitle you to do? It's entertaining that the triumphant 'elections have consequences' phrase no longer seems so wonderful...

Should winning an election guarantee winning future elections even if the demographics of the district change? That's what extreme gerrymandering does.

Should winning an election allow you to fund NPR as a nationwide advertising campaign? How about endlessly empowering public unions and public schools that are increasingly used to indoctrinate?

In my mind gerrymandering fits nicely into that realm, and I'd really like to reduce the size of the federal government so it doesn't matter all that much who gets elected. Whining about one aspect of a complete insane government feels like a big yawn.

The effort to impeach justices in PA is dead, killed by GOP state legislative leaders today.

Gerrymandering is so out of control because the Gerrymanders have computers to better enable their Gerrymandering.

GIGO!

Garbage-in would result in random 'manders.

Let me make a couple of points here.

Drawing up districts is inherently political. I like the way Kevin Williamson puts it:

A little more than 20 years ago, the Texas legislature was afire with controversy surrounding a redistricting project. Advertising my ignorance of the process, I asked a veteran state legislator at the time whether he thought the redistricting process was "politicized." No, he explained, it isn't politicized ? it is political. "Redistricting is the most political thing a legislature does," he said.( http://www.nationalreview.com/.....od-not-bad ).

This is the 1st reason that the courts should stay out of the process.

The "efficiency gap" is junk science.

"The result of these various problems is that judging district lines by the efficiency gap will produce an intolerably high number of false positives and false negatives. That is, the efficiency gap will sometimes conclude that honest maps are partisan gerrymanders and sometimes conclude that partisan gerrymanders are honest maps. In short, this is not a formula that justices should feel empowers them to make nationwide judgments on what is and is not an impermissible partisan gerrymander.

( http://www.weeklystandard.com/.....le/2010051 )

P.S. Is there any way of formatting comments here?

Limit the number of counties that be represented by a congressional district.

More than half the counties in Oregon have a single Congressman, because the population of those counties is low. Wyoming has only one representative for the whole state, and so, I think, does Alaska. So however many counties those states have, all have to be in the same district.

For Alaska that's okay, because there are no counties!

I always have wondered why the number of congressmen should be limited to 435. If there were twice as many districts, it would be harder to make rediculously shaped ones.

So each congressman can have more power.

The main reason House size was limited initially was to limit new voices and keep party establishments in control. eg When women got the vote, that doubled the size of the voting population. Keeping the legislature constant when suffrage is being expanded (women, immigrants, blacks, youth) forces a zero-sum game - a challenger has to eliminate an incumbent. There are no new seats anymore. So the demographic in power gets to keep power.

With party establishments, a smaller legislature is easier to control by rationing out committee assignments, campaign funds/assistance to help with larger districts, etc. And those who want to buy Congress find it easier/cheaper to buy fewer critters than more critters - and the larger the district the more incumbents/challengers depend on getting the support of big money before they can even start to think about campaigning.

Have you seen parliaments that have over 500 members. Its a madhouse when debates happen.

When the Republicans amend the Constitution soon, one of the changes should be to change how many Americans are represented by a single congressman from 50k to 100k.

Psst, it's now about seven times that, so what would your amendment do?

Sorry but this is a total load of crap. I think it ironic gerrymandering, which allowed Democrats to hold the House and Senate for DECADES last century is suddenly a problem because their insane leftist policies have resulted in them losing control of many state legislatures which draw the districts. I am not willing to trust a computer to draw districts when we have many recent examples of how easy it is to hack and manipulate computers remotely. The process was not an issue until Democrats began losing elections they were convinced they should win because the have the media as their unpaid but reliable mouthpiece. When voters stopped listening to and trusting the media, Democrats started whining about gerrymandering. When Democrats lost more than 1000 seats in State legislatures and found themselves in control of only 16 state legislatures and less than 25 governorships, gerrymandering was to blame. Since Pelosi who has said Democrats would retake the House in every election since 2012 and yet was wrong, gerrymandering is to blame. When Reid insisted Democrats would not lose the Senate and then did, gerrymandering is to blame. The reason democrats lose elections is they push a big centralized government agenda intended to restrict and/or strip us all of our liberty and force us to bow in allegiance to all powerful state they seek to create.

The worm will turn. That's what worms do. Democrats are whining now because they think it will gain them more political power. It's no different that a 6-month old baby. It may work or it may not. That depends on how easily manipulated the voters are and how spineless Republicans are.

" When Reid insisted Democrats would not lose the Senate and then did, gerrymandering is to blame."

You lose credibility when you ascribe obvious nonsense to your opponent. Gerrymandering is objectively not relevant, in any way, to the U.S. Senate.

Gerrymandering afflicts both political parties. It should offend people who value fairness and justice, whichever political party they might belong to (or not).

Government works best when people with different viewpoints work together to solve problems (because the different viewpoints cover blind spots.) But non-competitive districts produce representatives disinclined to work with people of different viewpoints. Gerrymandering takes competitive districts and makes them less competitive (in both directions). This is bad, even if it puts more of "your" guys in office.

"When Reid insisted Democrats would not lose the Senate and then did, gerrymandering is to blame."

How does gerrymandering impact the Senate when Senate elections are statewide?

"When Democrats lost more than 1000 seats in State legislatures and found themselves in control of only 16 state legislatures and less than 25 governorships, gerrymandering was to blame."

Similarly, how does gerrymandering impact Governor elections, which are also statewide?

Guys, you need to read the whole thing.

This--

Let's you understand that this is what Democrats are blaming--

Because they don't want to face this--

Which is a pity because it tells you something important. Republicans wrested control from Democrats in districts that they'd already severely gerrymandered to keep themselves in power. That should be a warning bell--no, a warning klaxon shrieking that they are in grave danger.

No matter what Reason's liberaltarians might think.

"Guys, you need to read the whole thing"

Maybe you should read all of mine?

The reason Leftists won't subscribe to the metric of compactness as the identifying feature of fairness is that they desire to maintain an implicit bias in their favor in the form of majority minority districts.

If political bias is to be removed from the process, calling out Republican bias while somehow sanctifying their own use of bias is, as the norm, the smug and unprincipled calling card of the Leftist asshole.

The reason Leftists won't subscribe to the metric of compactness as the identifying feature of fairness is that they desire to maintain an implicit bias in their favor in the form of majority minority districts.

If political bias is to be removed from the process, calling out Republican bias while somehow sanctifying their own use of bias is, as the norm, the smug and unprincipled calling card of the Leftist asshole.

You'd get a lot of non-republicans to agree to sacrifice majority-minority districts if un-gerrymandered districts would allow more representative government.

"they desire to maintain an implicit bias in their favor in the form of majority minority districts."

The flaw in this argument is that minorities aren't implicitly "Leftist". Ask the Cuban-Americans. Or the "boat people" who fled Vietnam in the late 70's and early '80's.

There is an obvious solution to gerrymandering.

It's this: Let the second-largest party in the legislature draw the districts.

If they're successful in drawing districts to their advantage, they'll stop being the second-largest party, and lose the power to draw districts. If they stay the second-largest part in the legislature, they keep the power to draw districts but lack power to do anything else.

Now, that's not to say that this scheme wouldn't have its own problems, but you wouldn't have the party in power drawing districts to keep itself in power, regardless of what the people in those districts want.

check more about gender marriages and other issues in this transgender essay

My pet idea: district boundaries are a series of parallel lines, spaced for equal population. After each general election, the orientation of the lines changes by some fixed amount, perhaps the golden angle.