Scientists' March on Washington

Do researchers risk becoming just another leftwing interest group?

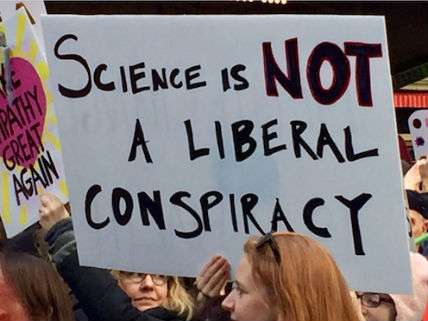

In the flush of excitement after the post-inaugural Women's March on Washington, someone in a Reddit conversation suggested, "There needs to be a Scientists' March on Washington." Sensing that a march on Washington might sound too aggressively partisan, the organizers have now renamed the event the March for Science. That march will take place tomorrow, on Earth Day, which the coordinators somehow figured would be the perfect nonpartisan date on which to muster tens of thousands of scientists and their comrades on the National Mall.

"We face a possible future where people not only ignore scientific evidence, but seek to eliminate it entirely," warns the march's mission statement. "Staying silent is a luxury that we can no longer afford. We must stand together and support science."

From whom do the marchers hope to defend science? Certainly not the American public: Most Americans are fairly strong supporters of the scientific enterprise. An October 2016 Pew Research Center poll reported, "Three-quarters of Americans (76%) have either a great deal (21%) or a fair amount of confidence (55%) in scientists, generally, to act in the public interest." The General Social Survey notes that public confidence in scientists stands out among the most stable of about 13 institutions rated in the GSS survey since the mid-1970s. (For what it's worth, the GSS reports only 8 percent of the public say that they have a great deal of confidence in the press, but at least that's higher than the 6 percent who say the same about Congress.)

The mission statement also declares, "The application of science to policy is not a partisan issue. Anti-science agendas and policies have been advanced by politicians on both sides of the aisle, and they harm everyone—without exception."

I thoroughly endorse that sentiment. But why didn't the scientific community march when the Obama administration blocked over-the-counter access to emergency contraception to women under age 17? Or dawdled for years over the approval of genetically enhanced salmon? Or tried to kill off the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste storage facility? Or halted the development of direct-to-consumer genetic testing?

One problem is that many of the marchers apparently believe that scientific evidence necessarily implies the adoption of certain policies. This ignores the always salient issue of trade-offs. For example, acknowledging that man-made global warming could become a significant problem does not mean that the only "scientific" policy response must be the immediate deployment of the current versions of solar and wind power.

The mission statement proclaims that the marchers "unite as a diverse, nonpartisan group to call for science that upholds the common good and for political leaders and policy makers to enact evidence based policies in the public interest." Setting aside the fact that the march was conceived in the immediate wake of the decidedly partisan and specifically anti-Trump Women's March on Washington, how credible are these claims to non-partisanship?

As it happens, I received an email on Thursday from the publicist for Shaughnessy Naughton, who is a chemist, a cancer researcher, and the founder of the activist group 314 Action. Naughton's group is one of the March's 170 partner organizations. 314 Action's political action committee is recruiting scientists, engineers, and other technologists to run for political office, and it plans to provide them with the "resources they need to become viable, credible, Democratic candidates." The publicist informed me that Naughton is "available to discuss this weekend's March for Science in Washington, D.C., which will assemble scientists from across the country to rally against the Trump 'war on science.'" The headline earlier this week in the reliably left-wing Guardian makes no bones about the intent of the marchers: "Science strikes back: anti-Trump march set to draw thousands to Washington."

The 170 partner organizations that have endorsed the march include such stalwart groups as the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists, and the New York Academy of Sciences. But the marchers have also accepted as partners a variety of left-tilting activist groups—not just 314 Action, but 350.org, the Center for Food Safety, the Center for Biological Diversity, and the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Microbiologist Alex Berezow is a senior fellow of biomedical science at a pro-science consumer advocacy organization, the American Council on Science and Health.* I asked him if he thought scientists should participate in the march. "No, scientists and researchers should not participate," he replied. "From the very outset, the march started as an anti-Trump protest. Then it morphed into a solidly progressive movement, embracing all manner of left-wing social justice causes." Berezow added that the march could well end up harming the interests of the scientific community: "For decades, science has received broad bipartisan support. (In fact, Republicans usually funded science better than Democrats.) By biting the hand that feeds them, scientists risk losing funding, as well as alienating taxpayers. That is an awful idea, and it hurts everybody."

I have considerable sympathy with the scientific community's worries about the Trump administration. Indeed, I gave Trump a mostly failing grade on science policy when he was running for president. But Berezow is all too right that the marchers risk turning the scientific enterprise into just another special interest group in the eyes of the public. If that happens, scientists might someday find themselves right down there in the bottom of the polls with the press and Congress.

*Disclosure: In 2008, I researched and wrote the report Scrutinizing Industry-Funded Science: The Crusade Against Conflicts of Interest on a contractual basis with the American Council on Science and Health for a fee of $4,000. The agreement specified that the report would be peer-reviewed, and I am grateful for many insightful comments from reviewers that I incorporated into the report.

Show Comments (255)