The Originalist Case for Jury Nullification

Is there a place in our system for a jury to acquit because the jurors believe the underlying law is unconstitutional?

Does jury nullification undermine the rule of law? Or is there a proper place in our criminal justice system for a jury to acquit, not because the jurors believe there is insufficient evidence of a defendant's guilt, but because they believe the underlying law is unconstitutional?

The conservative legal writer Mark Pulliam and the libertarian law professor Ilya Somin have been debating these questions this week. Pulliam views jury nullification as "brazen lawlessness and a prescription for arbitrariness." As he puts it, "if a juror (or any other member of the political community) feels that a particular law is unjust—and in a society as large and diverse as ours, we can assume that someone, somewhere, feels that every law on the books is unjust—the remedy is to petition the legislature for reform, not to infiltrate the jury and then ignore the law."

Somin concedes that nullification may undermine the rule of law in some cases, but that's a price he's willing to pay. "In the real world, law enforcement is already characterized by wide-ranging discretion, because we have vastly more laws than we can possibly enforce," Somin writes. "With so many lawbreakers to choose from, police, prosecutors, and politicians cannot avoid exercising wide-ranging discretion about which ones to target and which ones to let go. For this reason, jury nullification is not introducing an element of discretion in an otherwise rule-bound system. Rather, it serves as a counterweight to the enormous discretionary power already wielded by government officials."

Somin makes several good points. He could have added that nullification has a historical pedigree that should impress constitutional originalists. There's good evidence that many 18th and 19th century Americans understood juries to possess the lawful power to reject guilty verdicts when the jurors believed the underlying law was unconstitutional.

Consider the writings of John Taylor of Caroline. A Revolutionary War veteran and widely read political and constitutional theorist, Taylor described juries as the "lower judicial bench." Under this view, just as judges (the "upper bench") possess the power to declare laws unconstitutional, so too do juries (the "lower judicial bench") possess their own version of a veto power. In other words, just as both the Senate and the House get to vote on legislation, both the upper and lower judicial benches get a say-so on the constitutionality of legislation. Juries, Taylor wrote, "judge really and substantially in every case."

James Wilson, a signer of both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, made a similar point in his 1791 lectures on law at the College of Philadelphia. "Whoever would be obliged to obey a constitutional law, is justified in refusing to obey an unconstitutional act of the legislature," Wilson said. "When a question, even of this delicate nature, occurs, every one who is called to act, has a right to judge." Juries, of course, are "called to act" in our criminal justice system.

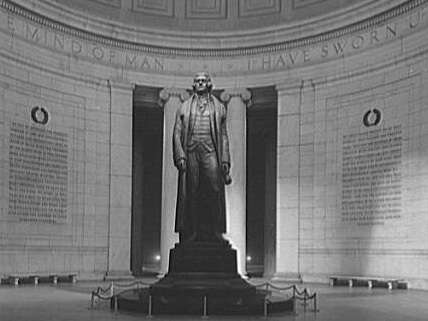

Thomas Jefferson, in a 1789 letter to Thomas Paine, expressed what many members of the founding generation thought about this issue. "The trial by jury," Jefferson wrote, is "the only anchor ever yet imagined by man, by which a government can be held to the principles of its constitution." How might a jury do this? By standing as a bulwark against overreaching government and by refusing to enforce unconstitutional laws. No jury is going to anchor the government to its constitutional principles by mechanically carrying out the government's bidding. As that famous observer of early American institutions, Alexis de Tocqueville, concluded in Democracy in America, the jury "places the real direction of society in the hands of the governed, or a portion of the governed, and not in that of the government."

Perhaps we should not think of jury nullification as a bug in the system. Perhaps we should think of it as a feature.