In Memoriam: Marcus Raskin, Radical and Decentralist

His critique of concentrated power is still relevant today.

When Marcus Raskin died over the Christmas holidays, his obituaries may have made him sound like a fairly typical left-liberal figure. He had a job in the Kennedy administration. He co-founded the Institute for Policy Studies, described in his New York Times obit as "a progressive think tank." He was active in the '60s antiwar movement, and his son is a Democratic congressman. He clearly was more militant than your average liberal: That Times piece mentions that he played a part in the leak of the Pentagon Papers and that he went on trial for "conspiracy to counsel young men to violate the draft laws." But there's nothing there to suggest his condemnations of state power ever went further than that portion of the state that was waging an especially stupid war in Vietnam and drafting American kids to die there.

But in the '60s and '70s at least (I'm less familiar with his later work) he staked out a much more anti-authoritarian position than that. If you pick up Raskin's 1974 book Notes on the Old System, you'll find that it's largely an attack on presidential power—not just in the hands of Richard Nixon, but in the hands of the progressives who built up the imperial presidency before Nixon entered the White House:

Since 1933, the United States has been in a declared state of national emergency and crisis. During this period Congress delegated, through 580 code sections, discretionary authority to the president "which taken all together, confer the power to rule this country without reference to normal constitutonal processes."…Under the powers delegated by these statutes, the President may seize properties, mobilize production, seize commodities, institute martial law, seize control of all transportation and communications, regulate private capital, restrict travel, and—in a host of particular and peculiar ways—control the activities of all American citizens.

His days butting heads with hawks and technocrats in the Kennedy administration had radicalized him: Raskin became a part of the New Left revolt against liberalism. And unlike, say, the Weathermen, his wing of the movement mostly stuck to revolting against the right things: the imperial presidency, the national security state, the partnership between the government and the great corporations ("It has been a cardinal principle," he wrote, "that big business helps big government and vice versa"), and a host of measures that concentrated power in Washington, D.C. "From the end of the Second World War," he complained in Notes, "liberals provided the music for the corporations and asserted the need for a strong national leader who would operate benevolently through rhetoric and the bureaucracy for the common good of the System. His powers would verge on the dictatorial." He didn't just reject that approach to power; he rejected a lot of its fruits too. "Lyndon Johnson was a master at managing bills through the Senate which were thought of as reforms, but whose fine print left the major institutional forces of the society untouched, or even greatly reinforced. Appropriations for Great Society programs seemed designed to help the wretched but turned out in practice to meet the needs of the 'helpers,' the bureaucracy and the middle class and the rich."

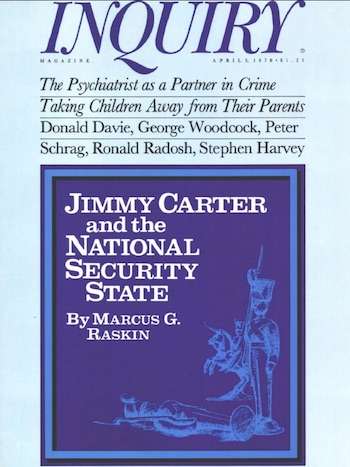

Raskin was a man of the left: He wanted society to challenge corporate capitalism and to assure minimum levels of well-being. But not necessarily through the federal government. Notes instead calls for a decentralized participatory democracy; the book doesn't get into details, but you can guess the general outline of what the author wanted from the fact that he takes to quoting the Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin. Couple that distrust of centralized power with Raskin's sharp critiques of his old colleagues in the national security establishment, and you can see why several libertarian figures of the 1960s and '70s saw him as a potential partner. Karl Hess, Murray Rothbard, and Leonard Liggio gave lectures at the Institute for Policy Studies, and the institute helped sponsor Hess's Community Technology project. Raskin in turn served on the board of the National Taxpayers Union and contributed a cover story to the Cato Institute's Inquiry magazine. Many different flavors of radicalism had their advocates at the institute while Raskin was running it, but the ones whose ideas seemed to be closest to his heart hailed from that grand old forgotten left/right/libertarian coalition, the Neighborhood Power movement.

As the song goes, that was another place and another time. The institute eventually moved in another direction, and so did a great deal of the libertarian world. But Raskin's old writing deserves an audience today. Living under another corrupt president who has alienated some-but-not-all of the Washington establishment, I can't help thinking of one more passage in Notes on the Old System:

Even now, there are those in the media who will say that the System successfully worked its will in the Watergate/Nixon affair, and there are those in the bureaucracy and the banks, the corporations and the military, who will bathe themselves in self-congratulation because Nixon's excesses were condemned. They will say the national security groups, the CIA, the Department of Defense, and the policing agencies—the established power in the bureaucracy and among the elites—"blew the whistle" on Nixon just as they had done with Joe McCarthy.

We will be taught to forget the integral involvement of Nixon, the barons, and the Democratic party in developing the structure in which these excesses occur.

In the wake of Watergate, he added, the architects of a disastrous war "have been able to catch their breath and come forward as men of gravitas and decency. That they did not have to make any sort of public penance for the war is a political and moral travesty." Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

He wanted society to challenge corporate capitalism and to assure minimum levels of well-being. But not necessarily through the federal government.

