Sexual Paranoia Comes to Campus

Future generations will look back on the recent upheavals in sexual culture on American campuses and see officially sanctioned hysteria.

Future generations will look back on the recent upheavals in sexual culture on American campuses and see officially sanctioned hysteria. They'll wonder how supposedly rational people could have succumbed so easily to collective paranoia, just as we look back on previous such outbreaks (Salem, McCarthyism, the Satanic ritual abuse trials of the 1980s) with condescension and bemusement. They'll wonder how the federal government got into the moral panic business, tossing constitutional rights out the window in an ill-conceived effort to protect women from a rapidly growing catalogue of sexual bogeymen. They'll wonder why anyone would have described any of this as feminism when it's so blatantly paternalistic, or as "political correctness" when sexual paranoia doesn't have any predictable political valence. (Neither does sexual hypocrisy.) Restoring the most fettered versions of traditional femininity through the back door is backlash, not progress.

I didn't exactly mean to stumble into the middle of all this, and I hope that doesn't sound disingenuous. Sure, I like stirring up trouble—as a writer, that is—but I'm nobody's idea of an activist. Quite the reverse. Despite being a left-wing feminist, something in me hates a slogan, even well-intentioned ones like "rape culture." Worse, I tend to be ironic—I like irony; it helps you think because it gives you critical distance on a thing. Irony doesn't sit very well in the current climate, especially when it comes to irony about the current climate. Critical distance itself is out of fashion—not exactly a plus when it comes to intellectual life (or education itself). Feelings are what's in fashion.

I'm all for feelings. I'm a standard-issue female, after all. But this cult of feeling has an authoritarian underbelly: Feelings can't be questioned or probed, even while furnishing the rationale for sweeping new policies, which can't be questioned or probed either. The result is that higher education has been so radically transformed that the place is almost unrecognizable.

There are plenty of transformations I'd applaud: more diversity in enrollments and hiring; need-blind admissions; progress toward gender equity. But I dislike being told what I can and can't say.

When I first heard, in March 2015, that students at the university where I teach had staged a protest march over an essay I'd written about sexual paranoia in academe, and that they were carrying mattresses and pillows, I was a bit nonplussed. For one thing, mattresses had become a symbol of student-on-student sexual assault—a Columbia University student became known as "mattress girl" after spending a year dragging a mattress around campus in a performance art piece meant to protest the university's ruling in a sexual assault complaint she'd filed against a fellow student—whereas I'd been talking about the new consensual relations codes prohibiting professor-student dating.

I suppose I knew the essay would be controversial—the whole point of writing it was to say things I believed were true (and suspected a lot of other people thought were true), but weren't being said for fear of repercussions. Still, I'd been writing as a feminist. And I hadn't sexually assaulted anyone. The whole thing seemed incoherent.

According to our student newspaper, the mattress carriers on my campus were marching to the university president's office with a petition demanding "a swift, official condemnation" of my article. One student said she'd had a "very visceral reaction" to it; another called it "terrifying." I'd argued that the new codes infantilized students and ramped up the climate of accusation, while vastly increasing the power of university administrators over all our lives, and here were students demanding to be protected by university higher-ups from the affront of someone's ideas—which seemed to prove my point.

The president announced that he'd consider the petition.

Maybe it was shortsighted, but I hadn't actually thought about students reading the essay when I wrote it—who knew students read The Chronicle of Higher Education? I'd thought I was writing for other professors and administrators. Despite the petition, I assumed that academic freedom would prevail—for one thing, I'm tenured (thank god) at a research university. Also, I sensed the students weren't going to come off well in the court of public opinion, which proved to be the case. Marching against a published article wasn't a good optic—it smacked of book burning, something Americans generally oppose, while conveniently illustrating my observation in the essay that students' assertions of vulnerability have been getting awfully aggressive in the past few years. Indeed, I was getting a lot of love on social media from all ends of the political spectrum, though one of the anti-PC brigade did email to tell me that, as a leftist, I should realize that these students were my own evil spawn. I was spending more time online than I should have—though, in fact, social media was my only source of information about the controversy: No one from the university had thought to let me know I was being marched on. (I wasn't teaching that quarter and was trying not to be around much.) I first learned about the events on campus from a journalist in New York.

