New York City's Slowly Sinking Pensions Are Taking on More Water

Just because you haven't heard about New York City's pension problems doesn't mean they don't exist.

Unlike places like Chicago, Dallas, and Detroit, where public employee retirement costs have become a full-blown crisis, New York City's pension troubles have stayed out of the headlines and have not generated much talk of bankruptcy.

Don't be fooled. The lack of national attention on New York City's public retirement plans has more to do with the seriousness of the crisis in other places than with anything New York has done. It's true the Big Apple is not teetering on the brink of financial collapse in the same way that the Windy City is, but pension costs are gobbling up a growing portion of New York's budget to levels not seen since the city's financial crisis of the 1970s, raising concerns about the long-term health of the city's retirement plans.

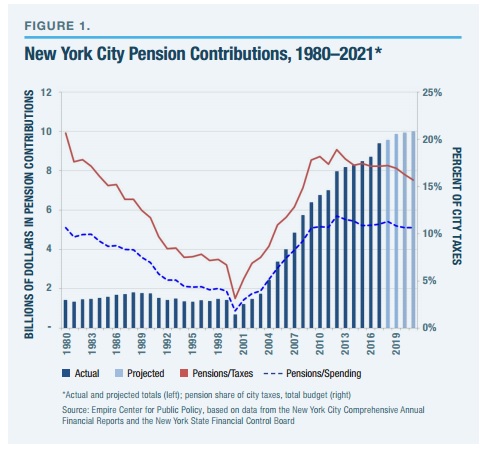

Annual pension contributions consume 17 percent of New York City's annual tax revenues and are increasingly crowding out other budgetary priorities, according to a new report authored by E.J. McMahon and Josh McGee, a pair of research fellows at the Manhattan Institute, a free market think tank. Within the next two years, McMahon and McGee warn, retirement costs will surpass social program spending as the second largest part of the city's budget, behind only education costs.

"In other words, the city has been spending more to meet its pension obligations than to build and renovate bridges, parks, schools, and other public assets," they write. "New Yorkers have forgone billions of dollars a year in services, infrastructure improvements, and potential tax savings to back up the state's constitutional guarantee of generous pensions for city employees."

New York's five pension funds are a combined $64.8 billion in debt, according to the city's official numbers, which assumes that the funds will earn annual investment returns of at least 7 percent in perpetuity. Using a more realistic expectations for future investment return (3.61 percent), the Manhattan Institute report calculates that the city's long-term pension debt exceeds $142 billion.

In the short-term, annual pension costs are hitting levels not seen since New York's economic crisis in the late 1970s. Mayor Bill de Blasio's $84.9 billion budget plan for 2018 includes $9.6 billion in payments to the city's five pension funds.

As the chart shows, pension costs have been rising steadily since the recession of 2001, from which the city's various retirement plans have never fully recovered. That downturn came close on the heels of policy changes made at the state level in 2000—at the urging of public sector unions—that enhanced retirement benefits and added $13 billion to New York City's pension liabilities over the first decade of the 2000s, according to a city comptroller report from 2011.

Among the ill-advised changes made in the early 2000s was a new rule that exempted most city employees from having to contribute towards their retirement. That's something that should change, McMahon and McGee argue, before taxpayers are asked to contribute more, and before the pension hole gets deeper.

Show Comments (32)