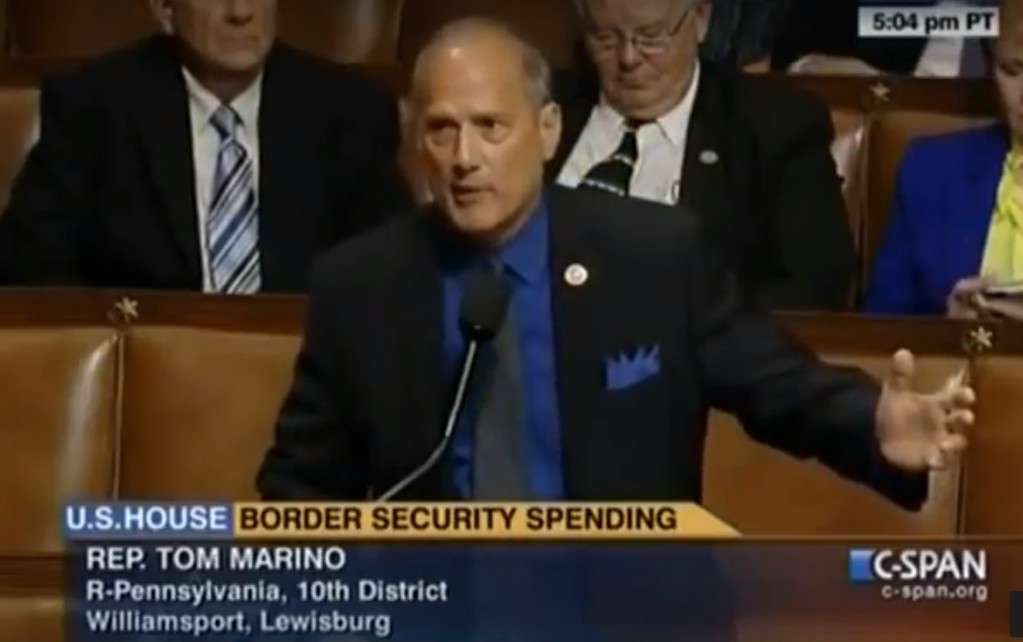

The Simpleminded Opioid Narrative That Doomed Tom Marino

The drug czar nominee withdrew his name after being portrayed as the henchman of villains who profit from addiction.

Today Tom Marino, the Pennsylvania congressman whom Donald Trump nominated to head the Office of National Drug Control Policy, withdrew his name because of a bill he was publicly bragging about just a year and a half ago. That bill, the Ensuring Patient Access and Effective Drug Enforcement Act of 2016, was uncontroversial when it was enacted. Not a single member of Congress opposed it. Neither did the Justice Department, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), or President Obama, who signed it into law on April 19, 2016. Yet Marino's sponsorship of the bill killed his nomination because of the way the law was framed in reports by 60 Minutes and The Washington Post.

According to those reports, which were the product of a joint investigation, Marino was doing the bidding of the pharmaceutical industry, and everyone else involved in enacting his bill was either bought off, duped, or steamrollered. But that portrayal is persuasive only if you follow the lead of 60 Minutes and the Post by uncritically adopting the perspective of a hardline DEA faction that was unhappy with the bill.

"In April 2016, at the height of the deadliest drug epidemic in U.S. history, Congress effectively stripped the Drug Enforcement Administration of its most potent weapon against large drug companies suspected of spilling prescription narcotics onto the nation's streets," the Post reports. "In the midst of the worst drug epidemic in American history," says 60 Minutes, "the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration's ability to keep addictive opioids off U.S. streets was derailed."

The provision highlighted by both reports limited the DEA's power to immediately suspend the registrations of manufacturers, distributors, pharmacists, and doctors based on an "imminent danger to the public health or safety." Marino's bill defined that phrase to mean "a substantial likelihood of an immediate threat that death, serious bodily harm, or abuse of a controlled substance will occur in the absence of an immediate suspension of the registration." It thereby constrained the DEA's ability to summarily stop people from prescribing or supplying controlled substances, requiring some evidence of a genuine emergency.

To my mind, any limit on the DEA's power is welcome. The DEA, not surprisingly, tends to take a different view. But the DEA's leadership, which at the time was trying to promote a less antagonistic relationship with the pharmaceutical industry, signed off on the new language, as did the Justice Department. Legislators read the DEA's approval to mean there were no law enforcement objections to the bill, which explains why it passed Congress with no resistance. Even ardent prohibitionists thought the clarification of the "imminent danger" standard was fair and reasonable.

"We worked collaboratively with DEA and DOJ…and they contributed significantly to the language of the bill," a spokesman for Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) told the Post. "DEA had plenty of opportunities to stop the bill, and they did not do so." A spokesman for Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) likewise said the DEA never expressed any reservations, adding, "The fact that it passed the entire Senate without hearing any sort of communication that would have triggered concern of at least one senator doesn't really pass the smell test."

By contrast, the disgruntled drug warriors who were the main sources for the Post and 60 Minutes stories—most conspicuously, Joe Rannazzisi, who used to run the DEA's Office of Diversion Control—see the bill as a shameful surrender to the evil pharmaceutical companies that profit from opioid addiction. That is the view that the Post and 60 Minutes adopted, almost without qualification.

The reports give short shrift to the argument that the vague "imminent danger" standard was unfair and legally shaky, to the point that it threatened the viability of the DEA's cases. They pay no attention at all to the perspective of the bona fide pain patients who suffer when the government cracks down on opioids. There is not a whiff in either report of the ineluctable conflict between drug control and pain control, even though reconciling those irreconcilable goals was the main rationale for Marino's bill. Nor do the reports give any sense of the damage done by pushing addicts into the black market, where drugs are more variable and therefore more dangerous.

It does not matter much whether Marino or someone else becomes Trump's drug czar, a position with little real power that is useful mainly as an indicator of an administration's drug policy inclinations. But it does matter that the simpleminded narrative endorsed by the Post and 60 Minutes, in which opioid addiction is caused by rapacious capitalists with the help of their paid stooges in Congress, is so widely and credulously accepted that Marino was doomed once it tainted him. That narrative leaves no room for the complicated sources of addiction (which is not caused simply by exposure to drugs), the ways in which prohibition makes addiction more perilous, or the harm that restricting access to opioids does to innocent bystanders.

Addendum: Yesterday Hatch, who sponsored the Ensuring Patient Access and Effective Drug Enforcement Act in the Senate, noted that Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.), who said Trump should withdraw Marino's nomination in light of the legislation, supported the bill at the time. So did Sen. Claire McCaskill (D-Mo.), who now says the law should be repealed. "Did the entire United States Congress decide to shield its eyes to the true sinister intent of this legislation?" Hatch asked in a floor speech.

While legislators' reluctance to read the bills they pass (even short bills like this one) should not be underestimated, they are on pretty shaky ground when they suddenly repudiate legislation they supported and portray sponsorship of it as disqualifying. Manchin and McCaskill are effectively saying they had no idea what they were voting for until they read about it in The Washington Post a year and a half later.

Show Comments (22)