Let me be the first to admit that being protested has its gratifying side: When the story started getting national coverage, I soon realized my writer friends were all jealous that I'd gotten marched on and they hadn't. I began shamelessly dropping it into conversation whenever possible—"Oh, students are marching against this thing I wrote," I'd grimace, in response to anyone's "How are you?" I briefly fantasized about running for the board of PEN, the international writers' organization devoted to protecting free expression.

Things seemed less amusing when I got an email from the university's Title IX coordinator informing me that two graduate students had filed Title IX complaints against me on the basis of the essay and "subsequent public statements"—this turned out to be a tweet—and that the university had retained a team of outside investigators to handle the case.

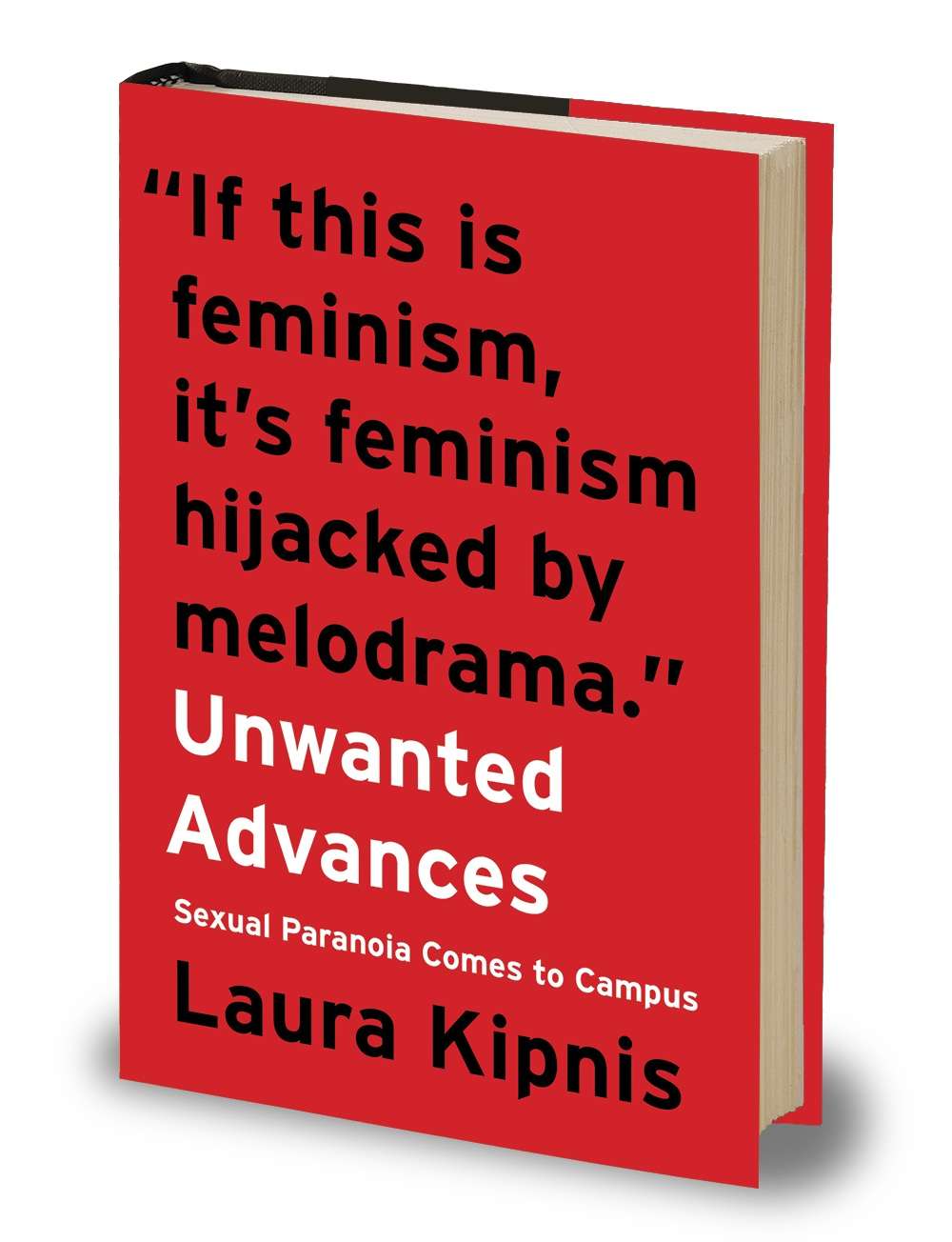

This article is adapted from Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to Campus, available now from HarperCollins.

Show Comments (143)