Well then I just don't know how else he expected to do that. I mean, not even a nudge?

Same thoughts here. No matter how principled he seems compared to most Progressives, he still doesn't seem to understand that government means coercion to the point of death if necessary, and all the ancillary petty coercion that goes along with the grand rules, and all the corruption that follows.

Corporate capitalism is largely supported by federal tax structures and the regulatory apparatus.

Maybe thru state or local gov'ts.

Or gangs in the streets.

That all seems to have worked out for the best, though.

BEST SYST*M EVAH!

Sounds like a man of more principle than most.

Speaking of principles and principals, I often wonder what the founding fathers would think of the evolution of disrespect for the Constitution. I'd guess Hamilton and his ilk would be most approving, Jefferson and his ilk might be most disapproving, but how many would be swayed by arguments about much more complicated technology has made things? Would any think we had not gone too far? I find it hard to believe any would think we have not gone far enough in re-interpreting the Constitution, especially hypocrisies like needing an amendment to ban alcohol but not drugs.

And I wonder how many would have regrets about not solving the slavery question at the founding instead of letting it fester. I can understand the expectation that slavery would wither on its own, because that's where it was headed before the cotton gin.

how many would be swayed by arguments about much more complicated technology has made things?

Some, no doubt. Hard to estimate the total number. The 2nd Amendment may have been written more specifically with the advent and understanding of nuclear devices and seeing the progressives yell "you only have a right to black-powder muskets!"

Would any think we had not gone too far? I find it hard to believe any would think we have not gone far enough in re-interpreting the Constitution, especially hypocrisies like needing an amendment to ban alcohol but not drugs.

Surely. Especially things like the complete abuse of the Commerce Clause.

And I wonder how many would have regrets about not solving the slavery question at the founding instead of letting it fester.

Most. Especially in light of the 14th & 15th Amendments. None of the FF would have supported giving the Negroes the right to vote, especially not at the Federal level. And the concept of "anchor babies" would horrify them.

And the concept of "anchor babies" would horrify them.

You think? It seems to me that they knew that immigrants were needed at that point and had no problem with their descendants who were born in the US being citizens.

Yes. Because they didn't consider just anyone who got off the boat--let alone their kids--a citizen. The law was Jus Sanguinis.

They would have been appalled at this. Especially at the "bring in all the brown people you can" policy today. One of the first 10 acts of the first Congress was to limit citizenship to free whites only. Many of the FF made their views on this public, and it was non-controversial in their time.

Eg:

Jefferson thought the races should not be allowed to intermix, and that they could not function within the same government.

Madison wanted to purchase all the slaves and deport every one. He actually served as President of the American Colonization Society.

James Monroe worked so diligently to move blacks from the US to Africa that the capital of Liberia is named after him.

Right. Just because the founders were trying to establish the parameters of a nation where individualism could flourish didn't mean they didn't have some pretty shitty anti-individualistic notions of their own.

Well, they had different views than you. We can argue about whether they are shitty, or completely unfounded, or if there is some value to them, but their views are not your views.

So my point remains, which was that the Founders would have been opposed to the granting of Citizenship to blacks, and to elevating them to equals, and granting them the right to vote; let alone to say of giving a permanent offer of citizenship to every Mexican who can make it across the border just in time to have a baby.

You can hate them for this. You can disagree. But let's not rewrite history to pretend that they would agree with these "modern" policies.

"Jefferson thought the races should not be allowed to intermix"

k

Come on, that line was funny as hell.

That's the reality of the Founders. They were men, not saints.

Think of it what you will.

The Constitution is just a piece of paper. It's the ideas behind it that count. We NEED that piece of paper, of course, but without the ideas behind it, it's just a set of rules. What we need to restore are the ideas behind it. The ideas that the federal government has limited powers, is limited in scope, is structured to provide checks and balances upon itself, the division of powers between the federal government, the states, and the people, etc.

Let's get back to that before we start genuflecting to a bit of parchment.

I thought it was a piece of parchment.

Parchment, vellum, papyrus, birchbark, paper, whatever.

Progressivism and liberalism are two entirely different words, referring to two entirely different ideologies and world views. While they may superficially seem the same to the Know Nothings on the right, they are distinct. Liberals are about individualism, while progressives see only groups. Raskin appears to have been a liberal, not a progressive. Unfortunately, the last remnants of liberalism on the left was taken outside and shot during the 80s, just as the last remnants of conservatism were shoved through the woodchipper in the 90s.

Thank goodness for the first time in decades we have a president making a concerted effort to take power away from the evil administrative state in Washington, D.C. and put more money and power back in the hands of the people.

Let's continue draining the swamp in 2018.

"liberals provided the music for the corporations and asserted the need for a strong national leader who would operate benevolently through rhetoric and the bureaucracy for the common good of the System. His powers would verge on the dictatorial."

This quote is worth the price of the book right there.

Can't find my copy right now, but I recall Murray Rothbard saying favorable things about Raskin in "For a New Liberty," which was widely read and admired by libertarians back in the day.