Howard Dean Says Ann Coulter Can Be Censored Because Them's Fightin' Words

The former DNC chairman's First Amendment analysis is spectacularly wrong.

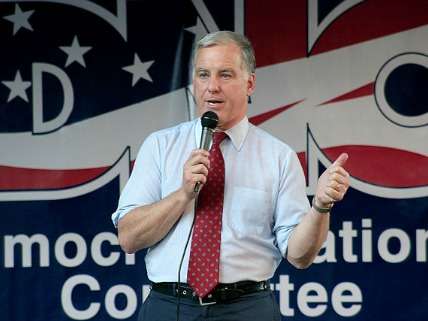

Howard Dean, former governor of Vermont, former presidential candidate, and former chairman of the Democratic National Committee, is a doctor, not a lawyer. Still, you'd think that someone who majored in political science at Yale and has been involved in politics for nearly four decades would know better than to declare, as Dean did last week, that "hate speech is not protected by the First Amendment." But instead of admitting his error, Dean is pushing a new claim in support of his argument that there was nothing constitutionally problematic about the University of California at Berkeley's decision to cancel a speech by conservative commentator Ann Coulter. Yesterday on Twitter, Dean claimed Coulter-style rhetoric "is NOT protected speech under the first amendment" because it amounts to "fighting words." He is wrong again.

This is NOT protected speech under the first amendment. Check Chaplinsky V New Hampshire SCOTUS 1942. https://t.co/wr3rMaRnAB

— Howard Dean (@GovHowardDean) April 23, 2017

Dean deserves some credit for referring to an actual First Amendment doctrine this time, as opposed to the entirely fictitious idea that "hate speech" is a constitutionally relevant category. The 1942 case he cites, Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, involved Walter Chaplinsky, a Jehovah's Witness who attracted a hostile crowd by denouncing organized religion as a "racket" on the streets of Rochester, New Hampshire. Chaplinsky was arrested for calling a city marshal "a goddamned racketeer" and "a damned fascist."

Chaplinksy's insults violated a New Hampshire law that made it a crime to "address any offensive, derisive or annoying word to any other person who is lawfully in any street or other public place," to "call him by any offensive or derisive name," or to "make any noise or exclamation in his presence and hearing with intent to deride, offend or annoy him." The New Hampshire Supreme Court had interpreted that law as applying only to words that "have a direct tendency to cause acts of violence by the person to whom, individually, the remark is addressed." Relying on that understanding of the law, the U.S. Supreme Court concluded that Chaplinsky's conviction did not violate the First Amendment because the epithets he used were words that "by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace."

Since the Supreme Court has repeatedly narrowed the "fighting words" exception to the First Amendment and has never again relied on it to uphold speech restrictions, the doctrine's continuing relevance is doubtful. In any case, the Coulter quotations cited by Dean clearly do not qualify as fighting words. Dean was initially outraged by a joke Coulter made in 2002: "My only regret with Timothy McVeigh is he did not go to the New York Times building." Yesterday Dean cited a 2016 Coulter tweet: "I would like to see a little more violence from the innocent Trump supporters set upon by violent leftist hoodlums." Neither of those comments remotely resembles fighting words as defined by the Supreme Court, which are insults directed at particular individuals in their presence that are apt to provoke a violent response from them.

Coulter: I'd like to see 'a little more violence' from Trump supporters https://t.co/e1uCaSQHPe

— Howard Dean (@GovHowardDean) April 23, 2017

Dean may be confusing fighting words with incitement. He seems to be implying that Coulter's comments might encourage violence not against her (as with fighting words) but against third parties (The New York Times in one case, anti-Trump protesters in the other). If that is what Dean means, he is still wrong to think the possibility of such violence means Coulter's statements are "NOT protected speech under the first amendment." In the 1969 case Brandenburg v. Ohio, which involved a Klansman arrested for advocating violence in the service of a political cause, the Supreme Court said such speech is protected by the First Amendment unless it is aimed at inciting "imminent lawless action" and is likely to have that effect. Neither Coulter's Timothy McVeigh joke nor her comment about violence by Trump supporters fits that description.

Since calling Coulter's remarks hate speech, fighting words, and incitement cannot justify suppressing them, Dean may be casting about for another excuse. Perhaps her comments qualify as "true threats," obscenity, or defamation. Although those arguments are absurd on their face, that does not mean Dean, desperate to defend censorship of someone whose speech offends him, won't try them out next.

Show Comments (66)