Congress Could Make It Harder for Local Pols to Blow Your Money on Stadiums

Bipartisan proposal would prohibit the use of tax exempt municipal bonds for stadium projects. That won't end stadium giveaways, but might reduce them.

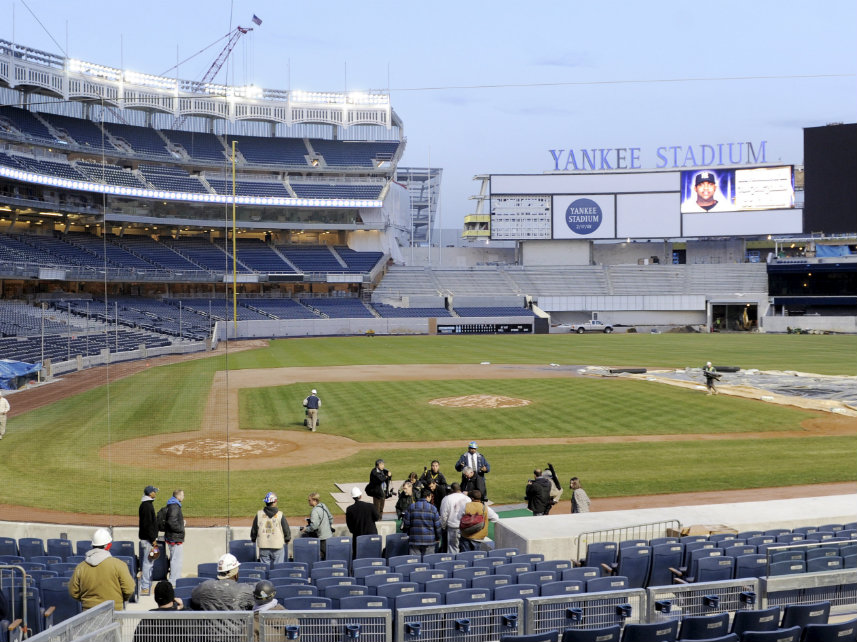

When New York City agreed to build a new stadium for the most valuable baseball team in the country, the Yankees, they partially paid for the project by issuing more than $1.6 billion in municipal bonds.

That means Red Sox fans in Boston ended up indirectly helping to build their rivals' new home.

A bipartisan bill introduced this week in Congress proposes to close the federal tax loophole that made that possible. The bill, sponsored by Sens. Cory Booker (D–N.J.) and James Lankford (R–Okla.), would not be the end of government-subsidized stadiums, but it would stop local officials from shoveling part of the cost onto the backs of taxpayers well outside their own jurisdictions.

The $1.6 billion in municipal bonds issued for the construction of the new Yankee Stadium is a record. But New York isn't the only city to take advantage of a loophole that ropes taxpayers from all across America into subsidizing stadiums. According to a recent analysis by the Brookings Institution, a centrist think tank, since 2000, 45 major professional sports stadium projects have been financed in part by more than $13 billion in municipal bonds.

Those bonds are meant to be used to pay for roads, sewer systems, schools, and other municipal infrastructure needs. They are exempt from federal taxes as a way of encouraging investors to buy them at lower interest rates, saving cities money. Those $13 billion in untaxed bonds for stadium projects have reduced federal tax revenue by $3.2 billion since 2000, according to the Brookings' estimate.

"It's an unseen subsidy," Victor Matheson, a sports economist at the College of the Holy Cross, told Reason on Wednesday. "It's a tax break that we never get to vote on, and it's one that don't even think about and don't see."

The bill introduced by Booker and Lankford would end the federal tax exemption for municipal bonds issued for stadium projects. Bonds issued to pay for infrastructure and other public projects would still be sheltered from taxation.

"It's not fair to finance these expensive projects on the backs of taxpayers, especially when wealthy teams end up reaping most of the benefits," said Booker in a statement. He pointed to the fact that decades of economic research shows little or no correlation between stadium projects and overall economic growth.

On that point, Booker is correct. The last three decades have been a sprawling cross-country experiment in the grand promises of economic growth spurred by building stadiums. The reality is you can build it, but the promised payoff rarely comes.

The Yankees got $492 million through the backdoor subsidy created by the federal tax exemption for municipal bonds, the Brookings study says. The New York Mets scored the second largest subsidy from taxpayers, $214 million for the construction of Citi Field, which opened in 2009 at a cost $815 million, more than $600 million of that funded by the public.

"Using billions of federal taxpayer dollars for the subsidization of private stadiums when we have real infrastructure needs in our country is not a good way to prioritize a limited amount of funds," said Lankford. "Everyone likes free federal money to build their expensive stadiums, but with $20 trillion in federal debt, this is waste that needs to be eliminated."

President Barack Obama proposed eliminating tax exemptions for municipal bonds attached to stadium projects as part of his 2015 budget plan, but Congress didn't bite. There are plenty of reasons to be skeptical that Booker's and Lankford's proposal will get through the legislative process—sports teams and wealthy bond-buyers are likely to lobby against it—but bipartisan support is a step in the right direction.

Even if the bill does pass, though, it won't be the end of subsides for sports stadiums. It will just make it more expensive for cities to hand-over millions of taxpayer dollars to billionaire team owners. Matheson estimates that ending the tax exemption on municipal bonds will make stadium projects between 20 and 33 percent more expensive, since cities would not be allowed to offer bonds with a tax-free interest rate.

They might just find other ways to swindle taxpayers, though. As Patrick Hruby of Vice Sports points out, the very loophole that Booker and Lankford are now trying to close was inadvertently opened in the 1980s when Congress voted to close a previous loophole for federal tax-exempt private revenue bonds that had been used to fund stadium projects. Local governments simply turned to tax-exempt municipal bonds.

Ending unnecessary and counterproductive subsidies for stadiums will require more than an act of Congress. It will require local (and sometimes state) officials who make these deals with teams find the fortitude to say "no," even when the teams threaten to pick up and leave.

City officials in San Diego and Oakland rebuffed efforts by their professional sports teams. Officials in St. Louis did the same, causing the Rams of the National Football League to skip to Los Angeles and and its new taxpayer-funded stadium.

Booker and Lankford admit their proposal isn't a complete solution. As a trade-off for closing the bond loophole, the senators' proposal would change other federal laws to allow local governments to finance stadiums by levying new taxes on in-stadium purchases—things like food, drinks, and team memorabilia.

But soaking people who choose to patronize stadiums is better than getting taxpayers in Wyoming to pay for a new stadium in Florida, something that's happening now, thanks to more than $490 million in municipal bonds issued to cover the cost of the Miami Marlins' garbage stadium.

This piece has been updated to correct the spelling of Sen. Cory Booker's name

Show Comments (33)