SCOTUS Rejects Deportation of Immigrant Who Had Sex With His 16-Year-Old Girlfriend When He Was 20

The decision highlights the importance of drawing distinctions among "sex crimes."

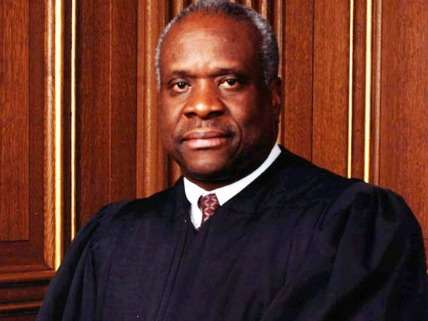

This week the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that a lawful permanent resident cannot be deported merely for having consensual sex with his girlfriend when he was 20 and she was 16. The opinion, written by Justice Clarence Thomas and joined by all of his colleagues except for Neil Gorsuch, who did not participate in the case, hinges on statutory interpretation but implicitly recognizes the danger of lumping all "sex crimes" together in an undifferentiated mass.

The case, which Lenore Skenazy covered here in February, involves Juan Esquivel-Quintana, who in 2000 emigrated with his parents from Mexico to Sacramento, California. In 2009 he pleaded no contest to "unlawful sexual intercourse with a minor who is more than three years younger than the perpetrator." California's law defines a minor as anyone younger than 18 and says violations can be treated as misdemeanors or felonies.

Esquivel-Quintana's sentence—90 days in jail, plus five years of probation—suggests the judge did not view his behavior as particularly heinous, and it would not even have qualified as a crime in most states. Thirty-one states and the District of Columbia currently set the age of consent at 16, while several other states have close-in-age exceptions that would cover a difference of four years. The Department of Homeland Security nevertheless argued that Esquivel-Quintana's intimacy with his girlfriend qualified as an "aggravated felony"—specifically, "sexual abuse of a minor"—under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), making him subject to deportation. An immigration judge and the Board of Immigration Appeals agreed, and a federal appeals court deferred to their interpretation of the statute.

The Supreme Court overturned those decisions. "Absent some special relationship of trust," Thomas writes, "consensual sexual conduct involving a younger partner who is at least 16 years of age does not qualify as sexual abuse of a minor under the INA, regardless of the age differential between the two participants." When Congress added that offense to the INA in 1996, Thomas notes, the age of consent was 16 or younger in 34 states and the District of Columbia. "Reliable dictionaries provide evidence that the 'generic' age—in 1996 and today—is 16," he says. Adding to that impression, a federal law dealing with "sexual abuse of a minor or ward," enacted in 1986 and amended in 1996, explicitly applies only when the victim is younger than 16. Thomas notes that Congress updated that statute "in the same omnibus law that added sexual abuse of a minor to the INA, which suggests that Congress understood that phrase to cover victims under age 16."

More generally, Thomas notes that the INA describes sexual abuse of a minor as an "aggravated" felony and lists it in the same subparagraph as murder and rape. "The structure of the INA therefore suggests that sexual abuse of a minor encompasses only especially egregious felonies," he writes.

The government argued that its interpretation of the INA should receive deference under the Chevron doctrine, which gives executive agencies broad discretion to decide the meaning of ambiguous statutes. Esquivel-Quintana's lawyers, by contrast, said any ambiguity should be resolved to his benefit under the rule of lenity, which favors the defendant when the meaning of a criminal law is unclear. The Supreme Court says neither argument is apposite, since the law is not really ambiguous. "We have no need to resolve whether the rule of lenity or Chevron receives priority in this case," Thomas writes, "because the statute, read in context, unambiguously forecloses the Board's interpretation."

Strictly speaking, this decision hinges on figuring out what the law says. Had Congress wanted to make actions like Esquivel-Quintana's deportable offenses, it could have done so explicitly, and in that case he would have had no grounds to argue that he was not covered by the relevant provision of the INA. But the ruling also highlights the arbitrariness of statutory rape laws, which in some states criminalize conduct that is perfectly legal in others, and the importance of drawing distinctions among so-called sex crimes. By acknowledging that only some offenses in that category can reasonably be described as "especially egregious felonies," the Court strikes a blow for rationality and proportionality in an area of the law dominated by hysteria and senseless severity.

Show Comments (15)