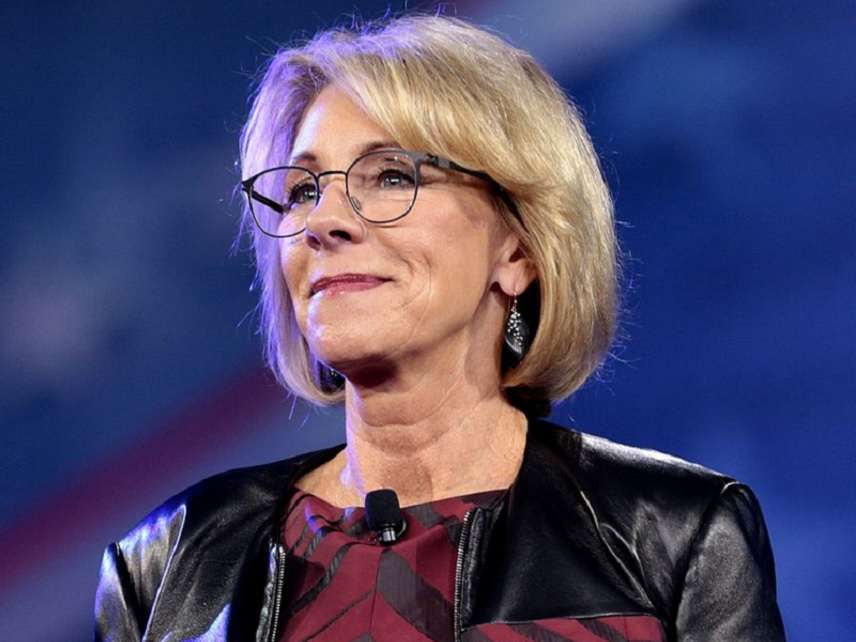

UPDATED: Betsy DeVos Isn't "Enabling Rape Deniers" by Pushing for Due Process on College Campuses

As Columbia University settles a case with a student found innocent of sexual assault, the Secretary of Education is rolling back a bad Obama-era policy.

Scroll to bottom for an update.

Have you heard that Education Secretary Betsy DeVos is "enabling rape deniers?" That's according to Jessica Valenti in The Guardian:

Campus rape victims have long been treated abysmally in the United States. They're often disbelieved by peers, administrators and school adjudicators, shamed by campus police, or watch as their attackers go unpunished.

Women tell stories of their accused rapists even academically flourishing as they themselves fail classes or drop out to avoid seeing their attacker. Under the Obama administration, that tide started to turn. We started to talk about Yes Means Yes initiatives and teach enthusiastic consent. There was a national conversation about how to best serve students who need our help.

We all know that the Trump administration and appointees are eager to undo Obama's work – but it shouldn't come at the expense of rape victims, and of justice.

That's not quite right.

DeVos is actually bringing something approaching due process back to college campuses. Specifically, she is working to roll back a bad Obama-era policy. In 2011, the Department of Education's Office of Civil Rights (OCR) sent out a "Dear Colleague" letter to colleges and universities urging them to adopt a new, lower standard of guilt when it came to adjudicating sexual assault and misconduct charges under Title IX, the federal law barring discrimination by sex in education.

At Reason, Cathy Young explained how the new standard worked in a particular case at the University of North Dakota:

[The student] was found guilty under a "preponderance of the evidence" standard of proof—the lowest standard, under which a defendant is guilty if the disciplinary panel believes it is even slightly more likely than not that he committed the offense. Traditionally, most colleges have adjudicated charges of misconduct against students under the higher standard of "clear and convincing evidence"—less stringent than "beyond a reasonable doubt," but nonetheless requiring an extremely strong probability of guilt.

A few months ago, the Office for Civil Rights of the Department of Education undertook to change that. On April 4, the OCR sent out a letter to colleges and universities on the proper handling of sexual assault and sexual harassment reports. One of its key recommendations was to adopt the "preponderance of the evidence" standard in judging such complaints.

The OCR's letter is not technically binding, but its recommendations have been implemented widely since public and private colleges that receive federal funds (read: all of them) are afraid that their support might be yanked. The result has been an explosion in the number of stories in which students, administrators, and faculty find themselves brought before a tribunal that not only requires a much-lower burden of proof than in a trial but routinely denies anything like due process and legal representation to the accused. In one emblematic and disturbing case, Northwestern Professor Laura Kipnis endured a bizarre on-campus Title IX hearing after publishing an article about her sexual exploits as a graduate student. A feminist and political progressive, Kipnis' experience led her to publish a book, Unwanted Advances, about how OCR's guidelines have given rise to what she calls "sexual paranoia" in higher education.

Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos is now calling for OCR to return "to its role as a neutral, impartial, investigative agency…[because it] had descended into a pattern of overreaching, of setting out to punish and embarrass institutions rather than work with them to correct civil rights violations and of ignoring public input prior to issuing new rules." That is, she will allow colleges to use a higher level of proof before finding someone guilty of a crime or offense. That's not "enabling" sexual predation or excusing misbehavior, it's making a flawed system better. There is no conflict between due process and treating victims of sexual assault with the care and consideration they deserve.

DeVos's change may also encourage colleges to avoid lawsuits like the one just settled by Columbia University. Paul Nungesser was accused of raping fellow student Emma Sulkowicz but cleared by all investigations. As a protest and officially approved art project, Sulkowicz carried the mattress upon which she claimed she was assaulted around campus for the remainder of her time at school (both she and Nungesser graduated in 2015). Nungesser ultimately sued Columbia for allowing and encouraging harassment of him after being found guilty (his lawyer told the Washington Examiner, "Columbia University, as an institution, was not only silent, but actively and knowingly supported attacks on Paul Nungesser, after having determined his innocence, legitimizing a fiction."). The terms of the settlment are private. Only in an atmosphere of "sexual paranoia," fueled in large part by the guidelines DeVos is rolling back, would a university have acted in such a way.

Earlier this year, I interviewed Laura Kipnis for Reason. Watch below and go here for a full transcript.

Update (3.30 P.M.): Ryan Compaan points me to this recent and excellent Chicago Tribune editorial about Betsy DeVos and the investigation of campus assaults. The piece discusses the "Dear Colleague" letter and its effects and closes with a sound policy prescription:

Civil authorities, who have no agenda to protect a school or to shortchange an alleged victim or perpetrator, still are best suited to mete out justice.

[C]ollege administrators [should] swiftly hand allegations of rape and other sex crimes to the people best qualified to deal with them — local cops and prosecutors.

We hope DeVos makes that a top priority. One option would be this rewrite of the 2011 letter:

Dear Colleague,

Someone reports a campus sexual assault? Call the cops.

Show Comments (61)